April 27, 2016, by Words on Words

Lobsters, Regionalism, and Much More: T. S. Eliot and British Surrealism in the 1930s

This blog post was written by School of English PhD student, Xiaofan Xu.

At first glance, T. S. Eliot and surrealism just do not seem to click. Eliot is known to have rejected a manuscript on French surrealism in 1926 for publication in his Criterion, with a dismissive comment that ‘I cannot feel that the theories of the surréalistes are of sufficient importance to justify us in treating them with so much care’ [1]. However, the following decade seems to have witnessed a change in his attitude towards surrealism. He attended the London Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, and even before that, he had published a few distinctly surrealist works in quick succession in the Criterion, all by British authors. These included works by the fledgling surrealist poets Hugh Sykes Davies, Charles Madge, Roger Roughton, the then up-and-coming Dylan Thomas, along with reviews on two books by David Gascoyne.

Fig 1. Cover of the London Surrealist Exhibition catalogue, 11 June – 4 July 1936. Photo credit: Prodan Romanian Cultural Foundation.

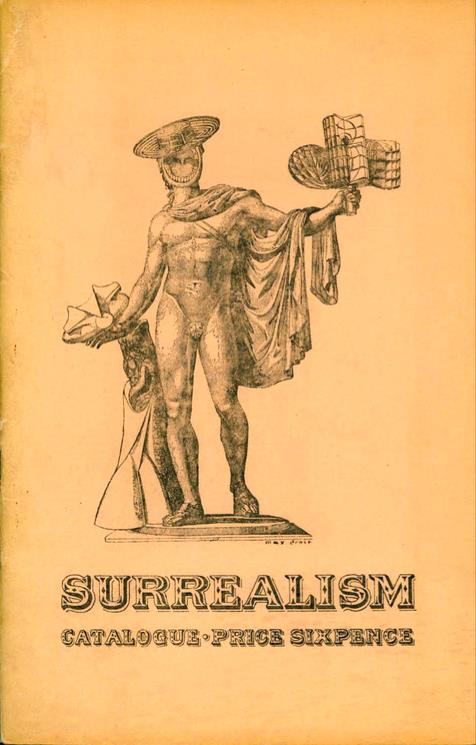

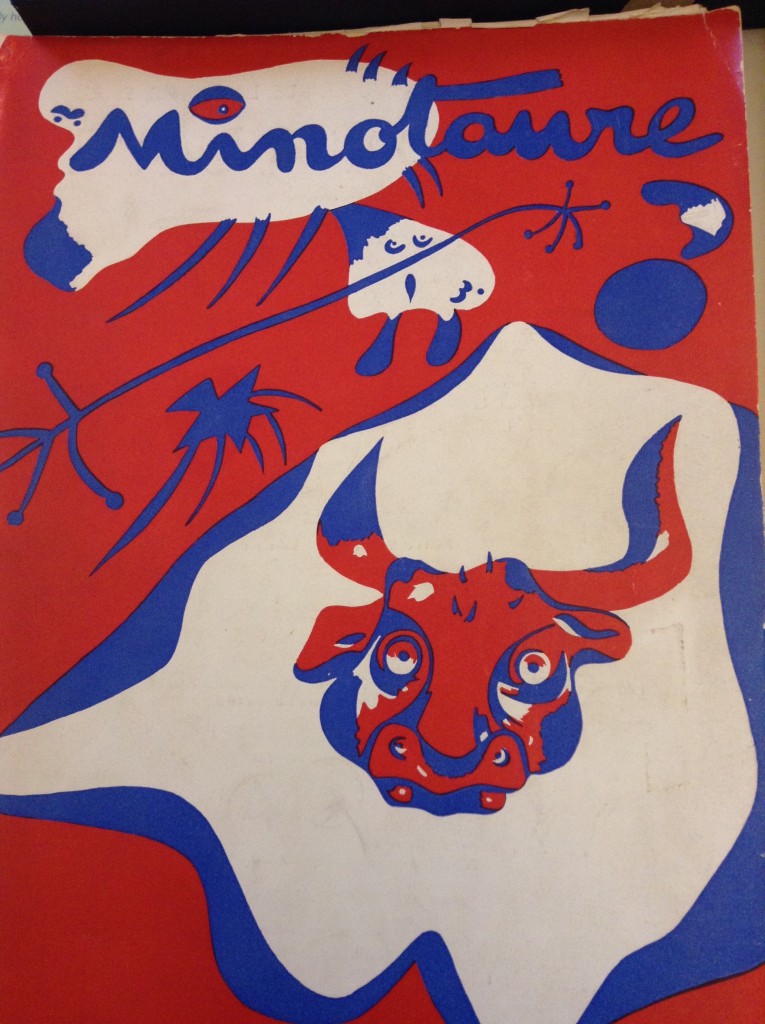

Fig 2. Cover of the Parisian high surrealist magazine, Minotaure, 7 June 1935, where Herbert Read published his provocatively titled ‘Why the English have no taste’, in which he argues for the necessity of a British surrealism. Photo credit: Xiaofan Xu, taken in the British Library.

As I progress with my doctoral thesis, I am increasingly fascinated by the reason behind such a sea-change on Eliot’s part. The sound of surrealism was certainly not music to the ears of Eliot’s respectable contemporaries. It was disreputable, to say the least. The 1936 London Surrealist Exhibition stirred a mild succès de scandale. Clement Greenberg, in his influential reflection upon the Avant Garde in 1939, also denigrates the surrealist plastic arts as being only secondary to the ‘good avant-garde’ in his classification, given its reactionary focus upon the ‘“outside” subject matter’ [2]. This brand of ‘bad taste’, however, might just have worked to Eliot’s benefit. Like Baudelaire who would ‘invent a cliche’ in defiance of the bourgeois propriety of his age, Eliot seeks to reshape literary taste for his own age by way of the ‘profane illuminations’ of surrealism [3]. Viewed in this light, Eliot’s publication of British surrealist works might thus be regarded as his combat with the banality of established taste (a difficult task given that he was himself part of the establishment) and an attempt to tap into the subversive potential of surrealist ‘bad taste’.

![Fig 3. Lobster Telephone, Salvador Dalí, 1936, © Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2016. Compare with the abject image in the chorus of Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral (1935): ‘I have tasted | The living lobster, the crab, the oyster, the whelk and the prawn.’ Photo credit: © Tate, London [2016] .](https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/wordsonwords/files/2016/04/Dalis-Lobster-Telephone.jpg)

Fig 3. Lobster Telephone, Salvador Dalí, 1936, © Salvador Dali, Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation/DACS, London 2016. Compare with the abject image in the chorus of Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral (1935): ‘I have tasted | The living lobster, the crab, the oyster, the whelk and the prawn.’ Photo credit: © Tate, London [2016].

[1] Eliot’s letter to Theodora Bosanquet, 21 June 1926, in The Letters of T. S. Eliot, ed. by Valerie Eliot and John Haffenden (London: Faber, 2012), III, p. 189.

[2] Clement Greenberg, ‘Avant-Garde and Kitsch’, Partisan Review, 6 (Fall 1939), pp. 34-49 (n. 2).

[3] See the analysis of Charles Baudelaire’s ‘Fusees’ in Svetlana Boym, Common Places (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 17.

[4] Graham Sutherland, ‘A Trend in English Draughtsmanship’, Signature, 3 (July 1936), pp. 7-13 (p. 11).

[5] T. S. Eliot, Notes Toward the Definition of Culture (London: Faber, 1948), p. 52.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

![Fig 4. Cover of Herbert Read’s The Green Child (Penguin, [1935] 1979). Photo credit: Xiaofan Xu.](https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/wordsonwords/files/2016/04/Herbert-Read-cover.jpg)

Leave a Reply