November 1, 2019, by Benjamin Thorpe

Reading group: Handbooks of Conference Diplomacy

- Ernest Satow, International Congresses (London: H.M. Stationary Office; 1920)

- Maurice Hankey, “Diplomacy by Conference”, paper read at British Institute of International Affairs on 2 November 1920, printed in The Round Table: A Quarterly Review of the politics of the British Empire XI (1920-1921), pp. 287-311

- Johan Kaufmann, Conference Diplomacy: an introductory analysis (Leyden: A.W. Sijthoff / Dobbs Ferry, NY: Oceana Publications; 1968)

- A.J.R. Groom, “Conference Diplomacy”, in Andrew F. Cooper, Jorge Heine & Ramesh Thakur (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (Oxford: OUP; 2013), pp. 263-277

For the first reading group of the new academic year, we pulled focus on a literature that we had previously danced around, but which could not be more germane to the project aims: those texts that have tried to define and categorise the field of ‘conference diplomacy’ in various periods. This often quite technical literature on how to conduct diplomacy by conference is revealing both for what it reveals of how the practice of diplomacy-by-conference was thought of by the writers, and for how it conjures ‘conference diplomacy’ into being as a coherent concept and a literature.

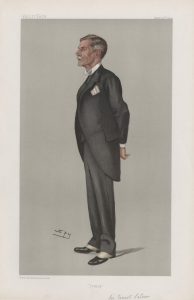

Sir Ernest Mason Satow (‘Men of the Day. No. 875. “Peking”‘) by Sir Leslie Ward. Chromolithograph, published in Vanity Fair, 23 April 1903. NPG D45167 © National Portrait Gallery, London

The major touchstone for this literature, as for the practice of diplomacy in general, is Ernest Satow. Following a long diplomatic career, mostly spent in the Far East, Satow – frustrated in his ambitions for an ambassadorship – turned his mind to a scholarly examination of diplomacy. His Guide to Diplomatic Practice was published in 1917 and swiftly became definitive, becoming familiarly known simply as “Satow”. Around the same time, he was commissioned by the Foreign Office to write a historical ‘handbook’ on international conferences, for use by British delegates at the Paris Peace Conference.

The resulting handbook, International Congresses, constitutes an attempt to pull together the threads of how diplomatic congresses and conferences (Satow, influentially, saw ‘no essential difference’ between the two) operated. Previously organized in an ad hoc and context-driven manner, Satow sought to extrapolate rules of best practice by which such conferences ought to be run. He did so with reference to fourteen such events, covering the century from the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) to the Conference of Bucharest (1913), and asking of each questions of their location, circumstances, and details of their organisation and conduct.

Maurice Hankey strolling with his pipe, 1921. Unknown photographer, black-and-white photograph. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-npcc-05489, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/npc2007005487/

In 1920, the same year in which Satow’s handbook was publicly published, Maurice Hankey gave a paper at the British Institute of International Affairs in which he surveyed the more recent history of conference diplomacy, particularly the 488 conferences he had personally been involved in since 1914. Hankey spoke not from the position of a diplomat, but that of an experienced conference secretary: he compared his position to that of a wicket-keeper, which he modestly interpreted as meaning that he had ‘seen a great deal of the game’. Unencumbered by the systematic history through which Satow developed his prescriptions, Hankey emphasised instead the way in which conferences enabled the development of intimacy and friendship, and the importance of ‘the social side’ in fostering these elements. Though his material was drawn from wartime conferences, Hankey expressed the strong hope that future wars might be averted by ‘the judicious development of diplomacy by conference’.

Johan Kaufmann presiding at a UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) conference, 1974 © UN Photo/Teddy Chen

Half a century of sustained growth in international conferencing later, another scholar-diplomat, Johan Kaufmann, wrote a new handbook aiming to pass on ‘the practical details of international conferences’ to a new generation of diplomats. His book, Conference Diplomacy: an introductory analysis, was first published in 1968, with revised editions in 1988 and 1996. Kaufmann combined Satow’s predilection for extensive categorisations with Hankey’s attention to the para-conference goings on, from informal encounters to conference restaurants to the influence of good organisation on the working atmosphere. He paid particular attention to the spatialities of conferencing, from the physical layout of rooms and tables to ‘geo-climatological’ factors like room temperatures or the familiarity (or unfamiliarity) of conference locations.

Another half-century on, the very fact that ‘conference diplomacy’ is still afforded its own editorial space in the mammoth, almost thousand-page Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (2013) is noteworthy. While other chapters were commissioned to cover ostensibly similar subject matters like ‘multilateral diplomacy’, ‘commission diplomacy’ and ‘institutionalised summitry’, the editors evidently still considered ‘conference diplomacy’ distinct enough to warrant its own chapter, in this case written by John Groom. Groom studiously tips his hat to the century of literature on conference diplomacy, and gives a sense of the ordered messiness of conferencing, balancing logistical factors like procuring rooms and establishing secure wireless connections with human factors like friendship, and fatigue. His larger argument is that ‘global problems’ that touch every inhabitant of the planet – he focuses on environmental issues – are a driver for a new form of ‘global conference’. However new this development really is, it is clear that the literature of conference diplomacy is far from obsolete.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply