June 9, 2014, by James

Getting into the Archive – The Hingham Town Book (part 2)

The Hingham Town Book

A few weeks ago, Lucy reported on her recent visit to Norfolk Record Office. A source which I alerted her to following discussion with members of the British Agricultural History Society at the annual spring conference was the Hingham Town Book. As Lucy noted in her blog, the Hingham Town Book, which mainly contains the parish accounts of the Churchwardens, Constables and Overseers, includes a small number of informative entries relating to weather, extracts of which were included in the blog dated 24 April 2014.

As a county, Norfolk has had a highly commercialised agrarian economy since the medieval period which intensified throughout the early modern and modern periods. Today, agriculture still forms an important part of the economy. Hingham, a rural market town approximately 17 miles from Norwich, is typical of Norfolk parishes as it historically had a rural farming economy characterised by a combination of cereal growing and livestock husbandry.

This blog provides some brief context as to the significance of this source, not simply in the way that it describes the weather in a given year, but in relation to the system of farming in Norfolk and the wider structural changes in English agriculture during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Weather as a determining factor

In a paper published in Agricultural History (‘Weather and agricultural change in England, 1660-1739’, Agricultural History, 63, 2 (1989), 77-88), Mark Overton cited the example of Hingham Town Book and, in particular, the entry for 1681:

‘1681 – This year began a drought about the middle of March & continued till the beginning of July by reason of which we had little or no hay for that it was found for great prices before the rains. But in July it pleased god to send […] as we had in this town a good cropp of all grains & beyond hope or […] for when we feared a famine we had a greate plenty; & a want of hay was supplied by farming of turnips.’

It is clearly indicative of the occurrence of a period of drought which resulted in a lack of hay and what had been grown between mid-March and early July was sold before a period of heavy rain in July hampered the hay harvest. Overton argued that this led to an insufficiency of hay for animal fodder which the Hingham Town Book implied was compensated for by the growing of turnips, an important root crop which he suggested was introduced in Norfolk, partly in response to the weather which deteriorated in the second-half of the seventeenth century. The diffusion of turnip husbandry intensified in the period after 1750, although as turnips were susceptible to disease and hard winters they were later replaced by new root crops namely the swede and mangel.

But what was the wider significance of the weather described in the Town Book? To what extent did the weather influence agricultural change? How did farmers respond to such weather events as those described in the Hingham Town Book? And, were changes in weather and climate an important factor in providing the impetus for developments in farming practices?

It is plausible that the adoption of turnips which could be planted as late as August was a direct response to short and/or long-term weather events such as the incidences of drought (recorded for Hingham for the years 1681, 1684 and 1685) and heavy rainfall, as well as more long-term changes in weather patterns and climate change. However, a purely economic view fails to take into consideration other factors. For instance, what about decision-making and the ability of farmers to shape the course of the rural economy of Norfolk? How many times did the hay harvest have to fail before farmers decided to abandon hay in favour of turnips? Can land which is used for hay be suitable for turnip production? Also, can the incidences of extreme weather noted in the Hingham Town Book be linked to periods of drought or heavy rainfall in the Norfolk Broads and the East Anglian case study region more generally? These are all questions that require further consideration.

Agricultural Revolution and Norfolk agriculture

The introduction of turnips from the 1630s and other root crops in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been viewed as a significant factor in the much debated agricultural revolution, although they did not themselves have a major impact on productivity or output. Historians who have examined the notion of an agricultural revolution on the basis of a population-resources model, have suggested that population growth provided the stimulus for advances in farming practices, such as, the introduction of turnips. Nevertheless, such a view has been challenged by economic historians who argue that farmers adopted technological innovations when they saw a rise in prices and an upturn in the market more generally. Turnips provided a much more intensive form of animal fodder, allowing for a reduction in permanent pasture which, allowed for an increase in the extent of the arable land and a subsequent rise in crop yields – increasing land productivity. However, Overton suggested that the initial introduction of turnips (and clover) had more to do with averting risk and mitigating the effects of bad weather rather than raising land productivity as part of a Norfolk four-course system. He also pointed to it corresponding with the peak of the ‘Little Ice Age’ in the late seventeenth century and the occurrence of frequent periods of droughts. Clearly, changes in weather and climate could have important ramifications, not simply in relation to the decision to increase the growth of turnips and the introduction of root crops, but more importantly, affecting crop yields and prices, and in some instances resulting in food shortages in a period when the population of England was growing dramatically.

Caution should however be applied to this interpretation as it is important to recognise the wider agricultural context and to view the adoption of turnips as a response to the more intensive production of cattle and the need to stall cattle for longer to fatten them more quickly, rather than allowing them to graze. Farmers simply could not substitute hay for turnips. Indeed soil type is also an important consideration, as whilst hay was suited to light clay and sandy soils, turnips prefer moist, light, rich, sandy, loamy soil which can form a good seedbed. In this sense, it could be conversely suggested that the growth of turnips should be viewed as an addition to hay production and that the reference to the shift to turnips in the example of the Hingham Town Book, was less about the weather, but rather crucially reflected the increasing adoption of turnips as the farming system intensified in favour of livestock husbandry. Hopefully, further research on the East Anglia case study region might be able to shed further light on this issue.

Charles Townshend, the 2nd. Viscount Townshend of Raynham in 1687, popularly known as: ‘Turnip Townshend.’ After he retired from politics in 1730, he turned his attention to his estate in Norfolk, introducing a new type of four crop rotation which included turnips along with wheat, barley and clover. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London.

For more information

- M. Overton, ‘Weather and agricultural change in England, 1660-1739’, Agricultural History, 63, 2 (1989), 77-88.

- M. Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy, 1500-1850 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996).

- S. Wade-Martins and T. Williamson, Roots of Change: Farming and the Landscape in East Anglia, c.1700-1870 (Exeter, University of Exeter Press, 1999).

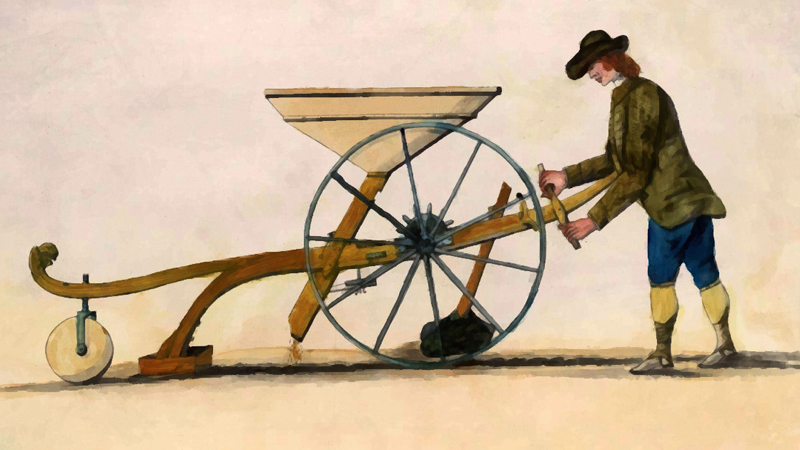

James – thank you for these thoughts on the Hingham Town Book material and its wider content, a really interesting and early source of information on extreme weather events. I came across some more turnip references whilst working at The Hive in Worcester last week and I feel sure there will be plenty more! The feature image in your blog is lovely – where is it from?

Glad you found the blog interesting Lucy. It is important to view such local examples as the Hingham Town Book in their wider economic, social and landscape context, and also to think critically about how historians and historical geographers interpret such material. If you search for seed drill in Google Images the image should appear.