December 15, 2014, by Guest blog

Race and Rights: Ferguson Part 3

Post by James Brookes

Below is the third of a multi-part series responding to events in Ferguson – the protests and civil disorder that began the day after the fatal shooting of an African American man, Michael Brown, by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, and continued after the decision on November 24, 2014 by a grand jury not to indict the police officer. Nottingham’s Race and Rights cluster and postgraduate reading group, based in the Department of American and Canadian Studies, examine Ferguson through the lens of their research. In this third posting, James Brookes looks at Ferguson against a backdrop of violence and death in American visual culture.

The body of Michael Brown lay in the middle of Canfield Drive for approximately four hours in the midday heat of August, despite the fact only 90 seconds passed between Officer Wilson stopping the teenage boy and firing his last shot at him. During this period neighbours, friends and family of Brown witnessed his corpse, facedown, with blood streaming from his head out onto the street. The gruesome spectacle drew crowds of mortified and curious onlookers, including many children; leading to pleas from members of the public to have the body covered. The decomposition of a body begins as soon as the heart ceases to beat and within three to six hours a body may start to become rigid as rigor mortis occurs. It is incomprehensible as to why the St. Louis County Police Department allowed Brown’s body to lay unattended for such an extended period of time.

Jonathan Capehart, writing for the opinion page of the Washington Post, states that Brown’s body was entirely neglected: “No aid was administered… No ambulance was called.” In fact, homicide detectives were not even called to the scene until about 40 minutes after the shooting. It is true that the crowd of observers hindered the police investigation and that reported gunshots at the scene did little to allow forensic work to run efficiently. However, is it not evident that not shielding the body from the local community drew these crowds and caused tensions to rise at the scene? Drawn by the exhibition of death crowds of spectators formed requiring the police to mobilise canine units and SWAT teams. In comparison, New York Police Chief Gerald Nelson outlined his forces’ policy towards the deceased in Brooklyn: as soon as the victim is concluded dead “that body is immediately covered.” Patricia Bynes, a Ferguson committee-woman, explained a sinister motive for the lack of attention towards Brown’s body. She argued that the extended public display of the corpse sent a message from law authorities that “we can do this to you any day, any time, in broad daylight, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Kelly Christian has studied the visual culture of the Ferguson crisis and in this piece she claims Brown’s murder is “another page in the American history of racist systematic violence.” We see similar instances extend back to the Civil Rights movement, to the public lynchings held in the 1880-1930s, and further into the tumultuous years of Civil War and of course the systematic oppression of slavery. It was not long after Brown had his life taken that countless images and videos of his body flooded onto television screens, online news journals, and social media websites. As Christian notes, it was not uncommon for photographs of a lynched body in the early twentieth century to appear on postcards that would be circulated in order to illustrate the capabilities of whites and the African American male’s tenuous place in that community. The image of Brown’s body, facedown and disregarded in the street, serves as a visual reminder of the terrible injustices that can be committed by authorities towards minorities and the second-class treatment they often receive, even in death.

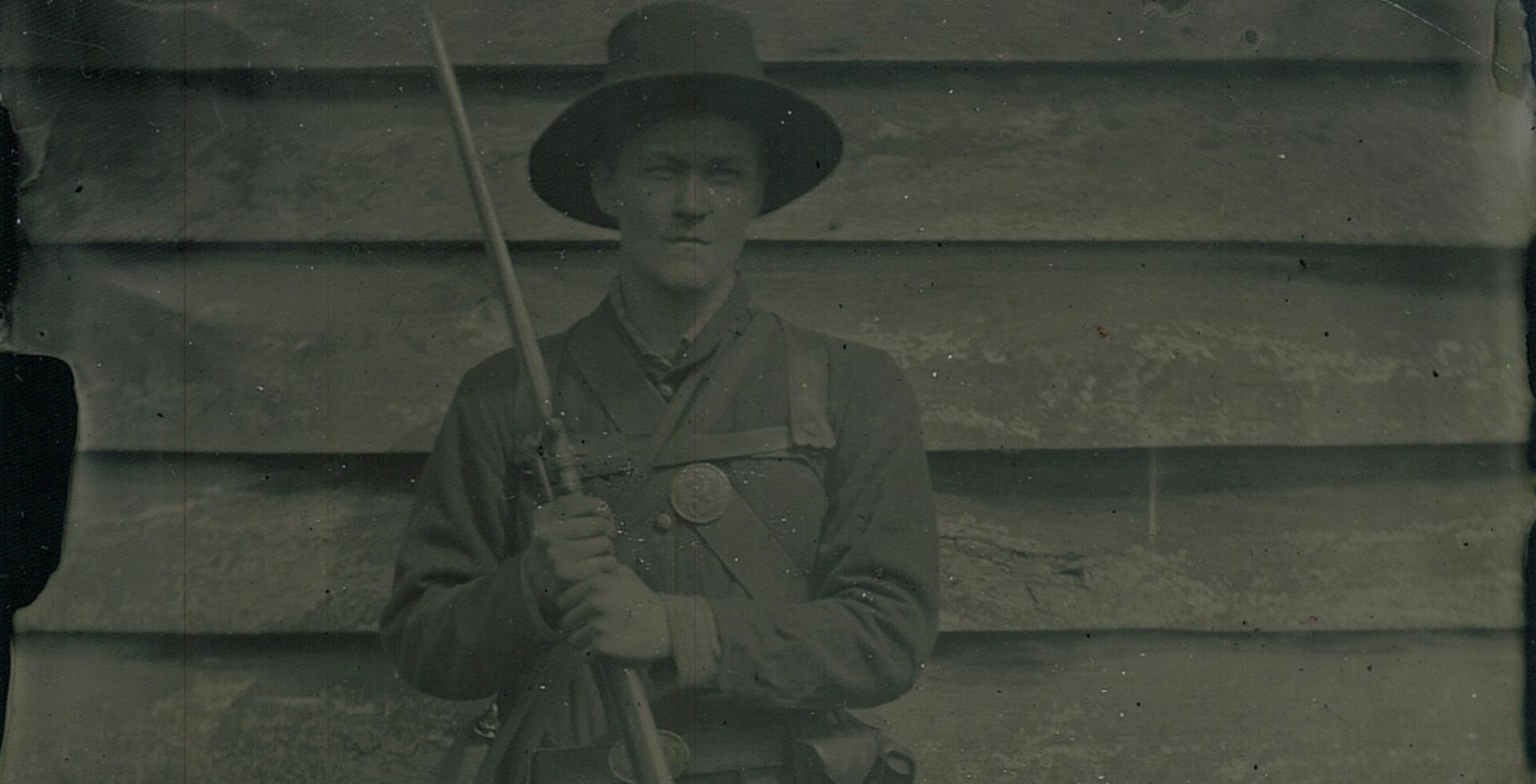

In my own current research, which focuses on the photographic portrait in relation to northern Civil War soldiers, both black and white, it has also been necessary to study and give attention to the range of images of the dead from that conflict. The British observer George Sala was moved to write of an image of a neglected corpse on a battlefield from ‘The Dead of Antietam’ exhibition: “This is what your civilisation has come to. A free government, religious toleration, universal education, wise laws, national wealth… and the result of all these wonderful engines of amelioration is a poor devil with a hole in his stomach and his entrails protruding… This is civilisation in warfare.” In an October, 1862 article, a New York Times reporter commenting on the same collection of images noted “If [Mr. Brady] has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.” These commentaries on the photography of dead bodies remain significant to this day, and surprisingly so in Michael Brown’s case. The far-reaching, influential media platforms of the present day allow Brown’s body to be transported from Canfield Drive in Ferguson and brought to homes of millions worldwide. Regardless of the purported benevolence, liberty, freedom and equality of the United States in the twenty-first century, the images of Brown’s body extinguish these notions of amelioration and force us to reconsider the true indicators of a nation’s civility.

James Brookes is an MRes student in the American and Canadian Studies department, where he is writing a dissertation on the visual culture of American Civil War soldiers. He is a member of the Race and Rights research cluster and PG reading group, and also regularly engages in public and living history events, including Civil War re-enactments and 19th-century wet-plate photography work.

Image: Tintype portrait of James Brookes portraying a member of the 19th Indiana in 1863 from a 2013 demonstration of 19th-century photography by historical photographer Alex Burnham.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply