October 12, 2016, by Stephen Legg

Remembering a Democratic Legacy of the Great War in Interwar India

In 2019, India will embark upon a uniquely postcolonial set of centenaries. During the Great War the Defence of India Act (1915) had given the Government of India exceptional powers to silence dissent and crush any nascent “terrorist” or “revolutionary” movement. So effective had the powers proven, against both radical and moderate nationalists, that there were many within the colonial state who sought their extension into peace time. The “Rowlatt” (Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes) Act of 1919 attempted this, and the resistance against the act was led by the ex-lawyer and future-Mahatma, Mr MK Gandhi. The centenary of the Rowlatt “Satyagraha” (the name for Gandhi’s non-violent, political “truth-force”, protest movement) will doubtless be commemorated by the Congress party and many others in India.

Yet both these commemorations may well be overshadowed in 2019 by the centenary of the “Jallianwala Bagh” massacre, in which the colonial state displayed the violence inherent in the Rowlatt regulations in Amritsar; the shooting of unarmed civilians that sparked a global outcry. While India was enduring violence at home it was plotting peace abroad. The year 1919 will also mark the centenary of India’s contribution to the Peace Treaty of Versailles. Few anticipated that India’s attendance at the conference would automatically make it a founder of the League of Nations, the only non-self-governing state to ever become a member. 1919 will be a busy year for centenaries; all of the above, in some way, are legacies of the First World War.

Who, then, will have time to commemorate the Government of India Act of 1919?

It lacks glamour or tragedy, but its legacy was as profound as the founding of Congress’s anti-colonial nationalist mass movement. It, too, was a legacy of the First World War, which had forced the British Secretary of State for India to acknowledge nationalist demands for political progress. In 1917 Edwin Montagu made a declaration acknowledging “responsible government” as the goal of the British in India. While the term was intentionally vague, Montagu made good on his promise, touring India to assess local opinion in 1917, and co-authoring with the Viceroy of India the 1918 Montagu-Chelmsford report, which laid the foundations for the Government of India Act (1919). This, while not providing a constitution, was acknowledged as a constitutional reform of historical proportions.

Between the declaration of 1917 and the Act of 1919 there had been feverish debate in Britain and in India within liberal and conservative circles regarding what responsible government was and which steps toward it would be taken. Britain at that time had no intention of giving up its autocratic control over India, yet it was now committed to introducing democratic reforms. The well-qualified but slightly improbable figure who provided the solution to this dilemma was Lionel Curtis, and the solution was that of “dyarchy”.

Dyarchy was a re-imagination of the structure of the state in India, and of the way that the subjects of governance were administered through that state. Many powers that had been centralised were devolved to “provincial governments” (many of which had larger areas, populations and incomes than fully-fledged European states), and at the provincial level the subjects of governance were divided between those that would be “reserved” for Governors and their staff, and those that would be “transferred”, to be administered by elected Indian Ministers and their staff. The province thus emerged as a geographical solution to how democracy could be introduced, preserving colonial autocracy at the centre of the state and the centre of each province.

Dyarchy was, by common consent, a miserable political failure. Congress refused to seek election or cooperate with the provincial legislatures for much of the 1920s. The artificial divisions of subjects into reserved or transferred created unworkable barriers within provincial governments, while the system itself was stacked so as to secure the colonial state against effective opposition at the provincial level and to deny elected ministers authentic training in the arts of democratic governance.

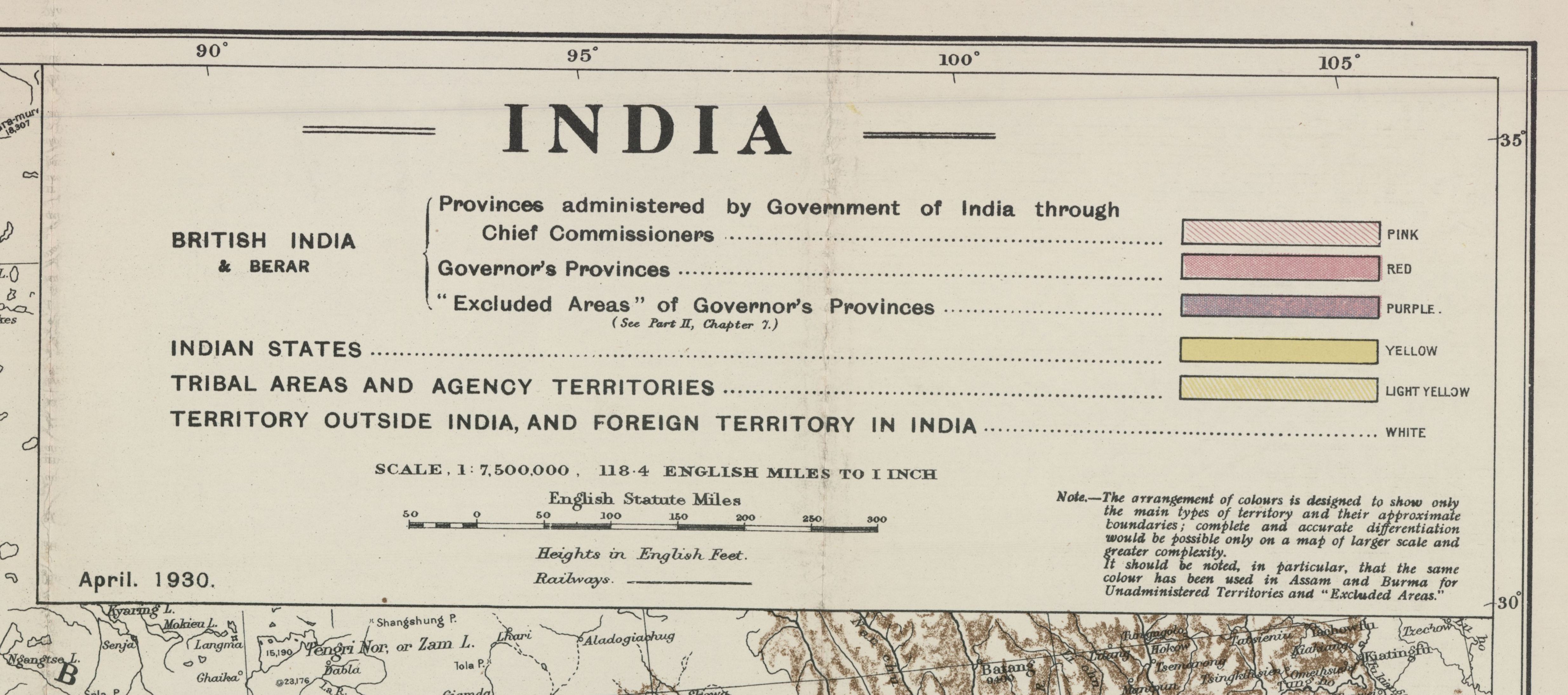

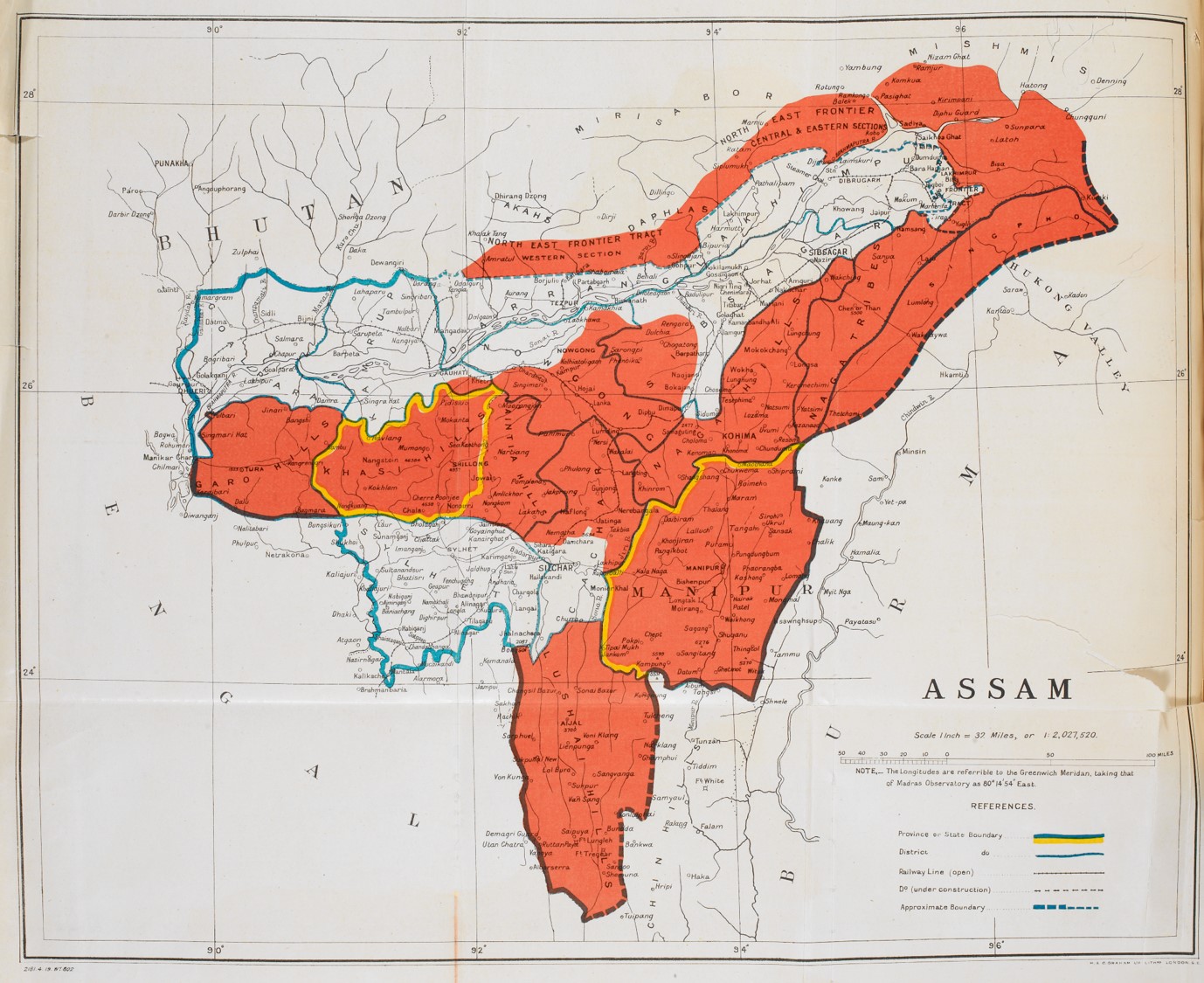

Despite its failings, dyarchy has much to teach us about the politics of the interwar period. Though it was a national system embodied in an act for the Government of India, this Act was passed in London and was based on an idea devised by an international network of imperial federalists. The re-structuring of the colonial state was informed by an imagination of horizontal and vertical grids with lines of transferral and devolution that could not be crossed. These fortifications were there to defend the autocracy of the state, but there were also “excluded areas” of the country that were protected from the ravages of democracy due to the presumed under-development of their inhabitants.

Such areas were explicitly presented as being backward (with most of Assam being exluded), while the provinces were presented as experimental spaces in which a potential, democratic, responsible Indian future was tentatively brought into restrained being.

We should therefore take the production of scale seriously. This means exploring the international networks that brought nations and regions into being; acknowledging the significance of naming a person, place or event as “local” or “imperial”; and of questioning that naturalness of scales such as the local, regional, national, imperial or international, which dyarchy showed to be inseparably networked together and extremely malleable political concepts. While extensively reworked, dyarchy laid the foundations for the “responsible government with safeguards” model of federal India embodied in the Government of India Act (1935), much of which transferred seamlessly into the Constitution of Independent India (1950). Perhaps it may be worth a centenary after all.

This piece is based upon Stephen Legg’s 2016 article, ‘Dyarchy: Democracy, Autocracy, and the Scalar Sovereignty of Interwar India’, which was published in the journal Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply