June 26, 2019, by Rupert Knight

Life on the ‘tricky table’

In this month’s primary blog post, Catherine Gripton explores ‘ability’ grouping from a child’s perspective and asks whether children experience ‘ability’ grouping in the way we think they do.

To ‘ability’ group or not to ‘ability’ group?

There is much debate about ‘ability’ grouping with questions raised about effectiveness and concerns that it widens the attainment gap. Guidance published last year by University College London (UCL) provides a list of ‘dos and don’ts’ for attainment grouping, suggesting that there are many pitfalls to navigate when deciding how to group children in schools. Clearly, the impact of grouping structures depends very much on how they are used but research evidence, as described here, for example, shows that ‘ability’ grouping does not improve overall attainment and can actually lead to lower attainment.

‘Ability’ grouping is common practice

Most primary classrooms have some form of ‘ability’ grouping. These are more often grouping within the classroom although there is also a significant amount of ‘setting’ (movement of children between classrooms into ‘ability’ classes or groups). The most common pattern is to have four or five within-class ‘ability’ groups, partially the legacy of the primary national strategies, but uses vary from classroom to classroom. Some classes have one generic set of groups that are used for all teaching whilst others have several sets of groups, each used in the teaching of a specific subject (e.g. maths groups, phonics groups). The groups can also be quite fluid (and sometimes include self-selection) or can be more fixed with group names and a seating plan.

Children’s understanding of ‘ability’ grouping is mixed

When asked, teachers say that they tend to use ‘ability’ grouping to meet children’s needs but it is interesting to consider whether children feel that it does. Do they know that the groups they are working in are determined by ‘ability’? What do they think ‘ability’ is? Do older children understand this differently to younger children?

Some research has focused on children’s awareness of groups, as summarised in this article by Rachel Marks.

My own research on children’s everyday experiences of ‘ability’ in Key Stage One classrooms suggests that children’s understanding of ‘ability’ grouping is mixed. An investigation into this in two classrooms showed that children’s experiences were highly varied with a broad range of factors shaping their experiences. These factors included:

-

which groups their friends were in

-

whether they equated being clever with being well-behaved

-

how much they paid attention to the adults in the classroom and what they were doing

-

their preferences in terms of group size and table location within the classroom

-

the tasks they were given and whether they felt that different children were given different tasks

-

how much they noticed differentiated resources such as reading scheme or book band levels

From this research, it was clear that the teachers saw the groups as quite changeable but the children mostly viewed them as fixed. Some of the children appeared to be unaware of the groupings in their classes whereas other children seemed very aware. In the words of six-year-old Rachel:

“I am at the stage that’s harder than Yellow table. So, Red group’s the tricky table and Yellow isn’t that tricky. If I went on Yellow table and I did twenty when I was meant to do a hundred work I would find it really really easy.”

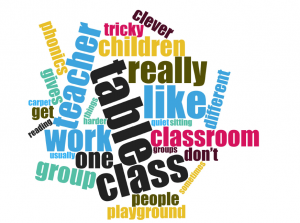

Her understanding of the grouping and the tasks that she does in class have begun to shape her view of herself and others. She went on to explain that, “I am quite clever! I‘ve got a really clever Mum and a really clever Dad and a really clever brother”. There is a suggestion, here, that she is beginning to form an understanding of cleverness as something that is inherited. Rachel also created a word cloud:

Jasmin, aged seven years, used the letters A, B and C to describe ‘ability’ (high, middle and low). She explained that where you sit depends on how good you are at maths or English:

“So if they think you are… um… like the second…well B, yeah B, you would be on my table. It is how clever you are at maths or English.”

Jasmin was clear that this is not the same for other subjects. In PE, she felt that children were grouped according to how sensible they could be and for Art you would be able to sit with anyone. She seems to be viewing ‘ability’ as three tier in maths and English specifically, based upon her interpretation of her experiences.

What are your feelings about ‘ability’ grouping?

What messages do you think individual children take from the grouping practices in classrooms and why have they formed these ideas? We would love to know what your experiences and thoughts are.

Our school has ability groupings in phonics so that children move onto and work at the right stage of recognising sounds, blending etc. I have tried, as an NQT in Year 1, to have mixed pairs on the carpet and more recently taught the whole class with the same pairs at tables I.e. alien descriptions where secure/greater depth writers are paired with emerging/developing/EAL who need support to write sentences on whiteboards. However for maths small groups, we naturally formed 4 ability groups and I now wonder whether the ‘levels’ of higher to lower has become even wider because of this. It is a hard balance to strike, especially when teaching such a broad spectrum of learners like I have this year. Next year, I will try some lessons with mixed absolutely partners and see if it helps progress.

I remember as a recently qualified teacher being frustrated and not a little annoyed that the Deputy head with whom I worked would not agree with me that we should ability-set our pupils for maths and English. To me it seemed a no-brainer that teaching would be easier and that pupils would make more progress because the teaching would be so much better matched to their needs. It is almost counter intuitive to do anything else – try explaining to anyone outside education why you might actually choose to teach without ability grouping.

My experience has been that a thoughtfully planned mixed ability lesson will lead to better all round progress every time – low threshold / high challenge tasks are especially effective but simply giving learners a choice of their starting point can also work well once pupils have developed suitable self-regulation skills.

In my view there are a number of reasons for this but high among them is the notion that learning is significantly impacted by our emotions and whilst we can be over-whelmed by challenge, being predetermined is far more likely to put a ceiling on achievement