July 6, 2012, by Sean Matthews

Return of the Civilizing Mission

At the recent Observatory on Borderless Higher Education ‘Global Forum’ in Kuala Lumpur, ‘New Players and New Directions: The Challenges of International Branch Campus management’, there was much to digest about current thinking concerning Transnational Education. The delegate list itself was something of an internationalisation ‘Who’s Who’, and the programme offered a rich set of presentations – including one from Nottingham’s own Chris Ennew, accompanied by students from the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus – about all aspects of the international branch campus experience.

At the recent Observatory on Borderless Higher Education ‘Global Forum’ in Kuala Lumpur, ‘New Players and New Directions: The Challenges of International Branch Campus management’, there was much to digest about current thinking concerning Transnational Education. The delegate list itself was something of an internationalisation ‘Who’s Who’, and the programme offered a rich set of presentations – including one from Nottingham’s own Chris Ennew, accompanied by students from the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus – about all aspects of the international branch campus experience.

As with my reactions to Dzulkifli Abdul Razak a few weeks back, I found myself nodding vigorously in agreement with one presentation in particular, ‘Is small really beautiful? The place and value of “niche” campuses’, given by Professor Michael Worton (Vice-Provost, International, University College London). At the same time, however, just as with Professor Dzulkifli’s talk, I was troubled by a quite fundamental anxiety about the argument which was being made, which seemed, even whilst giving a welcome and unusually forceful call to ethical practice in cross-border education, to encapsulate a central flaw in the rhetoric and practice of our current modes of internationalisation.

First the agreement, the nodding, the applause. Professor Worton offered a bold rebuttal to the earlier argument, by Professor Raj Gill of Middlesex University – that internationalisation strategy must be driven above all by financial concerns, that developing a sustainable finance model was the key to success. Worton was adamant that financial imperatives must be second to academic mission in any transnational education activity. A University’s internationalisation strategy, he argued, must be conceived as an extension of the institution’s basic mission, it must place at its heart that institution’s ‘core values’. Those values, he stressed, should involve an ethical and humane relation to the world, a sense of profound responsibility towards mankind, and a recognition of the high function and role of the University. A short presentation about Global Citizenship, available on YouTube, confirms just how strongly this ideal underpins his understanding of UCL’s position.

In UCL’s case those values are, of course, self-evidently associated with research of the highest quality, excellence in teaching, and the commitment to producing world-leading and fundamental contributions to knowledge. In any of the key ranking tables, UCL is a World Top 10 institution. In order to deliver overseas operations consistent with these ideals, UCL has concentrated on delivering precisely targeted, ‘niche’ programmes. These are predominantly postgraduate, and respond to the specific needs and demands of carefully selected local partners. In Qatar, for example, Masters courses in museology, archaeology and cultural heritage management are calculated not merely to build capacity in the field, but actively to create, ab initio, a heritage industry within the state, thereby supporting and influencing the government’s nation-building processes.

But Professor Worton went beyond such relatively conventional, even uncontroversial goals, to add a further, defining quality to UCL’s mission. In this he was quite startlingly, boldy explicit. UCL’s purpose, he insisted, is also to drive social or political change in those places of the world where their programmes are placed. UCL’s objective is, quite literally, to contribute to making the world a better place. Three times in fifteen minutes he reiterated UCL’s ‘responsibility’ to ‘make change’, to ‘bring change’, to ‘change the way other countries operate’. And this was not merely in terms of building better bridges or developing sustainable agricultural policy, things we might consider the proper matter of academic disciplines. He stressed, rather, the outreach and public engagement elements of UCL’s function. In the case of Qatar, he explained how their engagement with the regime also involved the demand – to which the Emir acceded – to be permitted to work with marginalized and alienated communities in the state, most notably with the prison population, which is famously and overwhelmingly made up of non-Qataris. Worton reiterated that UCL’s internationalisation is grounded in a fundamentally ‘ethical’ position, a position it is able to take, in no small part, as a result of its niche position (and the ease with which it can, if necessary, walk away), and of course as a result of its reputation and status, which do indeed permit the institution to dictate the terms, and the prices (financial, as well as in terms of support for outreach and CSR work), of its transnational projects.

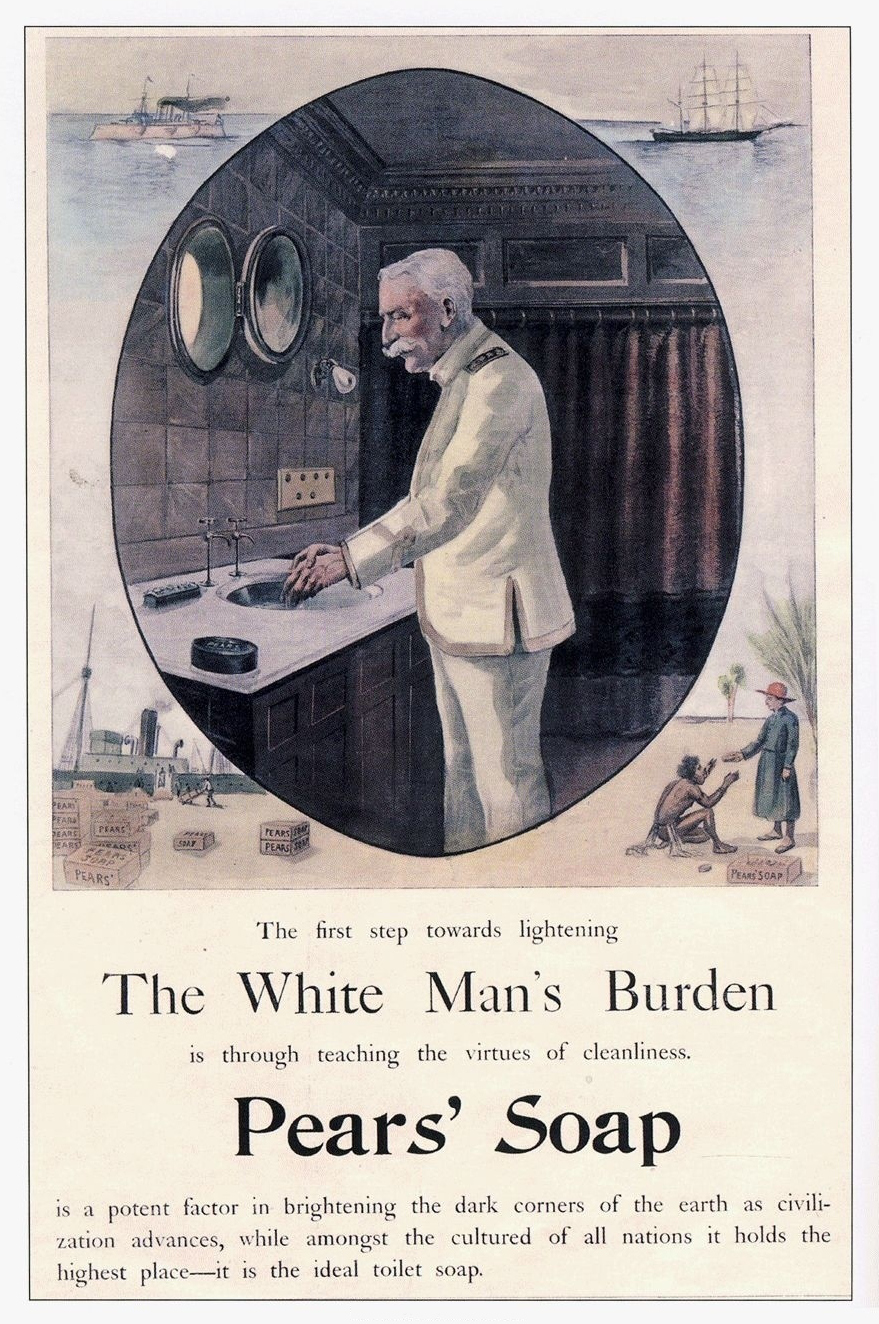

What was striking about this presentation, and this is where my reservations begin, was something that Professor Worton himself, playfully and self-deprecatingly, characterized in passing as ‘hubris’. His meaning was clear: he holds his colleagues and institution to a high ethical standard, and he believes passionately in what he is doing, and he realises that he might sound a little arrogant in insisting on UCL’s virtues. But this very conviction that it was for UCL to deliver change, to ‘bring competition’ to the HE markets of the world, to set and raise global standards, surely also betokens a really rather remarkable confidence in the demonstrable rightness of UCL’s – and Michael Worton’s – values and priorities. I agree that we should not, as he put it, ‘fetishize Said’, and I am as weary as next sahib of the easy banality of equating any and all overseas educational activity as ‘neo-colonial’. And it’s also only fair to admit that in a fifteen minute presentation there is little space to develop an account of the dialogic and collaborative aspects of UCL’s mission, but nonetheless the message he delivered about UCL’s strategy was that the direction of transmission, the mode of production of knowledge, primarily involves the UK’s finest bringing enlightenment to the dark places of the earth.

Professor Worton would doubtless bridle at that last sentence, and with good cause: UCL have genuinely done remarkable things to make the world a better place, and it would be churlish to denigrate either their achievements, or his own good faith – he is a breath of fresh ethical air in what can often be a decidedly murky environment. But as I reflect on his talk, and indeed all the talk I heard at the forum, I realise that none of the speakers, and not one of these many institutions, has come to internationalisation because, as a priority and point of departure, as a defining element of their mission, they want to ‘make change’ to themselves, to ‘bring change’ to our own institutions and culture, to ‘change the way we ourselves operate’. No-one seems to have started from the position that being involved in transnational education might be undertaken, ahead of any other consideration, in order to improve, to enhance, or to change our own practices.

Internationalisation, where it is not an inherent, an unquestioned or a talismanic and self-evident good, is certainly acknowledged to be a process which, incidentally and almost inadvertently, does effect change ‘at home’. For some institutions, indeed, such change is actually perceived as a problem, a threat to and dilution of the core mission, the original qualities of the place. What does it suggest about internationalisation in our time that the strongest expression of the principles of an ethical educational engagement and of our humane responsibility, is in practice grounded in such monumental self-assurance? Can we really be confident that our current phase of cross-border education is so very different from the ‘civilizing mission’ of our predecessors?

Dr Sean Matthews is currently seconded from the UK as Director of Studies in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply