January 6, 2025, by Rupert Knight

Map-making, path-finding, and bridge-building: closing the gap between working-class pupils and their peers.

In this post, Brittany Wright from L.E.A.D. Academy Trust reflects on ways to improve educational outcomes for pupils from working-class backgrounds.

As teachers and leaders, we know how important our work is to the lives and life chances of our pupils. As well as providing a high-quality education for pupils during their school days, government policy has framed our work as key to making society fairer. In 2007, Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown saw schools as “the greatest force for social progress” . Conservative Schools Minister Nick Gibb’s 2016 speech described schools as “engines of social mobility” . Across the political spectrum, ‘closing the gap’ between pupils from working-class backgrounds and their more privileged peers has been an aspiration for decades and is a key aim of the new Labour government.

In this blog post, I’ll explore what my doctoral research tells us about how teachers can provide a fairer education for pupils from working-class backgrounds.

Social class in school

In England, socio-economically disadvantaged – or under-resourced (Major and Briant, 2023) children are eligible for the pupil premium, a sum of money allocated to individual schools on a per pupil basis to offset the inequalities they face, as documented by the DfE. There is a significant gap in the levels of attainment between working-class young people and their more privileged peers. This gap widens from the earliest years of schooling through to Year 11 (Choudry, 2021).These inequalities manifest in various ways in our classrooms and schools. For example, during secondary school, working-class learners are more likely to be placed in bottom-sets (Archer et al., 2018).

Whilst conceptualising social class is challenging (Thompson, 2019), few would dispute the idea that children and young people from lower socio-economic backgrounds get less out of the education system than their more privileged peers (Reay, 2017; EEF, 2021). Despite the evidence of an attainment gap, the term social class is slippery. In a recent study of social attitudes by Heath and Bennett, almost 1/3 of the highest earners described themselves as working-class .

If social class isn’t just about money, what is it about? Sociologists have signposted that cultural factors are tied to social class backgrounds too (Bourdieu, 1984; Skeggs, 2004).

What is social mobility?

Social mobility describes how people can move up – or down – the social ladder, gaining – or losing – wealth and status as they do. It can be defined by the OED as “the ability or potential of individuals within a society to move between different social levels… or between different occupations.” There are two types of social mobility:

-

absolute mobility

-

relative mobility

Absolute mobility refers to an improvement in living standards for all, but with inequality gaps remaining consistent. Life is better for everyone, but some still have more than others. In contrast, relative mobility involves upwardly and downwardly mobile trajectories, with some individuals experiencing improved living standards and others facing declining living standards (Major and Machin, 2018). For one person to move up the ladder, another needs to move down to make room for them. In my research, I referred to these journeys up and down the ladder as social trajectories.

Aspirations and social class

The term ‘low aspirations’ is unfortunately used a lot in schools. It is associated with low-achieving groups of pupils and their families, particularly those who are working-class. This can lead to a deficit view becoming embedded, with academic pathways being viewed more positively than vocational ones. Young people then internalise this hierarchy, reading their own hopes and dreams as inferior.

My research proposed a view of working-class aspirations as potentially being different rather than deficient.

Young people’s aspirations are tied to the opportunities that are available to them. If society is unfair – and rates of social mobility are low – then altering young people’s hopes and dreams will not change this. We need to ensure fairer access to a wider range of opportunities and that cannot be the sole responsibility of teachers and leaders in schools. As teachers, we don’t necessarily get taught about the opportunities available to different children and young people in the communities that we serve. To help us to connect what goes on in school to the world outside of school, we can use the following processes:

1. Map-making

Rather than imagining one person on a ladder, it is helpful to imagine several people undertaking their own journeys across the same terrain. These people may have different starting points and different destinations. They may also have different resources to help them make their journeys. They will choose different paths from those available to them. My research suggested that sometimes teachers presume that all pupils are navigating the same maps as they did, forgetting that social class, place, gender, ethnicity, and other factors can affect pupils’ starting positions on the map and the resources available to them

2. Path-finding

Choosing which path to take can be challenging. Pupils need help to make informed decisions, based on the resources they currently have and those they might need to pick up along the way. My research found that female, working-class teenagers in a former coalmining town felt that they were expected to go to university but weren’t given support to decide what jobs this might lead to or information about what other opportunities might be available to them.

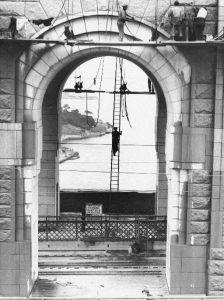

3. Bridge-building

Children and young people need resources to build the bridges that enable them to move along different pathways. However, their access to these resources is unequally patterned, based on social class, gender, ethnicity, place, and other social factors. Resources are also culturally specific and firmly rooted in local communities, which means that they don’t always work in the same way in different places.

For example, the resources we need for a journey through a snowscape might be different to those for a journey through a desert. Working-class pupils’ resources are likely to be tied to their starting points on the map. In sociology, these resources are called capitals and take three forms:

-

economic

-

cultural

-

social

(Bourdieu, 1986)

These resources can have significant effects on our journeys. If I have enough economic capital to travel by plane, then I will spend less time and energy than if I have to walk to the same destination. If I have a friend with a private jet, this social capital may help me to reach the same destination without even paying for a plane ticket.

Cultural capital is trickier to imagine, but still vitally important to the journeys our pupils undertake. Imagine that different people live in the different places we travel through. These different groups have different values and ideas about how we should live, but they all have their own forms of art, music, cuisine, philosophy, and religion. As I travel through these places, my cultural resources meet theirs. There will be similarities and differences, but also a hierarchy based on the power of the group in relation to other groups.

In our world, these cultural resources take three forms:

-

how I look, speak, and behave

-

the cultural objects I own

-

the qualifications I hold

Qualifications authenticate something important about who I am to other people. They ‘rubber stamp’ my knowledge and skills, as well as showing a place that I’ve already been on my journey: an educational institution. Both adults and children accrue these resources. Schools are key places where pupils gain cultural capital, but we also need to remember to value the cultural resources that children bring from home into school too.

Social capital describes the connections and relationships we have with other people. For children and young people, complex webs of social relations can introduce them to different lifestyles and job possibilities. Whilst we often consider the ways social capital supports people from privileged backgrounds in moving into elite professions (Friedman and Laurison, 2019), working-class communities may also offer local forms of social capital that give some children and young people status in the places where they live and learn.

Sketching the three forms of capital helps us to think about the resources that working-class young people gain in their families, communities, and schools.

We need to value their pre-existing resources by building on rather than replacing them.

What can this look like in school?

If teachers and leaders want to put these three processes into practice, the following strategies might be useful:

Map-making:

-

Scoping out local opportunities for education and careers

-

Understanding the employment patterns in the local area

-

Finding and celebrating the goodness in local communities

-

Understanding the starting points of our students and helping them to see a greater range of options and travel greater distances without feeling that they can’t come back (socially and geographically!)

Path-finding:

-

Ensuring curriculum alignment across key stages and schools – build from local strengths

-

Ensuring transition is effective, supportive, and positive

-

Tracing and celebrating former pupils’ journeys and making their pathways visible

-

Building meaningful links with educational institutions and prospective employers

-

Ensuring relevant staff are trained on the requirements and realities of particular pathways, so that they can advise students effectively and support if they have to adapt their plans

Bridge-building:

-

Building positive relationships with pupils, parents, and local communities as the foundation for high-quality education

-

Ensuring the curriculum builds bridges between pupils, their different cultures, and their social class backgrounds, rather than privileging one particular group

-

Using responsive teaching to build bridges between what pupils know and can do now and what they should know and do next to make progress

Map-making, path-finding, and bridge-building help educators to tie together the ‘big picture’ of children’s aspirations and social mobility with the day-to-day world of the classroom. These three processes help educators to identify and celebrate local opportunities and ‘small steps’ of social mobility, without stigmatising working-class young people.

Schools in ‘left behind’ communities often perceive their role as helping young people to learn to leave (Corbett, 2008). My decision to use a ‘bridge’ in the model emphasises that young people should have the choice to travel away from home if they want but should also have the option to stay or one day return. A well-built bridge is a permanent structure that connects one place to another. We’re far more likely to walk along a bridge to a new destination we’ve never visited before than to hitch a ride with a passing sailor who might not travel this way again. The aspiration to stay and succeed at home should be celebrated as much as moving away, even if local pathways do not involve further and higher education. Opportunities are about choices. Schools should not associate living in the local area as an example of failure. We should not stigmatise working-class communities or places in a bid to ‘inspire’ the working-class young people we serve.

In my work as Trust CPD Lead for L.E.A.D. Academy Trust, I am lucky enough to see fantastic examples of these processes in action across primary and secondary schools. I want to emphasise how much incredible work already goes on in schools. The map-making, path-finding, and bridge-building processes help us to contextualise these existing pedagogical approaches, curriculum decisions, careers education practices, and so much more within our mission to make the world a fairer, more equitable place. I hope that it supports you in reflecting on the work that already goes on in your setting, as well as inspiring some curiosity about your ever-changing local communities.

Our goals as educators are not to make working-class learners act like middle-class learners, but to build maps, paths, and bridges for all, recognising the individuality and intrinsic value of all the children and young people we serve.

References

Archer, L. et al. (2018) ‘The symbolic violence of setting: A Bourdieusian analysis of mixed methods data on secondary students’ views about setting’, British Educational Research Journal, 44(1), pp. 119–140. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3321.

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction: a social critique of the judgement of taste / Pierre Bourdieu ; translated by Richard Nice.: London: Harvard University Press ; Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Bourdieu, P. (1986) ‘The Forms of Capital’, in J. Richardson (ed.) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. New York: Greenwood Press, pp. 241–58.

Choudry, S. (2021) Equitable Education: What everyone working in education should know about closing the attainment gap for all pupils. 1st ed. Critical Publishing. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/nottingham/detail.action?docID=6621700 (Accessed: 26 January 2024).

Corbett, M. (2008) Learning to Leave: The Irony of Schooling in a Coastal Community. Halifax N.S.: Fernwood Publishing Co Ltd.

Friedman, S. and Laurison, D. (2019) The class ceiling: why it pays to be privileged / Sam Friedman and Daniel Laurison. Policy Press.

Major, L.E. and Briant, E. (2023) Equity in education: Levelling the playing field of learning – a practical guide for teachers. John Catt.

Major, L.E. and Machin, S. (2018) Social mobility: and its enemies / Lee Elliot Major and Stephen Machin. Pelican, an imprint of Penguin Books.

Reay, D. (2017) Miseducation. Bristol: Policy Press.

Skeggs, B. (2004) Class, self, culture / Beverley Skeggs. London: Routledge (Transformations).

Thompson, R. (2019) Education, Inequality and Social Class: Expansion and Stratification in Educational Opportunity. Oxon: Routledge.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply