May 3, 2017, by Rupert Knight

What do we mean by ‘Character Education’?

The use of ‘Character Education’ as a term has become more widespread in recent years but can be understood in many different ways. In this post, Rupert Knight explores this concept and provides an example of one school’s approach.

Education for character as well as academic attainment is nothing new and the 2015 report from Demos, the cross-party think tank, points to its origins in many related initiatives, including an explicit mention in the historic 1944 Education Act. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that character has become a higher profile issue, with Character Awards being introduced by the government in 2015. The dangers, however, of character education being misinterpreted or becoming just another educational fad are acknowledged by some of the very people cited by the DfE, as summed up in this article.

Perhaps, then, we should take a step back and start by questioning what character education might mean and comprise. The University of Birmingham’s Jubilee Centre, specialising in research in this field, offers a definition based on ‘moral education focused on developing virtues as stable qualities of character’. These virtues are classified as moral, civic, intellectual and performance. Meanwhile, a quick glance at the DfE’s 2016 Character Award winners shows recognition of a diverse range of attributes, from what might be termed learning behaviours to broader life skills and work with local or global communities.

Of course, schools seeking to educate the whole child and look beyond purely academic notions of achievement is nothing new. The work of Martin Seligmann and colleagues in the US on character strengths and virtues argues that almost all cultures have long shared six common virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity, transcendence, justice and moderation and most schools would surely claim to foster these qualities in one form or another.

With all this in mind, how might schools develop a clear stance on this issue?

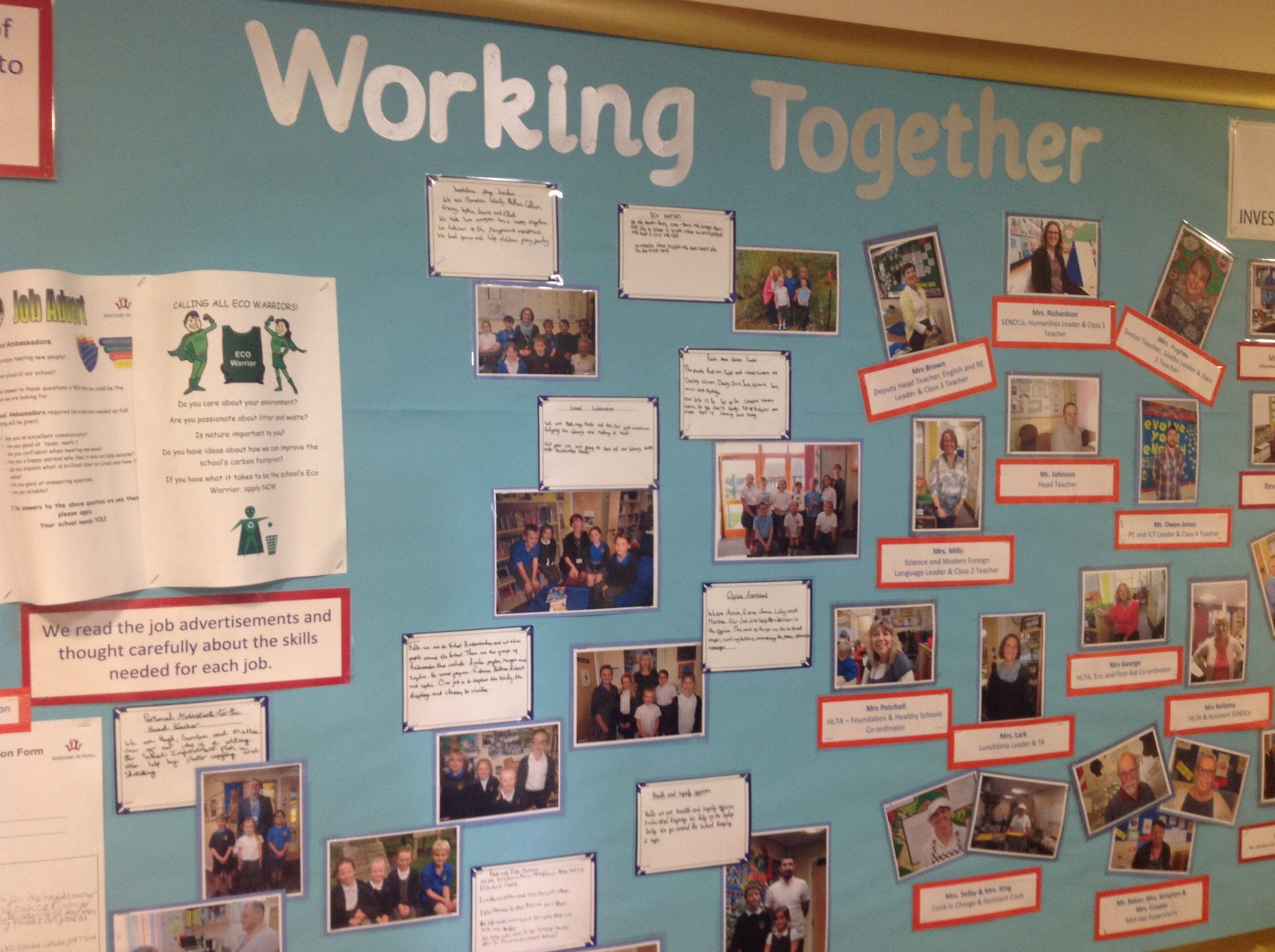

It may be instructive to look at one particular case at this point. Langar C of E Primary School in Nottinghamshire is a school with a strong vision for character education, developed and refined as a staff team.

Langar’s model is depicted as a trinity of interdependent qualities, which retains a very clear focus on the academic:

The trinity representation

As well as the acknowledgement of academic excellence and learning skills, it is notable that, as a faith school, its ‘values’ component is heavily influenced by five Christian values, carefully distilled from a much longer list.

Five values: care, respect, fairness, love and thoughtfulness

Five learning skills: independent enquirers, reflective learners, creative thinkers, self-managers, team workers

Perhaps most striking however, is the way that Langar’s character model pervades every aspect of the school. The trinity image is to be found in every classroom and the ethos is reinforced through displays and pupils’ ‘recognition charts’:

‘Take Care’ display

Learning to Learn recognition chart

The five values provide half termly focus points and are reflected verbally in teachers’ interactions with pupils and parents. Significantly, therefore, this trinity model offers staff, pupils and parents a shared understanding and language. In the regular celebration service, for example, pupils are able to explain their achievements in more specific terms by referring to these hallmarks.

Deputy Head Emily Brown explains the school’s vision further:

The National Academy of Sciences in the US, in a 2016 report, concluded that educational organizations need to define for themselves, in a collaborative way, their own character goals and to specify what each attribute will look like. In line with this, it is clear from Langar’s example that a bespoke, coherent and consistent vision across a school has been at the heart of their approach to character education. Building such a vision, however, might raise some questions for schools, such as the following:

- To what extent should such values be modelled and explicitly taught, as opposed to being infused more subtly through the school?

- Should schools try to evaluate the impact of character education (and, if so, how?) or is this something to be resisted? How should this be reflected in inspections, for example?

- Is there a way of promoting and capturing progression in character development?

Such a role for schools and teachers is not without its critics. Some have argued against a perceived rise of ‘theraputic education’ as a harmful distraction from subject-related academic content. Perhaps the term ‘character education’ is also unhelpful, implying some insidious form of mind control.

Whatever we choose to call it, however, it seems to me that at the heart of a strong vision for developing personal virtues and attributes is the opportunity to reclaim much of the powerful ‘hidden curriculum’ work that schools have always done (see for example recent research on the impact of Philosophy for Children). In recent years, alongside a proliferation of sometimes dubious learning styles ideas, there may also be a sense that character has come to be narrowly identified, in England at least, with the government’s promotion of ‘Fundamental British Values’. As exemplified at Langar, it is possible for schools to approach character education as a unique and constructive response to a school’s position in a distinctive local community.

What are your views and experiences? Please share a comment.

Character education goes beyond academic success and looks at educating the child as a whole. During our immersion day we were introduced to the growth mindset approach, which focuses on developing a positive attitude to learning, and being respectful to others. Teachers praise children when they see values such as independence, perseverance and effort to ingrain this into the classroom culture.

We visited Langar Primary school and observed the character education ideas in place. The ethos of the school was very well implemented throughout each of the classrooms and the children seemed to be knowledgeable about the values and use them in everyday life- taking them home as well as in their learning.

A thought-provoking, informative and balanced evaluation about Character Education.

As a group we spent half a day at Langar CofE Primary School. The Executive Head highlighted that their model wouldn’t necessarily suit other schools and how important it would be to implement Character Education as a whole school initiative, embedded into the ethos which both staff and students invest in wholeheartedly. To be effective it would need to be adapted to suit the particular needs of the school and their children. Those wishing to implement a character education schematic need to be aware that some pupils, most notably HA girls in the instance we observed, may show resistance and need careful handling.

Interestingly, The Learning Trinity at Langar used a bottom up approach which gave the potential for children to develop to a much higher level than Year 6 Expected. Besides Phonics sessions, all other subjects were taught in mixed ability groups. The Learning To Learn Recognition Chart had moved away from attainment recognition to celebrate a pupil’s Learning Journey, where progress at their own level was celebrated rather than i.e. focusing on the children who produced the neatest work.

Students at Langar seemed to have such a good understanding of the values and Trinity etc, and how it was all helping them to learn. Pupils understood the importance of developing the values evenly rather than just collecting stickers as quickly as possible for one element in order to fill a chart. They could see the benefit to their own learning. Although they articulated the different elements very clearly we did question whether this was actually embedded so they would take it forward positively into secondary school and their adult life.

We therefore thought it would be useful to follow up with previous pupils in Year 7, 8, 9 etc, to see how well children had managed in KS3. Although there are a lot of different things that could impact on their future success, would Langer’s children be better adapted to manage challenges in Secondary? Especially considering that in this instance the two main secondary options are either a grammar school, with 11+ exam entry, or a large comprehensive secondary, which used streaming with a major focus on exam results. With regards the transition to Secondary, we could see how pupils might become ‘good learners’ by the end of Year 6 so that they can work in an environment even with weaker teaching. They’ll have the comprehension ability and other skills to gather the useful information delivered to them and use it effectively. It would be interesting to find out how pupils copied with assimilating into the new school environment and whether any of their Trinity Learning Skills are maintained or lost, depending on many factors including what is happening in the individual child’s life.

It would have been useful for our group to have seen first hand how children worked together and how the teacher utilised the scheme i.e. teaching skills rather than continuing to repeat topics until they were secure. However, as student teachers we could identify which aspects of Langar’s approach could be adopted into our own practice, on a smaller scale. On a larger scale, a school would need to develop their own approach with caution to make sure the Character Education idea isn’t misused or misinterpreted.

I love this article it is so interesting, I also blog on primary education in Nigeria

Its is besd approach as well as the acknowledgment of academic excellence and learning skills. I will discuss it with https://qanda.typicalstudent.org team members. Once again thank you so much.

very good article we work in the field of medical training for doctors and I think there are certainly some application example for us hereby warm regards https://www.medcram.de/cme