September 22, 2016, by Stephen Legg

British Parliamentary Archives, London

The Parliamentary Archives house the records of the House of Lords, the House of Commons and other collections relating to the running of Parliament. Visits are by appointment only and the staff were kind enough to have ordered in-advance some documents I had located via the online database, Portcullis. These included personal papers (Correspondence between Davidson and Samuel Hoare), papers submitted in advance for use at the first Round Table Conference, bureaucratic materials relating to the opening ceremony and even the Dispatch Box used at the Conference by the Attorney General. The materials promise to give fascinating insights into the lobbying that took place across the three Round Table Conferences, between November 1930 and December 1932, as well as making clear the significance that was placed on the venue and setting. The opening ceremonies, in particular, clearly had to compare favourably to other international conferences that had taken place in London around that time, while the use of the House of Lords for the opening ceremony was felt by William Wedgwood Benn, the Secretary of State for India, to have had an indelible impact on the tone of proceedings.

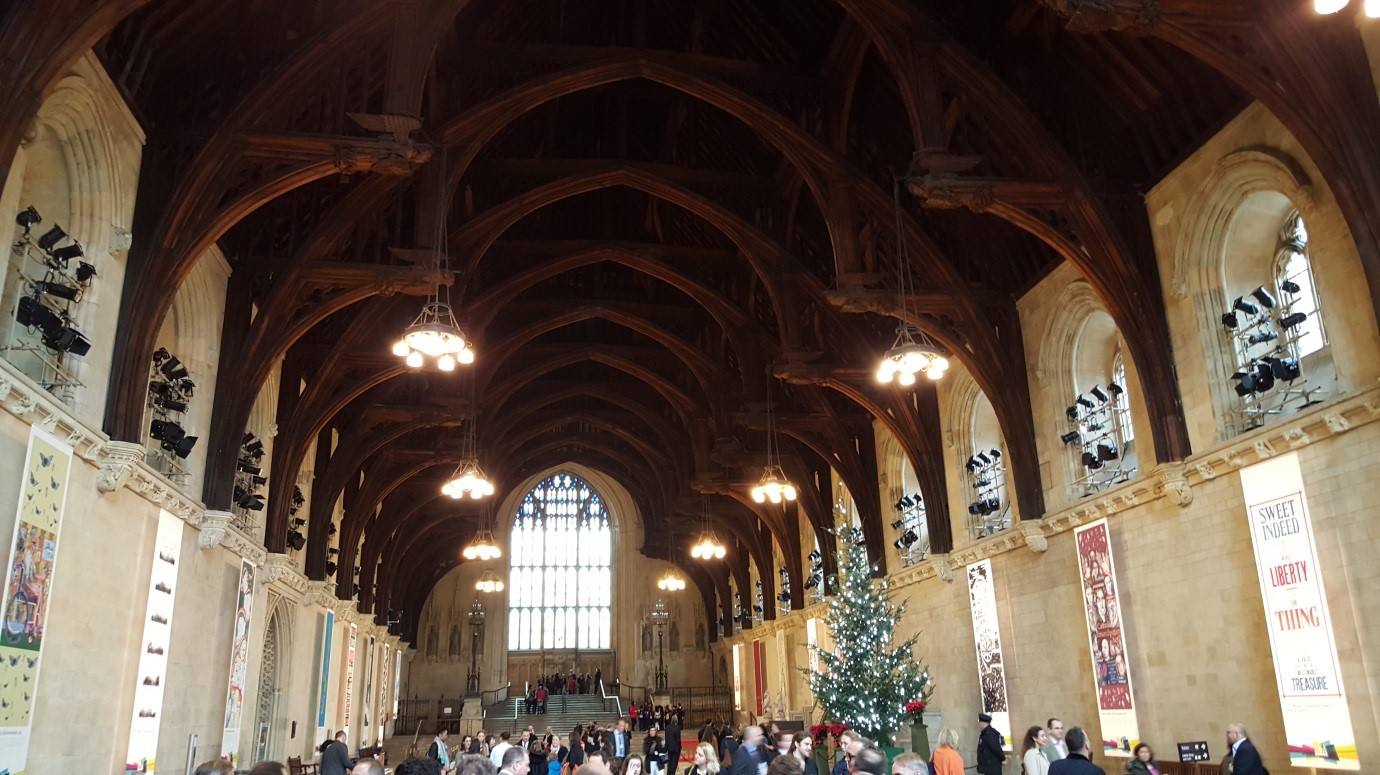

If the presence of India in these particular documents was obvious, the presence of Britain’s imperial past, and India’s role in it, was less obvious but certainly present in the location of the archive itself. To access the archives before 11am required the reader to use the Cromwell Green Visitor Entrance (passing through high level security and a whole other series of imperial [Irish] connotations) and to make oneself known to a Visitor Assistant in Westminster Hall. The oldest part of the Palace complex (completed in 1097), the hall is famous for its size and its still functional role as a site of government (on 8th December 2015, when visited, it contained an exhibition on liberty, multitudinous conference guests, and a Christmas tree).

But for those with an interest in Indian history it was also the site of one of the most pivotal turns in the history of the East India Company; the trial of Warren Hastings. As Parliament’s heritage website puts it, this was the longest trial in the Hall’s history, which had also included the trials of William Wallace, Thomas More, and Charles I: “The most notable 18th century trial was that of Warren Hastings in 1788[-1795]. It was in fact the longest in British history; it lasted seven years although the court only sat for 142 days. Hastings was accused of corruption during his years as Governor-General of Bengal, but was eventually found not guilty of all sixteen charges against him. By then, however, he was a ruined man. The trial acted as a warning to Hastings’ successors, and did much to make British rule in India a rule of law.” The trial was the subject of a book by the historical Nicholas Dirks The Scandal of Empire: India and the Creation of Imperial Britain and of several beautiful illustrations from the time.

A Visitor Assistant showed me to the archives but, on hearing that I was working on India, took me on a detour to the remarkable series of murals depicting historical scenes from the Stuart period. Nestled among these is a depiction of Sir Thomas Roe, envoy of James the First, being received at the court of the Mughal Emperor, Jahangir in 1614.

If this scene marked the fictive beginnings of formal contact between England and India (the latter being by far the stronger imperial power at the time) on exiting the building later in the day I was faced with two powerful monuments to powerful men who had helped craft the ending of the British Empire in India. Turning right from the Victoria Tower exit, across Abingdon Street, and behind some road works, I was confronted with the statue of King-Emperor George V.

He had visited Delhi for the Imperial Durbar of 1911 where he announced that the capital would be moved to that city from Calcutta and, nearly 20 years later, he inaugurated the first Round Table Conference on 12 November 1930. Turning to the left from parliament, however, brought me to Victoria Gardens and to the statue of MK/Mahatma Gandhi which had been unveiled, not without controversy, a year before.

“Gandhi statue unveiled in Parliament Square, with PM David Cameron praising ‘magnificent tribute to towering figure’”

Gandhi had been imprisoned for the first Round Table Conference but was freed to attend the second conference in 1931. The delegates were due to be welcomed by the King-Emperor in person but Gandhi’s refusal to wear much more than his loincloth posed a major breach of royal etiquette but the Palace relented. Asked later if he had been wearing enough clothing to meet the King, Gandhi supposedly replied “The King had enough on for both of us.”

So, from Sir Thomas Roe and Emperor Jahangir to Mahatma Gandhi and King-Emperor George V, within one corner of Westminster. The Round Table Conferences themselves, after the opening ceremony, actually took place in St James’s Palace, across the Park and down the Mall. The subject of a later entry….

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply