October 5, 2015, by Jon Henderson

Rome’s Titanic

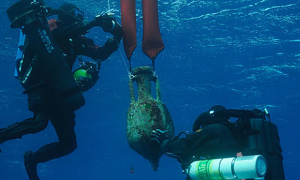

The first year of controlled excavation at the Antikythera wreck has just been completed and the joint Greek-American team have announced their findings.

I recently wrote in The Times about the return of archaeologists to Antikythera – the site which produced one of the richest cargos ever recovered from an ancient wreck when it was first salvaged in 1901.

Finds from 1901 included a spectacular series of classical bronze and marble statues, coins, storage jars, pottery and other works of art, as well as the wrecks most celebrated find, the Antikythera Mechanism .

Though no more parts of the famed mechanism were recovered, the 2015 excavation did reveal a cache of artefacts including a bronze armrest which could have been part of a throne, an intact amphora, a small table jug (known as a lagynos) and a rectangular chiseled stone, probably a statuette base, as well as broken ceramics, a piece of a bone flute, and broken bits of glass, iron and bronze.

Not perhaps the riches that were first hoped for but this is just the beginning. The site still remains largely unexcavated (the Greek sponge divers salvaged the large pieces of statuary from the seabed but will have left much of the archaeological deposits intact) and there will doubtless be more to follow in the coming seasons.

Artist impression of a Roman cargo ship

The wreck was that of a Roman galley, carrying a rich cargo of looted Greek treasures bound for Roman markets in Italy, which sank off the coast of the Greek island of Antikythera around 60 to 70 BC.

For me one of the most significant aspects of the new work is that it has revealed that the Antikythera ship as THE biggest sea going ship yet discovered from the ancient world.

Historians have long assumed based on the existing written accounts that the ship was a large merchant ship some 30m long and 10m wide. However, the new survey work carried out by Brendan Foley and his team has revealed it was in fact at least a staggering 50m long and more than 20m wide. Wooden planks recovered from the vessel are 11cm thick – this is the thickest known ship timber from the ancient world, the closest parallel being the Roman Lake Nemi ships which were 9cm thick (the Nemi ships were built as elaborate floating royal palaces in the 1st century AD). What is more, the Antikythera planks were covered in lead sheeting and the nailing pattern suggests that the lead sheeting came first with the planking added later. This is a major innovation demonstrating not only significant advances in ship technology but a major investment in capital and resources to build such a vessel.

This massive ship was in the process of shipping a major art collection from Greece when it sunk (the richest yet discovered). The wreck dates to the period when the Roman elite were rich enough to be able to commission ships to bring Roman statues and sculptures to Italy so they could display them in their gardens and coastal retreats to illustrate their own status. It reveals the influence of Greek art and culture on the developing Roman world and how the Romans systematically plundered the monuments and sanctuaries of Greece.

In the construction of this ship we are seeing the beginnings of what was to become the Roman Empire. To produce such a vessel required an advanced industrial base – requiring slaves and specialists to work with the noxious lead. Ultimately they produced massive, technically advanced vessels taking to the seas with one purpose – to siphon off the wealth of Greece to what will become the Roman Empire. This is after all what empires have always done and these stolen riches became part of the wealth of Rome that allowed it to further expand.

Was the Antikythera ship so large and its haul so great that it had to be state sponsored? Or was it commissioned by a very rich individual? If so who was it? The wreck has been linked to written records of senators such as Sulla in 86 BC commissioning vessels to transport treasures from the Greek world to Italy. Coins from Antikythera, recovered by Jacques Cousteau in 1976, suggest the wreck dates to around 60 BC. This dates to the period when Pompey was wiping out piracy in the Mediterranean to ensure the safe passage of trade. Antikythera was known as a pirates nest and the suppression of piracy was crucial to Rome laying the building blocks for the Pax Romana and Empire.

Whatever the case the sheer scale of the Antikythera ship reveals the growing strength of Rome – it was a floating symbol of imperial Rome’s growing maritime power and dominance at sea. The shipping of grain to Rome was essential to its survival – without this lifeline and supply established through control of the seas there would have been no Roman Empire.

The decision to build ships on the scale revealed at Antikythera was a significant turning point for Rome. Even in modern history, few nations are able to produce vessels of this scale. Examples include Britain’s Royal Navy in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries AD, which established control over a vast trans-global maritime empire and whose ships controlled shipping lanes and suppressed piracy. The modern US Navy is the current equivalent, projecting power worldwide through the deployment of large naval fleets, submarines and aircraft carriers. And of course China is now developing its own fleet of aircraft carriers, delivering a clear sign that China is not only an economic powerhouse, but a maritime power, too.

Think