May 4, 2015, by James

The effects of weather extremes on the railways of Britain past, present and future.

The winter of 1963.

In November 2014 I visited The National Archives (TNA) at Kew in London to undertake a period of focused research concerning the impact of the extreme winter of 1963 on British agriculture. Whilst considerable attention has been paid to the winter of 1947-8, less work has considered the effects of subsequent extreme winters. The extreme winter of 1963, also known as the ‘Big Freeze’ of 1963, is one of the coldest winters on record in the United Kingdom. The Central England Temperature series which dates from 1659, records that you have to go back to the winter of 1683-4 (months of January -3oC, February -1oC and March 3oC) which was significantly colder, and the winter of 1739-40 – known as the ‘Great Frost’ (months of January -2.8oC, February -1.6oC and March 3.9oC) was only slightly colder than 1962-3.[1]

Booth’s snow survey of Great Britain for the 1962-3 season and the Meteorological Office’s ‘Monthly Weather Reports’ provide a detailed month-by-month account of the 1963 winter.[2] To briefly summarise, the beginning of December 1962 was very foggy, with a short wintry outbreak bringing snow on the 12-13 December. Towards the end of the month (22 December) a high-pressure system moved to the northeast of the British Isles having formed over Scandinavia and brought a cold easterly wind from Russia. A belt of rain over northern Scotland on the 24 December turned to snow as it moved southwards, reaching southern England on Boxing Day (26 December) and resulted in snowfall up to thirty centimetres in depth. Then followed a blizzard on the 29 and 30 December across Wales and South West England, causing snowdrifts up to six meters deep. There was widespread disruption with roads and railways blocked, telephone lines brought down and villages cut off for days. The snow remained for the next two months throughout England and Wales and periodically more snow continued to fall. Whilst there was sunshine, the lack of cloud cover meant that temperatures remained low. Throughout England and Wales, the long bitterly cold spell caused lakes, rivers and even the sea to freeze. The coldest winter for more than two hundred years in England and Wales finally abated in early March, but with the thaw came flooding, albeit nowhere near the scale of the 1947 floods.

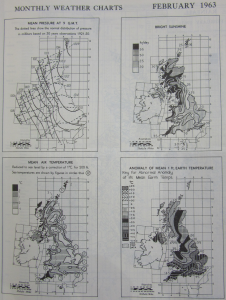

Map showing the monthly charts showing mean pressure, bright sunshine, mean air temperature and the anomaly of mean one feet earth temperature. Source: The Meteorological Office ‘Monthly Weather Report’ for February 1963, The National Meteorological Library and Archive, Exeter.

The impact of the winter of 1963 on British Railways (BR): ‘Lessons of the Winter.’

Whilst the reason for visiting TNA was to go through records of the Ministry of Agriculture, Farming, and Fisheries (MAFF), having an interest in railways, I could not help but request file AN 183/130 Lessons of winter 1963-1964 relating to the impact of the 1963 winter on railways in Britain.[3] It included statistics, plans and photographs and covers the period from 1 January 1963 through to 30 September 1966. A report commissioned by the British Railway Board entitled: ‘Lessons of the Winter’, dated 28 June 1963 provided a detailed analysis of the impact of the winter weather on the railway, an in-depth review of which is beyond the remit of this blog. Subjects covered included the effect on traffic levels, passenger train issues such as unpunctuality, cancellations, cold trains and the problems of train heating, a lack of information and disruption to suburban traffic. Also discussed was the implications for coal traffic, the behaviour of technical equipment namely points, signals, track, communications, water troughs and traction, and the effectiveness of snow clearance equipment. It offered some short- and long-term measures to take forward for the next winter and afterwards.

Archival film footage shot during the winter of 1963 provides a fascinating insight into the conditions experienced on the railway and attempts to clear snow drifts from the tracks by the use of snowploughs mounted on steam locomotives and also by simply digging by teams of track workers. Also shown are the freezing of signals, icy conditions on station platforms and the difficulties of moving milk and other goods.

Film footage from the Pathe newsreel: ‘Winter Railway Aka Clearing Railway Scenes, 1963.’ Source: http://www.britishpathe.com/video/winter-railway-aka-clearing-railway-scenes/query/winter+1963.

Snow (1963) by Geoffrey Jones.The British Film Institute National Archive. Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cl4pJwcE7JI.

Operation “Anti-Freeze”: Railways Prepare for Hard Winter.

Also included in the file is a press release titled: Operation “Anti-Freeze”: Railways Prepare for Hard Winter dated 2 October 1964, which records the efforts made by British Railways to ‘protect passenger trains and vital freight services against the hazards of another hard winter.’ This included making modification to steam heating and water pipes on mainline carriages and sleeping cars and the steam-generating plants of diesel locomotives. More point heaters were being installed to keep busy railway junctions free of snow and ice and larger and more effective snowploughs built to cut through deep snow drifts as well as smaller ploughs being positioned strategically across the network. This was part of ‘Operation Anti-freeze’ which a BR spokesman outlined:

‘We are trying to insure ourselves against the main difficulties of last winter when arctic conditions cause ice blockages in the heating of many main-line trains and froze signals and points.’

Operation Anti-freeze reflected a belief that the successions of mild winters had come to an end and that the BR Board were making plans on the assumption that future winters would be as severe as the last. Aside from the obvious problems with keeping traffic moving because of deep snow and frozen points, cold trains were one of the worst problems of the winter of 1963. Whilst electrically heated diesel and electrical multiple unit trains which were employed on suburban and short-distance services operated satisfactorily, there was trouble particularly on main-line locomotive hauled trains including sleeping cars, which were steam heated – steam being piped from the locomotive to passenger compartments, saloons and sleeping berths. Problems arose when the steam was turned off in very cold weather as the condensed water froze and ice built up, thus preventing the proper drainage of the system to the point that when the supply of steam was resumed, it could not easily pass freely to the heating equipment. BR tried to overcome this problem by improving drain valves as well as by changing the location and lagging of water pipes to toilet and sleeping compartments. It was hoped that this would reduce the risk of ice-blockage when the carriages were out of service, but also when running under winter conditions. These modifications were first to be made to sleeping cars and those trains kept as complete sets for use on important long-distance services.

‘We didn’t stop!’ Leaflet published by the Western Region of British Railways apologizing to passengers whose journeys were ‘not as comfortable as usual.’

Whereas with steam locomotives the steam heating was derived from the boiler of the locomotive, diesel locomotives had a separate steam-generating plant. BR undertook to modify these to improve their performance and reliability given that in the winter of 1963 many of them were over-taxed and broke down, making the issue of cold trains worse. The design was changed and new instructions issued as to the operation of the boilers. Minor modifications were also being made to diesel locomotives to improve their performance in frosty conditions.

The press release accepted that there ‘can never be normal services in abnormal conditions such as last winter’, with point heating being identified as a particular problem which caused delays to trains. It was specified that for the forthcoming 1964 winter there would be 2,180 point heaters in operation compared to 766 in the winter of 1963. It was also hoped that a further 300 would be installed during the course of the winter, the number nearly trebling. Figures specified give an impression of the regional distribution of point heaters, with over 700 being installed in the North East region at York, Darlington and Newcastle. The Southern, Western, Scotland, Eastern and London Midland regions had 485, 200, 129, 131 and 500 respectively. Given the high cost of installing point heaters – £105 per unit, they were only introduced at key junctions. It was estimated that the equipping of all the 100,000 or more switch-points across the network would cost approximately £10.2 million!

One of the most vivid images of the impact of the winter of 1963 on Britain’s railways is the use of snowploughs to clear tracks. The press release recorded that a new ‘heavy duty’ snowplough had been designed by the Scottish Region for use with diesel locomotives which had proved effective in clearing deep snow during the previous winter. Six more heavy ploughs were being built for the forthcoming winter and it was stated that other regions were considering a report produced by the Scottish Region to see if they might be of use to them. Miniature ploughs which had been fitted to diesel locomotives had been effective in clearing light snow, however, they had been generally inadequate in clearing the heavy drifts which had blocked lines in 1963. The press release made reference to calls for BR to adopt rotary ploughs and blowers such as used in Canada and Scandinavia, although it was pointed out that such ploughs were only effective in clearing fine powder snow which rarely fell in Britain.

Photography of a steam locomotive and snowplough pausing just south of Riccarton Junction in the Scottish Borders. Source: Waverley Route Heritage Association Archive.

Perhaps the most obvious effect of the extreme winter of 1963 was on the track which meant that there was a number of temporary speed restrictions imposed because of frost damage. It was outlined that frost damage, or ‘frost heave’ occurred when water beneath the track froze and expanded, causing the track foundation to shift slightly. The solution was good drainage and regional civil engineers had been addressing this issue.

The political context of the winter of 1963 and the impact of weather extremes on the railways of Britain in the twenty-first century.

The extreme winter should also be viewed in its wider political context. It contributed to the increasing unpopularity of Harold Macmillan and the Conservative government which was also satirised for restricting gas and electricity supplies when they were most needed, the former being replaced by Alex Douglas-Home and the latter eventually falling 15 October 1964.

But there is a more important general point to be made about the impact of extreme weather on the railways in Britain. The winter of 1963 is a classic example of how extreme weather can impact on Britain’s railway infrastructure. Whilst in hindsight the snows of 1963 can be viewed as an isolated event, today severe winters as well as other weather extremes including tidal surges and torrential rain inducing the erosion of track beds, embankments and structures, pose a serious threat to Britain’s Victorian railway infrastructure. The collapse of the iconic Dawlish Sea Wall (originally opening in 1846) which occurred in February 2014 is perhaps the most recent example. It was reopened 4 April 2014 and has been the focus of considerable debate since. Also closed in January 2014 was the Cambrian coast line from Dovey Junction after two sections of track between Tywyn and Barmouth were damaged by storm force winds and tidal surges which washed away parts of the sea wall protecting the track bed. The line to Barmouth was reopened by 10 February 2014 and later to Harlech on 1 May 2014 – the full line reopened on 1 September 2014 [4]. The total cost to the railway industry of the events of February 2014 has been assessed as being in the range of £40 million to £45 million.[5]

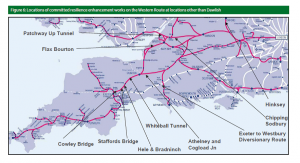

Weather related damage to Britain’s railways has highlighted the fact that the closure of many secondary routes in the 1960s and 1970s with the Beeching cuts has resulted in a lack of diversionary routes.[5] The Dawlish episode had major implications for a wide range of aspects of economic life in the South West of England and in heightening the region’s sense of remoteness. The ‘West of Exeter Route Resilience study’ was produced in the Summer 2014 by Network Rail with input from stakeholders which included local government, the business community, the Environment Agency and train operators following the Governments request for a report on options to maintain a resilient rail service to the South West peninsula. The report identified a series of new sustainable route options, including reopening the former London and South Western Railway (LSWR) mainline from Exeter to Plymouth, but only time will tell as to whether there is political will for this to be acted upon.

Whilst winters such as that of 1963 occur relatively infrequently, useful insights can be gained from the study of weather extremes in the past which can inform a society’s ability to be more resilient in the future. Climate change is one of the major problems which Network Rail faces in maintaining a largely Victorian railway network and whilst the high profile example of Dawlish sea wall remains at the forefront of people’s minds, there are other locations up and down the network which could be equally problematic and need to be addressed going forward in order to adapt to the twenty first century. For example at Cowley Bridge junction near Exeter river flooding poses a risk and the Chiltern line was recently closed between Leamington Spa and Banbury following a landslip as huge remedial works were undertaken, resulting in a lengthy line closure and great inconvenience for passengers.

References

- [1] G. Manley, Central England Temperatures: monthly means 1659 to 1973’, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 100 (1974), 389-405.

- [2] R.E. Booth, Snow Survey of Great Britain Season 1962-63. The Meteorological Office ‘Monthly Weather Reports’ have been consulted at The National Meteorological Library and Archive, Exeter.

- [3] The National Archives, Kew, London AN (Records created or inherited by the British Transport Commission, the BR Board and related bodies) 183/130 Lessons of winter 1963-1964.

- [4] BBC News, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-north-west-wales-26101654; http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-north-west-wales-27226047; http://www.networkrail.co.uk/news/2014/sep/Cambrian-Coast-railway-reopen/.

- [5] Network Rail – West of Exeter Route Resilience Study (Summer 2014), p. 3. Available online: https://www.networkrail.co.uk/publications/weather-and-climate-change-resilience/west-of-exeter-route-resilience-study.

- [5] Part 1: Report and Part 2: Maps of The Reshaping of British Railways written by the British Transport Commission, more commonly known as the ‘Beeching Report’ was published on the 27 March 1963 by Her Majesties Stationary Office, London.

More information

Network Rail Media Centre, http://www.networkrailmediacentre.co.uk.

First Great Western, https://www.firstgreatwestern.co.uk/contents/travel-advice/rebuilding-dawlish-railway.

The National Archives (TNA) Discovery catalogue, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/.

The National Railway Museum, York (Research and archive), http://www.nrm.org.uk/ResearchAndArchive.aspx.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply