March 13, 2017, by Words on Words

The Austen Debate

This blog post was written by second year English and Philosophy student, Ayisha Sharma.

Jane Austen, one of the first names that springs to mind when you think of English Literature, seems to attract polarised views. She’s either a timeless social satirist or the complete opposite; a writer very much of her time. While I wouldn’t consider myself a die-hard Austen fan, I do enjoy occasionally perusing the pages of Pride and Prejudice. So I thought I’d contribute a few of my thoughts to the debate.

Image: Wikimedia Commons (Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin.) / CC0 1.0

One supposedly alienating feature of Austen is that her protagonists fall into the niche category of middle-class women. Her plots are thus centred on the concerns of such women, whether they’re as major as making a suitable marriage or as minor as trimming hats. But considering Austen’s own position in the lower gentry, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. After all, isn’t writing about the issues closest to one a logical, and even wise, thing to do?

So maybe it’s not Austen’s content that’s at issue so much as her stylistic expression of it. An ironic omniscient narrator may indeed elicit the occasional chuckle from a reader but social issues, it can be argued, have been explored in much more imaginative ways.

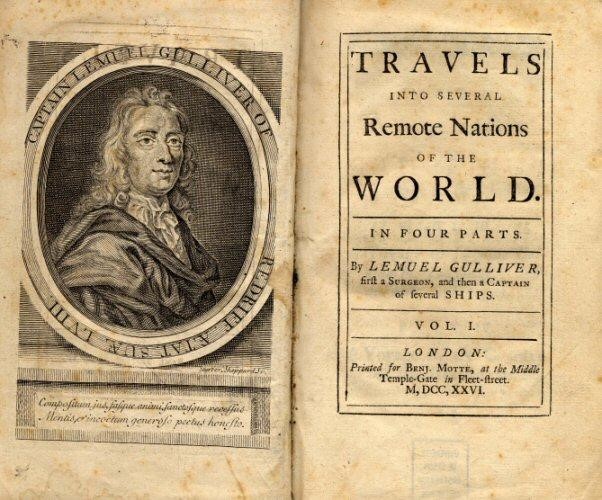

Think Swift’s fantastical world of Lilliput in Gulliver’s Travels or the quirky bathos of Pope’s The Rape of the Lock. These works possess an instant attraction that Austen seems to lack. But I think it’s commendable that Austen wrote about women in a fairly direct manner, omitting the glossy sheen of major stylistic experimentation. In doing so, she was able to focus better on the heart of the issue.

Image: Wikimedia Commons / CC0 1.0

Perhaps the most contentious question regarding Austen is whether her works continue to strike a chord with today’s readership; a readership in which women are no longer totally preoccupied with balls and bonnets and individualism is not as frowned upon. The immediate answer would be a resounding ‘no’.

It’s too difficult to see oneself in the naïvely romantic Marianne or the emotionally repressed Eleanor. And it’s too easy to be utterly confused by Catherine’s immersion in Gothic literature to the point that she wrongly cries murder.

But it’s not at all difficult to go wrong in an attempt to balance one’s emotion and reason, as the sisters of Sense and Sensibility do. And it’s easier still to immerse oneself in escapism to the point that the lines between appearance and reality become dangerously blurred, as Catherine finds in Northanger Abbey.

So if you’re at a loss for which book to dive into next, why not consider some Austen? You may find it an enriching and even pleasurable experience.

Ayisha Sharma

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply