December 11, 2017, by Judith Jesch

Danelaw Saga: Bringing Vikings Back to the East Midlands

By Ursula Ackrill

The Weston Galley’s Danelaw Saga tells a new and exciting story with Viking finds borrowed from museums as well as with manuscript and printed exhibits sourced from Manuscripts and Special Collections at the University of Nottingham. The exhibition complements the current University of Nottingham Museum’s exhibition Viking: Rediscover the Legend by focusing on the East Midlands’ Viking settlement and connecting this to the Victorian rediscovery of the Old Norse cultural landscape. Danelaw Saga begins with an invasion evidenced by ordinary day-to-day objects that the Northmen carried to the East Midlands in their luggage and by alien artefacts encountered here by them such as the Repton warrior stone. The Anglo-Saxon population of the East Midlands lived alongside the Viking hamlets and villages which sprang up all over the Danelaw, where Viking laws and government reigned across five boroughs (Derby, Leicester, Lincoln, Nottingham and Stamford). This is evident because Old Norse words entered the Old English language and are still in common use today. Moreover, Viking place-names from the days of the Danelaw still adorn the map of the East Midlands. Medieval manuscripts and an online database of place-names reveal the Viking origins of many localities.

Invasion and settlement were followed by assimilation over centuries to the point where people of Viking descent became indistinguishable from the other inhabitants. The culture of the Vikings, however, made a comeback comparable to a second invasion. Thanks to the print revolution, interest in Old Norse language and literature took hold of the imagination of Scandinavian peoples and spread into Britain and continental Europe. Old Icelandic texts translated into modern languages played an important role in conceptualising national identities in northern Europe in the 19th century. One early example of Viking reinstatement in mainstream culture is documented in an exchange of ideas between the great German poet Friedrich Schiller and his translator Joseph Charles Mellish of Blyth which took place in Weimar in c.1800. Schiller actually encouraged Mellish to write an opera about King Alfred the Great’s strategic retreat and subsequent victory over the Danish king Guthrum. Later on Victorian authors William and Mary Howitt claimed that the British Empire’s global success was in fact a late flowering of the Vikings’ legacy, Britain having made the most of the social and entrepreneurial liberties imported by her invaders from a thousand years ago. A scramble for Scandinavian heritage ensued, particularly between Britain and Germany, but the Old Norse patrimony proved flexible enough to sustain different collective identities and outlooks over time. In the 20th century the local author Hilda Lewis charmed the readers of her 1939 children’s novel The Ship that Flew by updating the Viking war-ship for the age of automotive travel. Her ship functions like a hovercraft with an in-built time travel kit but draws its magic at the same time from legend, being a model ship of a Viking vessel.

In Danelaw Saga the story of Viking influence from settlement through to reimagined heritage comes full circle. This exhibition performs the latest reimagining by placing the Viking cultural strand back on foundations unearthed by archaeology and authenticated by scientific research.

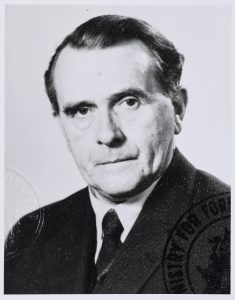

The printed materials in the exhibition are sourced mainly from the collection donated by the family of the Icelandic scholar and diplomat Eiríkur Benedikz to the University of Nottingham Eiríkur Benedikz Icelandic Collection, MS718/2/1

Friday 15 December 2017 – Sunday 8 April 2018

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply