April 12, 2017, by Rights Lab

Advancing supply chain management for the challenges of Modern Slavery

By Dr Alexander Trautrims

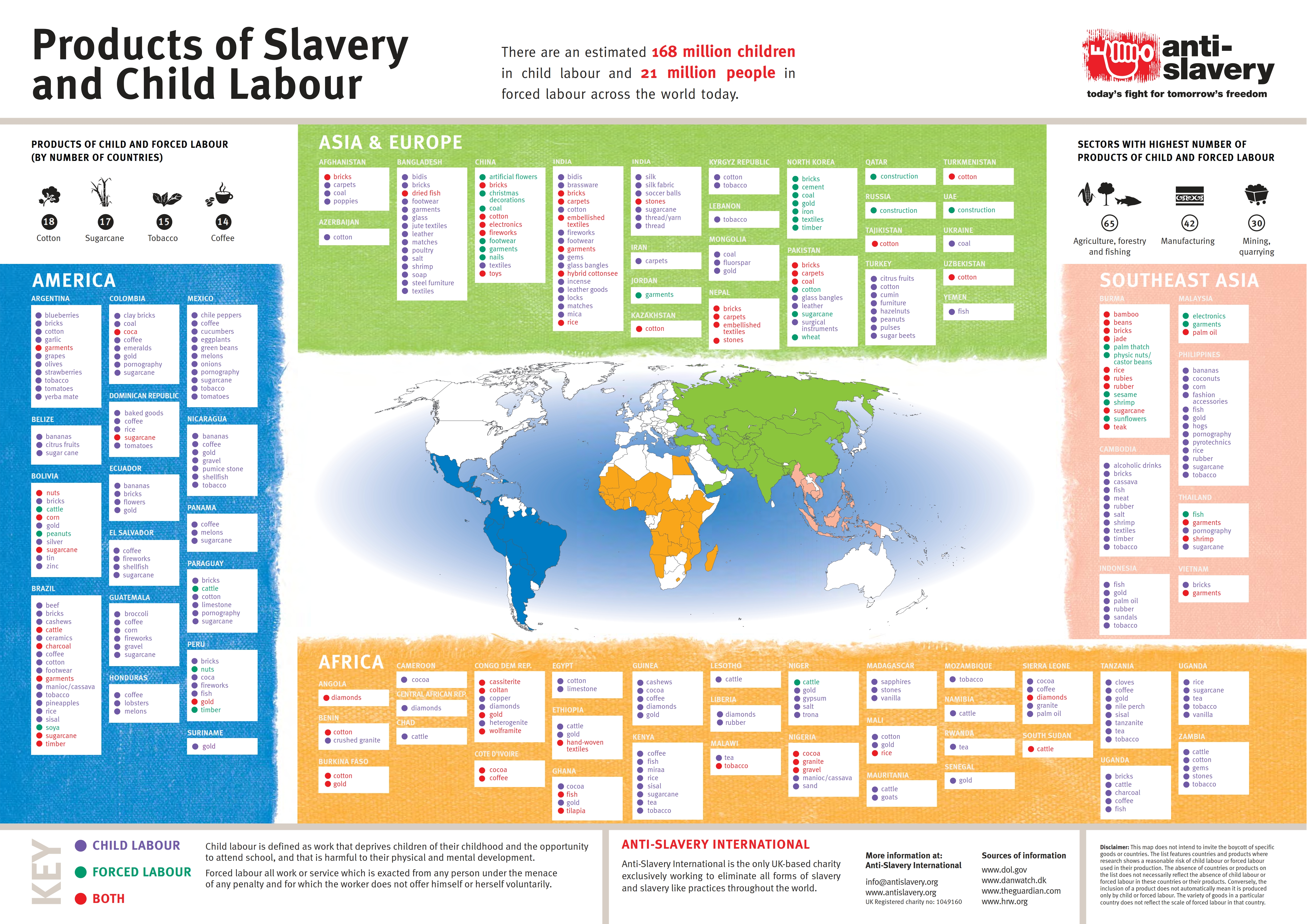

Supply chains that compete solely on price with little opportunity to differentiate from the competition or to compete on value-added propositions, are almost naturally drawn towards modern slavery and other unethical labour practices. This is particularly the case for industries where low skill labour is a key resource and in places where automation cannot economically compete with the abundant supply of such labour resources. The concept that labour in production and service supply chains became a disposable commodity is something one of the University of Nottingham’s researchers, Professor Louise Crewe, calls Biocommodification. Contemporary ‘western world’ supply chains are predominantly exposed to this risk in countries from which they source, but criminal, unethical labour practices can be part of supply chains in the ‘developed world’ too.

Eradicating modern slavery and unethical practices from supply chains is however more complicated than most people realise. Many contemporary supply chains are operating globally across multiple jurisdictions, and can be highly fragmented and complex. Although globalisation is not a new phenomenon, ordinary supply chains are today longer and rely more on overseas sourcing than ever before. As supply chains keep stretching further, maintaining visibility and control of the supply chain becomes more challenging and is often lost.

Global supply chains rely on mechanisms such as trading, wholesale and agents who are middlemen that enable the access to foreign markets and supply. But they also anonymise the supply chain as they are consolidating and distributing supply and demand from various sources and to various customers. A commodity trader will buy and sell products, often without ever seeing or touching the product and without knowing producer or customer in person. The trader acts as an anonymization point, making it—depending on the product—much harder or impossible to establish the link between the initial producer and the final customer.

Whereas technology enables us to run these global supply chains with their anonymisation points, technology is also a crucial enabler in de-anonymising supply chains. Already, technology allows us to cut out middlemen and to engage directly and more closely with suppliers further afield. But beyond communication with suppliers, technology can also be a way to keep track of products along the supply chain and to scrutinise businesses and their operations by using externally available data sources and proxies.

The challenge of eradicating modern slavery and other unethical labour practices from supply chains is also a great opportunity for advancing an organisation’s supply chain and for advancing the supply chain profession. Understanding the supply chain from producer to end customer is not only useful for controlling the supply chain against unethical practices but also good practice and necessary input for optimisation and resilience of the supply chain.

Medical doctors and accountants are amongst the professions accustomed to being held responsible for malpractice in their work, particularly when it causes harm to others: why should supply chain management professionals face lower expectations?

Dr Alexander Trautrims is a Lecturer in Supply Chain and Operations Management at Nottingham University Business School. He leads The Unchained Supply, a University of Nottingham research project that draws upon a pioneering programme of antislavery research to develop and test new solutions to the problem of slavery in supply chains.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply