June 14, 2017, by David Felipe Alvarez-Amezquita

No Break for Nestlé from the Court of Appeal: Refusal of KITKAT shape mark upheld

Post by Lynne Chave

Lynne is a PhD candidate at the School of Law. Her research investigates the extent to which trade mark and design protection of product shapes overlap.

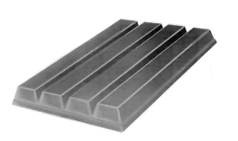

The decision last month from the Court of Appeal of England and Wales is the latest stage in Nestlé’s attempt to gain trademark registration for the shape of the four-fingered KitKat bar. The question before the appeal judges was a simple one: has the KitKat product shape, when stripped of all other identifying mark (as shown below), acquired a ‘distinctive character’ resulting from Nestlé’s long-standing use?

According to Article 4(1)(a) of the EU Trade Mark Directive 2015/2436, ‘distinctiveness’ is an essential requirement if a sign is to qualify as a registrable trade mark. A trade mark’s key function is to help consumers to make informed choices between competing products. Distinctiveness signifies a sign’s capacity to distinguish the commercial origin of the goods bearing the mark from the same or similar products which originate from other sources.

Given that KitKat bars have been made in the same shape for over 80 years, and that Nestlé report that more than one billion KitKat bars are eaten every year in the UK alone, Lord Justice Vos was quick to concede that most would find it ‘surprising that these simple words have caused so much litigation and so many erudite authorities.’ And yet, trade mark registries and courts, both within the EU and further afield, have failed to reach consensus in respect of this particular shape.

Initially, the UK Intellectual Property Office (‘UKIPO’) was satisfied, based upon the evidence of use which Nestlé submitted, that the product shape had acquired a distinctive character. It changed its position, however, based upon the opposition to the application filed by Cadbury. Nestlé’s appeal to the High Court against refusal of the trade mark application was also unsuccessful. This decision is the decision under appeal. Considering similar evidence of use, the Singapore Court of Appeal has also held recently that the shape is non-distinctive in Singapore.

Conversely, Nestlé has managed to secure trademark registration for the same shape in other countries including Australia, South Africa and Canada. As in the EU, these jurisdictions only protect distinctive product shapes as trade marks. Of most interest is the decision of the General Court of the EU concerning Nestlé’s corresponding European Union trade mark (EUTM). Considering the same evidence of use adduced in the UK proceedings, the General Court was satisfied that the shape mark was distinctive in various member states, including the UK, where evidence of use had been adduced.

Taking stock, what is the crux of this dispute, and did the view of the High Court or that of the General Court prevail? The issue hinges upon the fact that ‘distinctiveness’ is a term of art in trade mark law. Thus, its legal meaning is subtly, but significantly, different to its ordinary meaning. The mere fact that a sign is unusual or unique does not mean that it is ‘distinctive’ under trade mark law. In fact, it is generally accepted that unless a business takes steps to educate consumers, potential purchasers are unlikely to make assumptions about the origin of a product based solely upon its shape.

In these proceedings, it was not in dispute that most consumers would recognise the product and associate confectionery products of this shape with Nestlé. Indeed, Nestlé’s main evidence took the form of a consumer survey in which over half of the respondents, when shown the unadorned shape, made a connection between the representation and ‘KitKat.’

However, following an earlier reference in the proceedings, the CJEU has already clarified that acquired distinctiveness requires more than just recognition and association – which is all that the UKIPO and the High Court considered that Nestlé’s evidence showed. Rather, an applicant seeking registration must demonstrate that consumers will perceive the goods as originating from their company, rather than from any other source, because of the shape.

Ultimately, the Court of Appeal agreed with the High Court and UKIPO. In establishing the perception of the average consumer, the Appeal Court carefully considered how the product shape had been used. While large quantities of the shaped goods had been sold, the Court noted that the product was always promoted using the highly distinctive KitKat brand. While this was not conclusive, it made it far more probable that the public would perceive the shape as indicating the nature and characteristics of the goods, rather than being a ‘badge of origin’.

In addition, the Court of Appeal reiterated that earlier CJEU references (C-299/99 [64] and C-353/03, [26]-[29]) had already established that a product shape would only acquire a distinctive character as a result of ‘trade mark’ use. While the Court acknowledged that this did not require explicit promotion of the shape as a trade mark, use of this kind would undoubtedly assist. In this case, the Court was unpersuaded that there had been any trade mark use. Most of Nestlé’s marketing featured the wrapped form of the product, meaning that consumers would only get to see the shape of the goods after sale.

The Court of Appeal also considered the important distinction between consumer ‘reliance’ and ‘perception’ – a point which Lord Justice Kitchin acknowledged might be ‘elusive’ to non-trade mark lawyers. The Court confirmed that to satisfy the CJEU test, it was not mandatory for an applicant to demonstrate that consumers relied upon the shape when making their purchasing decisions. However, if an applicant could prove that its consumers did rely upon the shape as an indication of origin, then this would be sufficient to establish acquired distinctiveness. ‘In this context, reliance is a behavioural consequence of perception’ [82].

In rejecting the appeal, the Court of Appeal declined to follow the General Court’s finding that Nestlé’s survey evidence did enough to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness of the shape in the UK. The Court noted that it was not bound to follow the General Court’s evaluation of the evidence of use. In any event, the UK Court was not satisfied that the General Court had applied the CJEU guidance correctly. It highlighted passages which suggested that distinctiveness had been found based upon recognition and association only [100].

The conflicting conclusions of these two senior courts is indicative that this latest decision does not mark the end of the matter. The potentially flawed decision of the General Court has been appealed to the CJEU already (pending as Case C-84/17P), thereby delaying the fate of the contested EUTM. In addition, while the Court of Appeal considers that the test for acquired distinctiveness has been settled by the CJEU, it is possible that Nestlé will seek leave to appeal this case to the UK Supreme Court. In the meantime, the KitKat shape is simultaneously distinctive (EUTM) and non-distinctive (UKTM) in the UK – a far from satisfactory position.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply