April 14, 2013, by Brigitte Nerlich

Making the planet public

I have always wanted to make a link between ISS – the Institute for Science and Society at the University of Nottingham – and ISS – the International Space Station – in OUTER SPACE. When looking yesterday at a picture of a cloud vortex taken by Commander Chris Hadfield from a window of the ISS, the link came to me (and I know it’s a specious one, but I just ran with it). We, at ISS, study public engagement with science and science communication. Chris Hadfield, at the ISS, engages the public with science, technology and, most importantly, the planet. I am interested in the way verbal and visual images change the way we see the world, engage with it and act on it; Commander Hadfield, tweets images that might very well change the way we see the world and engage with it.

Space, photography and social media

Commander Hadfield is “a Canadian Astronaut, currently living in space aboard ISS as Commander of Expedition 35”. More information about his mission and his work can be found on this recent blog by Sara Hamil. He has become famous because he tweets images of our planet Earth taken from the international space station. The tradition of taking images of earth began with Earthrise.“the name given to a photograph of the Earth that was taken by astronaut William Anders in 1968 during the Apollo 8 mission”, in 1968. Earthrise became famous, not only because it was a beautiful image, but also because it transformed the way we humans see the planet that we inhabit and ourselves. It was, in some sense, a visual Copernican revolution. Some attribute the beginning of the environmental movement to this image.

‘Earthrise’ took a while to reach us humans on earth. Now things are very different. @Cmdr_Hadfield tweets his pictures directly to the public. They can be viewed on his twitter stream and on his face book page. They can be retweeted and they circulate widely in cyberspace. Whether, like Earthrise, they will contribute to seeing the world differently will have to be seen. Some think looking (vicariously) back down to earth gives us ‘perspective’ and may give us a new sense of self and others, called the ‘overview effect’…

The global and the local; beauty and the beast

Similar to Earthrise, Chris Hadfield’s images show us our planet in all its majestic beauty and make us aware of its fragility. However, they also provide more intimate glimpses of local geography and local structures which are reported with some pride by those pictured. Here the Scotsman reports on images taken of Scotland; here itsliverpool.com shows an image of Liverpool taken from space. The global becomes local, and therefore perhaps not only a matter of beauty but also a matter of concern.

These images also demonstrate very clearly how we ‘geoengineer’ our planet. This, for example, is an image of engineered agriculture. Many pictures show the sprawl of cities and the energy/light they emit into space. There are also images of extreme weather events which may or may not be due to climate change, such as these ones of the Queensland floods at the beginning of this year. All these images are paradoxically beautiful.

Science, technology, art and… windows

Chris Hadfield said in one of his tweets: “I’m not all that artistic, but I appreciate it when others are.” The tweet is accompanied by this picture of a cityscape which looks like modern art. Chris Hadfield may not be artistic, but this picture, like so many other images produced by scientists visualising the otherwise invisible, bridges the domains of art, science and technology. Myriad technologies are obviously involved in bringing these artistic images down to earth. They all depend however on one superficially rather mundane one: a window.

Images from the ISS can only be taken because the space station now has a new type of panoramic window, called a cupola window (here you can see Chris Hadfield in the window). It is “named after the observation decks that old-time train cabooses had” and includes “six side windows and a big one in the center.” Here the spectacular, in every sense of the word, meets the relatively mundane: windows (and glass, about which I have written a blog post a while ago). Glass and windows help to make the invisible visible. They are a both a product and a tool to look at human civilisation, its achievements and its dangers. They are also an important medium of science communication.

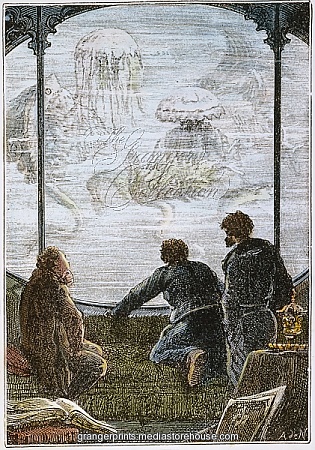

The ISS and the Nautilus: windows and wonder

The cupola window reminded me of the viewing bay on the Nautilus, the fictional submarine whose commander was Captain Nemo. In his novel 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (French edition, 1869-70) Jules Verne steered the Nautilus through the space of the Earth’s oceans. He made the oceans and their fauna and flora visible to all those who read his novel and admired the illustrations crafted by Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou. The illustrations that litter Verne’s novels (mostly ), like the digital images sent back from space via twitter, evoke a sense of wonder at the beauty of the earth we inhabit, which is a pre-requisite to engagement and, perhaps, concern.

Commander Hadfield stands in a long tradition of (real and fictional) pioneers who make our planet public. They use science and technology from submarines and space stations and from woodblock engravings, chromolithographs, and chromotypographs to digital photography and twitter to engage us with the world.

Post-script

Video of Commander Hadfield’s reflections on his mission before returning to Earth on Monday 13 May, 2013

Space Oddity by David Bowie recorded on ISS by Commander Hadfield

And more

Added, 10 June, 2013: Picture of picture of NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy taking a picture through the cupola. (HT @pourmecoffee and @trueanomalies)

Images:

The International Space Station, Wikimedia Commons

Professor Aronnax, the Canadian master harpoonist Ned Land and Professor Aronnax’s faithful assistant Conseil look at jelly fish through the observation window of the Nautilus (as coloured print)

[…] Look for example at these beautiful pictures of earth from space and appreciate their beauty (and the images tweeted by Chris Hadfield). The images that Curiosity is beaming down are beautiful too. They should remind us, however, of […]

[…] is a snowclone. And, in fact, I myself have often used it to generate snowclones, such as “Making the planet public”, “Making thoughts public”, “Making plants science”, “Making science songs” and so […]

[…] of Babel beginning to be built around the world knowledge, on wonder, on antibiotic resistance, on Hadfield’s images of our planet from the ISS, on epigenetics, on responsible innovation and the invisible hand process, on making science public […]

[…] When we look back now at the novels and their illustrations, it feels like exploring a museum of our technoscientific imagination. The people, landscapes, technologies, animals and objects contained in this quaint museum are illuminated by a large variety of light sources, from the sun to the moon, from gas and electric light to the northern lights and the ‘green ray’. The novels make the ideal of scientific ‘enlightenment’ real and public and bring science, technology and exploration to new ‘publics’, indeed directly into their homes. They make the invisible and inaccessible visible and accessible, a tradition continued today from space. […]