March 10, 2014, by James

Getting into the archive – Shrewsbury in ‘The Great Frost’ of 1739

‘The Great Frost’ of 1739

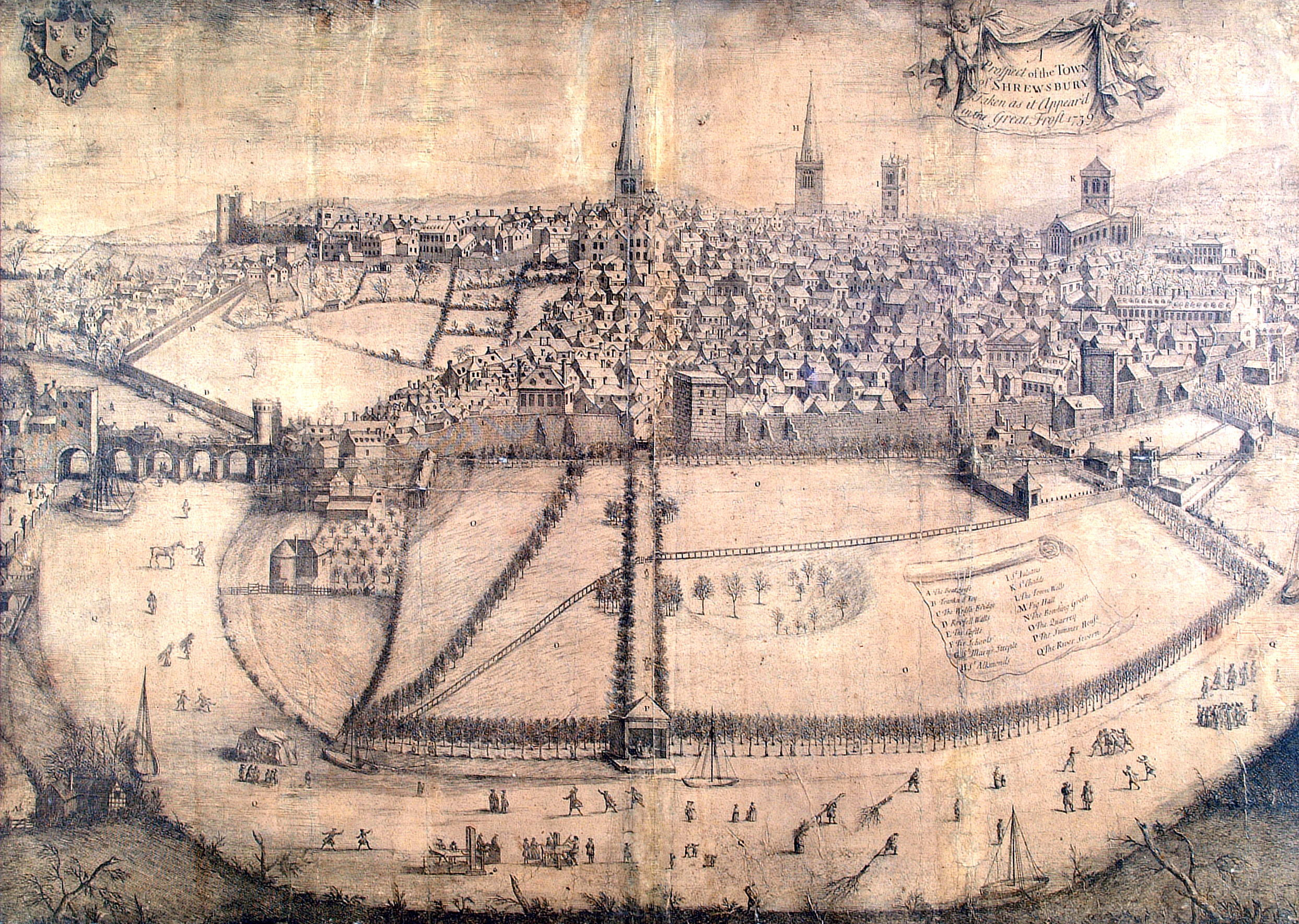

Whilst the frost fairs held on the River Thames, London in the years 1608, 1683-4, 1789 and 1814 are well recorded in both documentary evidence and artistic representations, little is known about comparable events in provincial town and urban settings throughout England. The engraving by an unknown artist shows a panoramic view of Shrewsbury, Shropshire in the winter of 1739 during ‘The Great Frost’ when a fair was held on the River Severn, also known as ‘Sabrina’ when it was frozen.

Various activities are shown taking place including ice skating, a horse and rider and groups of people congregating and playing games. Others appear to be carrying wood, presumably for fuel given the harsh winter conditions. Several boats, namely Severn trows are also shown frozen hard in the ice. Included in the scene is a printing press, demonstrating the thickness of the ice. It illustrates many fascinating details of the town as it was in that year. The view is from the west and shows the medieval town wall still virtually intact at that time and identifiable are numerous landmarks including the castle, the old medieval Welsh Bridge, the Quarry – a landscaped riverside park, the chimneys and roofs of the townscape and the spires of St Alkmund’s, St Mary’s and St Julian’s churches and Shrewsbury Abbey.

Daredevil: Robert Cadman (1711/2–1740).[1]

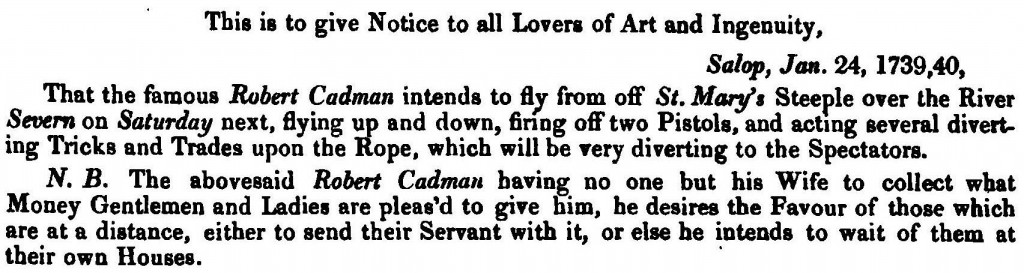

A popular form of entertainment at fairs and markets were flying men, the 1730s witnessing something of a craze for rope dancing, sliding and walking. In 1739 Robert Cadman or Kidman and his wife appeared at Shrewsbury to restore the damaged weathercock of St Mary’s Church. As part of the town’s celebrations of ‘The Great Frost’, Cadman, a well-known steeplejack and rope-slider and a native of Shropshire having been born at or near Shrewsbury, attached a rope from the spire of the church across to the Gay Meadow on the other side of the river. As on previous occasions, he entertained the crowd with a variety of rope stunts. A handbill dated 24 January 1740 heralded his flight on 2 February from St Mary’s steeple over the Severn to the meadow opposite.[2]

However, the rope broke causing him to plummet suddenly to his death. Following the event it was later said that ‘just before he set out on his mad career, he found the rope a little too tight, and gave the signal to slacken it: but that the persons employed, misconceiving his meaning, drew it tighter. It snapped in two as he was passing over St Mary’s Friars, and he fell amid the thousands of spectators.’[3] It was recalled that his body, ‘after reaching the earth, rebounded upwards several feet’, the ‘severed rope smoking in its serpentine descent.’ It was observed that his wife, who had been passing round the hat, ‘threw away her money in an agony of grief’ and ran to him.[4] A mock-heroic, yet sympathetic poem was written by an unnamed ‘J.A.’, presumably an eyewitness and published in the Gentleman’s Magazine:

‘Nothing could ought avail but limbs of brass,

When ground was iron, and the Severn glass.’[5]

Commemorating Cadman

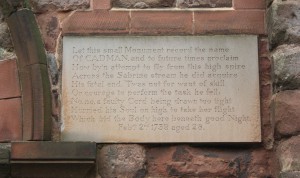

Photograph of the commemorative plaque in memory of Robert Cadman located by the main door of St Mary’s Church, Shrewsbury.

Cadman’s death was likened to Greek and Roman mythology in verses that record vivid details of his final flight. The London Evening Post (7 Feb 1740) reported that Cadman was killed ‘by the cutting off of the Rope where it came through the Steeple, it being fasten’d to the Frames of the Bells.’[6] This dramatic death reinforced his reputation and ended the golden age of flying. Subsequently Cadman was buried at St Mary’s Church, Shrewsbury on 4 February 1740 and is commemorated by a ten line epitaph.

An impression of Cadman’s performance can be gained from William Hogarth’s painting of Southwark Fair, 1733 in which he is featured flying from a church tower to the ground. The celebrated historian of Birmingham William Hutton (1723-1815), born in Derby wrote in his history of his home town:

‘No amusement was seen by the rope; walls, posts, trees, and houses, were mounted for the pleasure of flying down: if a straggling scaffold pole could be found, it was reared for the convenience of flying.’[7] He referred to Cadman, a ‘small figure of a man… composed of spirit and gristle’, who had earlier entertained the crowds at Derby in October 1732 by sliding from the steeple of All Saints church to the bottom of St Michael’s church, a horizontal distance of eight yards. Hutton described his spectacle in detail writing: ‘A breast plate of wood, with a groove to fit the rope, and his own equilibrium, were to be his security, while sliding down upon his body, with his arms and leg extended. He could not be more than six or seven seconds in this airy journey, in which he fired a pistol and blew a trumpet. The velocity with which he flew, raised a fire by friction, and a bold stream of smoke followed him.’[8] He performed the act for three successive days, descending twice. He even once marched up the rope, taking him an hour during which he ‘exhibited many surprising achievements’, which included sitting with his arms folded, lying across the rope on his back and then his belly, blowing the trumpet, swinging round, hanging by his chin, hand, heels, and toes.[9] Hutton knew about Cadman’s fate as he wrote: ‘Though he succeeded at Derby, yet, in exhibiting soon after at Shrewsbury, he fell, and lost his life.’[10] Unsurprisingly accidents were not uncommon and are recorded elsewhere in England.[11]

References

- [1] Page Life, ‘Cadman, Robert (1711/12–1740)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, October 2005; online edition, May 2007 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/64323, accessed 6 Feb 2014].

- [2] Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury P257/U/3/1.

- [3] H. Owen and J.B. Blakeway, A History of Shrewsbury (1825), 410.

- [4] Owen and Blakeway, History of Shrewsbury , 410.

- [5] J.A., ‘On the death of the famous flyer on the rope at Shrewsbury’, Gentlemans Magazine, First Series, 10 (February, 1740), 89.

- [6] London Evening Post (7 Feb 1740).

- [7] W. Hutton, History of Derby (London, 1817), 205.

- [8] Hutton, History of Derby, 204.

- [9] Hutton, History of Derby, 204-5.

- [10] Hutton, History of Derby, 205.

- [11] For example, there is a similar account of Thomas Pelling, the flying man of Pocklington in the East Riding of Yorkshire who fell to his death. When he began his descent the rope became too slack, he called out for the windlass to be tightened but his instruction was misunderstood and the rope was loosened further and he plummeted onto the battlements at the east end of the chancel and fractured his skull. He died two days later, and was buried at the spot where he fell. See the blog for the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York: http://borthwickinstitute.blogspot.co.uk/2013_05_01_archive.html, accessed 6 Feb 2014].

What a wonderful read! I wonder what people would make of Cadman today!

I came across Robert Cadman’s plaque at St Mary’s many years ago, it made an impression on me. Thanks for the telling the story in its context.

It’s not the Abbey on the right btw, it’s Old St Chad’s (demolished not long after).

“Early in the summer of 1788 cracks started to appear in the north-west crossing pier, one of the four pillars supporting the central tower. The churchwardens subsequently asked Thomas Telford, then a year into his position as the County Surveyor of Public Works, to inspect the church’s fabric. Telford reported that graves dug too close to the tower’s shallow foundations had weakened the structure and that the whole north side of the nave was in a dangerous state, augmented by the near total decay of the principal roof timbers. He subsequently recommended that the tower with its heavy ring of bells should be taken down immediately so that the shattered pier might be rebuilt with the decayed roof timbers being renewed and the north-west wall of the nave being secured. A vestry meeting considered Telford’s proposals to be a gross exaggeration and a stone mason was ultimately employed to cut away the cracked sections and underpin the pillar, without removing, or even lessening, the vast weight of the tower and bells. On the evening of 8 July, two days after work had commenced, an attempt to ring the bells for a funeral caused the tower to shake so violently that the Sexton immediately evacuated the building. The following morning, as the clock struck four, half of the tower collapsed, taking the roof and large sections of the church with it.”

Thanks for the correction and additional information – complete with another extreme weather reference!