August 4, 2014, by James

St Kilda: Extreme Weather on the Edge of the World

St Kilda: an island community’s perception of weather

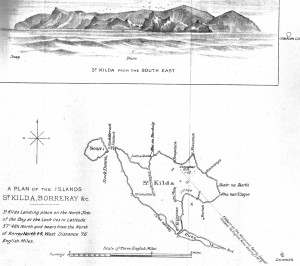

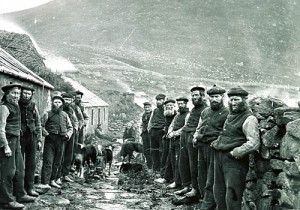

St Kilda is an isolated archipelago forty-one miles west-northwest of North Uist in the North Atlantic Ocean comprising the islands of Hirta, Soay, Boreray and Dun, as well as several sea stacks, and are the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It is an interesting case study of the impact of extreme weather given the traditional character of the island community, the hunter-gatherer economy and its peripheral and remote geographic location. The availability of an extensive body of contemporary literature describing island life, as well as photographs and surviving film footage (see link to the Scottish Screen Archives: http://ssa.nls.uk/film/0418) provides unique insight into the everyday life of the St Kildans until their evacuation in 1930.

In A Voyage to St. Kilda first published in 1698, Martin Martin (d.1718) described the fundamental importance of the weather on the lives of the inhabitants of the island of St Kilda, known as ‘the island on the edge of the world.’ [1] ‘They take the measure of going to the lesser islands from the appearance of the Heavens’, so wrote Martin, ‘for when it is clear or cloudy in such a quarter, it is a prognostick of wind or fair weather; and when the waves are high on the east point of the bay, it is an infalliable sign of a storm, especially if they appear very white, even though the weather be at that time calm.’ [2] He went on remarking about the weather patterns which the islanders observed and the way that they understood the weather of the islands:

‘If the waves in the bay [Village Bay] make a noise as they break before they beat the shore, it is also an infalliable forerunner of a west wind; if a black cloud appears above the south side of the bay, a south wind follows some hours afterwards. It is observed of the sea betwixt St Kilda, and the Isles Lewis, Harries, &c. that it rages more with a North wind, than when it Blows from any other quarter. And it is likewise observed to be less raging with the south wind than any other… They know the time of the day by the motion of the sun from one hill or rock to another; upon each of these the sun is observed to appear at different times; and when the sun doth not appear, they measure the day by the ebbing and the flowing of the sea, which they can tell exactly, though they should not see the shore for some days together: Their knowledge of the tides depends upon the changes of the moon, which they likewise observe, and are very nice in it.’ [3]

Given St Kilda’s remote and isolated location it was acutely vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather. In October 1860 St Kilda experienced a storm that removed the roofs of the houses which were flooded, destroyed the surrounding gardens and fields and with it the harvest. The islanders’ boats were lost and the breakwater damaged. Following this disaster, a campaign was launched for the relief of the islanders, who became increasingly reliant on external support for their existence. Weather was, therefore, influential in the survival of the St Kildans and can be seen as one factor, along with disease, demographic crisis, declining agricultural productivity, a lack of food and hastening hardship which led to the eventual abandonment of the islands. The last thirty six inhabitants of Hirta were finally evacuated in 1930 after a harsh winter and were resettled in Morven, Argyll.

Describing the climate and weather of St Kilda and its effects upon the community

In his ‘classic’ account: The Life and Death of St Kilda, Tom Steel wrote graphically about the impact of the weather, affecting the ability to supply the islands with goods and provisions from the mainland, the failure of crops and harvests, the inability to catch birds (fowling) which formed an important part of the hunter-gatherer economy and the problem of communicating with the mainland. This collectively added to the islands sense of isolation. The extracts given below describe the climate and weather of St Kilda, provides some instrumental meteorological data recorded by visitors to the islands and descriptions of weather extremes, specifically gales, storms and snow, as well as the significance of the prevailing wind direction:

‘The climate associated with St Kilda makes for an even greater isolation of any people that might be living upon the islands. In the spring and summer months the climate is often humid, and according to Mathieson – who, along with Dr Cockburn, visited the islands in 1927 to make a geographical survey – far from invigorating. While he and Dr Cockburn were on the island they kept a complete meteorological record from the months of April to October. During that time there were 627 hours of sunshine and eleven and half inches of rain. In Edinburgh, during the same period, there were 644 hours of sunshine and fourteen inches of rain. The average day-temperature was 63 degrees Fahrenheit, compared with 67 degrees Fahrenheit in Edinburgh. In the early spring month, St Kilda is frequently subjected to severe gales, especially from the months of February to April. The winter, however, is milder than might be expected; but there are often severe gales during the months October to November and there is also frequently much snow. According to Wilson who visited the islands in 1841, the weather was mild and when ice formed it was little thicker than a penny. The inhabitants, however, said that on many occasions the snow lay think upon the ground, and the nature of the land coupled with the winds made for fairly heavy drifts, capable at times of burying sheep.’ [4]

‘Storms, sudden and vicious, were common during the six month of the year from September to March. ‘It had rained almost incessantly from Saturday September 26th. Now three weeks, with the exception of three half days’, wrote Mrs MacLachlan in her diary on Friday, 16th October 1908. Stormy weather inevitably meant privation to the St Kildans. ‘Their slight supply of oats and barley,’ wrote Wilson in 1841, ‘would scarcely suffice for the substance of life; and such is the injurious effect of the spray in winter, even on their hardiest vegetation, that savoys and german greens, which with us are improved by the winter’s cold, almost invariably perish.’ Bad weather not only spelt ruin to the St Kildans’ crops, but could also lead to the islanders having to postpone or abandon a great deal of necessary work. ‘The people,’ continued Wilson, ‘are suffering very much from want of food… They literally cleared the shore not only of shell-fish, but even of a species of sea weed that grows abundantly on the rocks within the sea-mark… Now the weather is coarse, birds cannot be found, at least in such abundance as their needs require.’ Any part of the island’s provisioning process could be disrupted by unfavourable weather conditions, and a perilous situation could come about due to a lack of proper means of communication with the mainland. As the climate deteriorated with the passage of centuries–and evidence suggests that such was the case-the isolation of St Kilda became a more acute problem.’ [5]

‘The prevalent winds also contributed to the isolation of the people of Village Bay. Glen Bay on the northern uninhabited side of Hirta is open to northerly gales, while Village Bay, on the south-east side of the island is exposed to winds coming from the north-east to the south-east. Glen Bay was rarely used as a landing-place, save by a few stray trawlermen running before a storm, and the majority of landings throughout the island’s history were therefore confined to Village Bay which itself was beset with many problems. A landing could be made only if the wind was not blowing straight into the Bay: a storm could lick up the sea in waves tens of feet high, the spray of which often drenched the islanders’ homes, set a quarter of a mile from the shore.’[6]

Today, the National Trust for Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Ministry of Defence work in partnership to carry out conservation and research on the islands which are a designated World Heritage Site.

More information

M. Martin, A Voyage to St. Kilda: The Remotest of All the Hebrides. Or, Western Isles of Scotland (London, 1749).

T. Steel, The Life and Death of St Kilda (Edinburgh, National Trust for Scotland, 1965).

A. Fleming, St Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island (Macclesfield, Windgather Press, 2005)

In addition to the literary descriptions of island life, the school log books of St Kilda have been digitised and are available online see: http://www.cne-siar.gov.uk/archives/logbooks/stkildalog/index.html. There is also a wealth of printed literature. Information can also be found on the National Trust for Scotland’s St Kilda website see: http://www.kilda.org.uk/. For maps of Scotland see the National Library of Scotland website, http://maps.nls.uk/geo/find/.

References

- [1] Domhnall Uilleam Stiùbhart, ‘Martin, Martin (d. 1718)’, first published 2004; online edn, Jan 2008, 1073 words. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/18201.

- [2] M. Martin, A Voyage to St. Kilda: The Remotest of All the Hebrides. Or, Western Isles of Scotland (London, 1749), 62-63.

- [3] Martin, Voyage to St. Kilda, 62-63.

- [4] T. Steel, The Life and Death of St Kilda (Edinburgh, National Trust for Scotland, 1965), 18-19.

- [5] Steel, Life and Death, 19-20.

- [6] Steel, Life and Death, 20.

I’m a 77 yr old pensioner, as a young 24 yr soldier serving with RAOC in 1962 I was posted to Benbecular, and served on St Kilda. at the time there were 30 army personnel serving on the island consisting of 9 army corps, ie RAOC, REME, RASC, SIGNALS, ROYAL ARTILLERY,etc, it was usually a 3 week posting, but while I was there the weather was so rough they couldn’t take us off, consequently I spent 5 week” marooned ” on the island, they had to air drop urgently needed spares to keep the 2 radar stations running, I loved every minute of my stay there and would love to return just one more time, is that possible? could you please find out if it is, I have tried the Scottish Tourist Board but to no avail.

Thanks for contacting the project Albert. What a wonderful account of your experience of staying on St Kilda. I presume your deployment to the island was as part of ‘Operation Hardrock’ when there was a radar station established to act as an early warning radar station during the Cold War. I would appreciate it if you could write a more detailed account of the experience of 1962. The air dropping of supplies was widely used to supply remote areas during extreme winters.

You can visit St Kilda. Day trips run from Leverburgh on the Isle of Harris. For more information see: http://www.kildacruises.co.uk/. Please do not hesitate to contact me if you would like to discuss the project further (J.P.Bowen@liverpool.ac.uk). Thanks for reading the blog!

Hi james, trying to send E Mail about St. Kilda but it cant for some reason be accepted

Try the following:

j.p.bowen@liverpool.ac.uk

or alternatively the project email address: weatherextremes@nottingham.ac.uk

Similar to Albert Lloyds posting.

I was stationed there in 1958 with the RAF 5004 ACS . We had a week of force 9 gales, we were living under canvas so you can imagine the chaos.

Many thanks for your comment, Mike. Sounds ‘bracing’!! Always good to hear about personal experiences so if you have any other memories you can share, please do get in touch. Many thanks.

Thanks for your insight into life on St Kilda. I presume you were stationed on the island with the RAF Airfield Construction Branch building the radar station? Camping in a Force 9 sounds extreme! I would be extremely grateful if you could write down your memory of staying on St Kilda in more detail under the headings ‘My memory of extreme weather is…’, ‘Where did your story occur?’ (St Kilda) and ‘When did your story happen?’ You can either post them here, or feel free to contact me by email: J.P. Bowen@liverpool.ac.uk.

An important part of the project is how individuals and communities remember past weather extremes, so any information you can provide would be much appreciated. Thanks, James

James I will be in touch after Xmas. How can I send you some pics.

Mike

That would be great thanks Mike. You can send me picture by email, or alternatively my postal address is University of Liverpool, Department of Geography and Planning, Roxby Building, Liverpool, L69 7ZT. I look forward to hearing from you in the New Year. James