August 7, 2013, by Malvika Johal

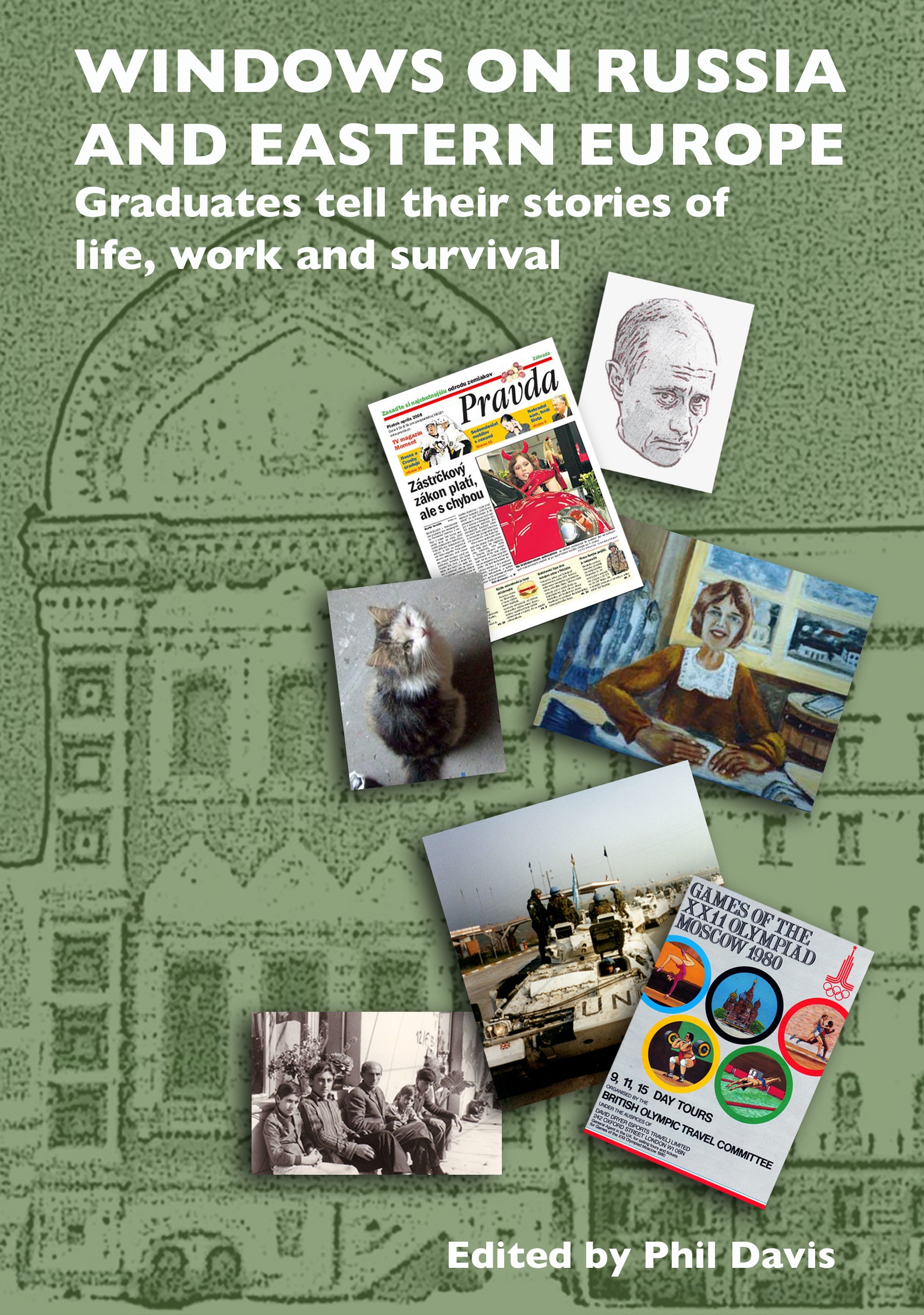

Windows on Russia and Eastern Europe

Windows is a collection of individuals’ tales of how the Communist-controlled lands of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe evolved from Stalinism to Gorbachev’s perestroika to the robber baron days of the 1990s and finally to today’s uneasy mix of free markets and semi-authoritarian rule. The stories are those of graduates of Slavonic studies, who chose to live and work in the former USSR and Communist Eastern Europe. Setting off on their chosen path in Slav lands, the authors were typically well-versed in terms of language and culture. But many underestimated the challenges – and dangers – they would encounter.

In our second sneak peek into this collection, Rod Thornton was part of a British army contingent sent to protect fuel supplies in Bosnia. Here he describes how his small band are given less than homely barracks.

We arrived at the Egyptian barracks in the middle of one of Sarajevo’s monumental dumps of snow. A sentry sent us round to the rear of the building. At the back there was a narrow (15m wide) vehicle parking area between the rear of the barracks and the mountainside. Having parked and debussed, we moved at pace – mortar rounds were falling in the vicinity – to gain entry via the back door.

We went inside and were made very welcome by an Egyptian officer. He gave us a tour of the building. The cookhouse was on the ground floor and all the troops slept in the basement. Down there in the boiler rooms, within the dark recesses and amid miles of pipes were set up hundreds of camp beds. It all looked deeply dingy and most uncomfortable. “Why are there so many beds down here?” we asked.

There were a couple of hundred of Egyptians in the building and they all seemed to be living in the basement. Why weren’t they spread out on the upper floors? “No”, said the officer, “because of the shelling we all live down here in the cellar where it is safe.”

“Okay. So where do we sleep, then?”

“On the top floor?”

“On the top floor?”

“Top floor, yes. That is the only spare rooms we have.”

It transpired that the rooms at the top of the building were spare because the Egyptians – in mortal dread of the shelling – never dared venture up there. All the rooms on the other floors below the fifth were taken up by storerooms or, below them, by offices.

“You will be most comfortable up there. Lots of space.”

An estate agent would have had a hard job selling this one as well. While we now had more air, we also had some very noisy neighbours. And although we had better views than before, we would rather not have been able to see, thank you very much, the shells and tracer bullets flying past the windows. However, the true negative for us was not so much being smack in the middle of war-zone central, but rather that we were such a long way from the ground. One of the most severe consequences of Sarajevo having no power was the fact that the lifts did not work. This meant that a fair proportion of the population, unable to climb flight upon flight of stairs within the innumerable blocks of flats, became housebound. And, if they became housebound, they could not go out to get water or food. Without help from neighbours, they could simply die.

We had much the same problem in the Egyptian barracks, although on a far less dramatic scale. While mobile generators kept the lights going, they could not provide enough power for the lifts. Thus all our kit had to be lugged to the top floor. This included weapons and ammunition, rations for several weeks (we dared not, despite the copious invites, eat in the Egyptians’ restaurant) and all our water. And you have simply no idea how much water the average human needs in any one day – and how much it all weighs. There is water for drinking, for cooking, for washing and for flushing the toilet. It all adds up. And it had all to be brought up five flights of stairs in jerricans.

Eventually, though, we were all set up and settled into our new residence. There was no glass in the windows – it had long since been blown out by blasts – and the window spaces were covered by clear plastic sheeting. This kept the wind out, but not the cold. There was absolutely no furniture in the room, but we had brought our camp beds and sleeping bags and we used unopened ration boxes to create tables and chairs. It was like a camping expedition. We would cook communal meals – using food from our ration packs – on gas burners set up in the middle of the room. The fire hazard seemed inconsequential given the hazards that existed outside. At night, after a day’s work, we would play board games and run card schools. We washed ourselves and our clothes when we could, but there was never any hot water. Even if someone did take the trouble to wash their nether garments in some chilly water, they would have to wait about a week before they would dry in the freezing room. Most of us had not had a shower since we had arrived in Bosnia some four months earlier and a flannel wash every now and again was the best that could be done. We all stank and we stank even more after three months in Sarajevo. But the fact that we were all equally malodorous meant that we didn’t smell bad to each other.

There was, though, an immense amount of shelling. When bored of an evening, you could just sit by the window and watch the tracer and the impacts of shells, mortar rounds and anti-aircraft and heavy machine-gun bullets. Bonfire night had nothing on this. In that winter of 1992-93, at the height of the shelling of Sarajevo, there was an average of 700-800 explosions recorded every day by the UN authorities; the vast majority of them in the hours of darkness and within a mile of our building. On some days there would be over a thousand blasts and I still have a UN Daily Log for one such day. The blast waves of some of the explosions would push in or even tear the plastic sheets that covered the windows and occasionally there would be a thunderous drum-roll as the roof was struck by pieces of shrapnel. Each explosion would be preceded by a flash of light – day or night. And, as with lightning, there would always be some sort of time difference between flash and bang. Sometimes, though, the flash and bang came almost together. When they did, the noise would be less of a sound and more of a feeling, a sensation. A jack-hammer thump that shook everything in the room and everything in your body. If you had your mouth closed at the time of the thump, the pressure on your ears was immense. Still, to this day, I cannot see a camera-flash go off without bracing myself and waiting for the bang. Some things never leave you.

For further information on “Windows” and to pre-order the book, contact publisher James Muckle at: bramcotepress@ilk81rr.orangehome.co.uk

Don’t miss out on the upcoming Russian and Slavonic Studies alumni event to celebrate the launch of this fascinating new book on Saturday 26 October.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply