May 1, 2018, by Stephen Legg

Geographies of Sensory Politics: Re-thinking Atmospheres

Geographies of Sensory Politics: Re-thinking Atmospheres

Session at the New Orleans Association of American Geographers Conference, April 10th 2018

One of our broader objectives in “Conferencing the International” is to conceive of conferences as multi-sensory spaces and to question the extent to which we can explore sensory geographies of the past and their impact on international politics. This session afforded an opportunity to discuss the challenges in this and similar tasks, assembling five speakers from within and beyond the geographical discipline. We opened with Ivan Marković’s paper “Sensing past atmospheres; a green silk kimono and the sensory politics of smoking c.1880 – 1930”. The paper contrasted the gendered geographies of smoking in pre-1914 England, contrasting female and furtive attempts to eradicate the traces and smells of smoking with the male, domesticated and leisurely luxury of the “smoking room”. These spaces were a staple sector of the bourgeois home, variously austere, Orientalist (the presumed interior to complement a slower, more sensuous practice). As smoking became more common as a result of changing social norms and the mass production of cheaper cigarettes the domestic smoking room declined, its shabby (and smelly) space incompatible with the new, modern domestic ideal. Ivan suggested that a sensory methodology intersected with affective (non-representational) methods but offered greater archival opportunities for sensing past and vague atmospheres.

Matthew Rech engaged a different form of aerial geography in his paper “Politics, Sense and Spectacle: a historical geography of England’s first Airshow”. England’s first airshow – held in Doncaster in October 1909 – happened at a key moment in the development of powered, heavier-than-air flight, and evidenced the emergence of a popular and public aviation culture across Europe. In England, the military had decided, after initial experimentation, that there was no future in aerial warfare (!) meaning that early airfare took place at commercial airfields and, increasingly, in commercial airshows. Drawing on Peter Adey’s work, Matthew suggested that we complement attention to mobile bodies in the air with attention to the stationary bodies on the ground, observing and remembering their early witnessing of mechanical flight. This focus brings our attention to caterers and crowd managers, to semaphorists communicating the programme to the crowd, and to the adaptation of photography from the horse race ground for the promised aerial stunts. Said stunts often failed to materialise to the documented disappointment of the gathered crowds.

Steve Legg’s paper, “Conveying Atmosphere: Weather, Failure, and the Archive of the Round Table Conference” asked three main questions: Is it useful to try to connect meteorological and inter-personal atmospheres? Where is the discussion of race and atmospheres? and What can we know about past atmospheres? Drawing inspiration from Derek McCormack’s 2008 paper, it asked whether we could also study the sensory politics of an international/imperial conference through exploring its relational field of affect (environment), the registering of its atmospheres (sensing bodies) and its temporal representations (anticipation and reflection). What the conference, which brought dozens of Indian leaders to London , showed was that these delegates were presumed to experience the imperial capital’s weather and politics in starkly different (and racialized) ways. Special measures were laid on to keep Indian delegates warm, in a freezingly cold autumn of 1930, while the miserable weather offered ample metaphorical opportunities to the press and politicians to comment on the presumed failures of the conference. Visiting Maharajahs were belittled in orientalising rhetoric (adding “colour” to social events and formal proceedings) while Indian delegates more broadly were accused of intemperate and undisciplined interventions. Reading archives for (rare) reflections on meteorological and inter-personal atmosphere forces productive scramblings of the logic of the colonial archive and (regarding Indian bodies) potential for thinking about the spaces and senses in which racialism made itself felt.

In “Thinking atmospherically: politics and sensory configurations” Shanti Sumartojo presaged work in a forthcoming book, co-authored with Sarah Pink, which explores how we experience atmospheres and how we might go about studying these interactions. Atmospheres were linked explicitly to places (as imaginary, memory, and technological configurations) and analysed through four analytical categories. First, attunement alerts us to how we know the atmosphere we are in, especially where the borders are, and how this knowledge is explicitly political. Second, atmospheres are unpredictable, their inherent diversity making them impossible to marshal. Third, atmospheres are also dependent on, and create, terminology, which itself can be appropriated, slip and re-form. Finally, the methods through which we engage atmospheres dictate how successfully we are able to bring what (to some) is non-representable into the realm of representation through, for instance, working in-depth with participants in national commemoration events (like Anzac Day) to explore their multi-sensory engagements with that time and space.

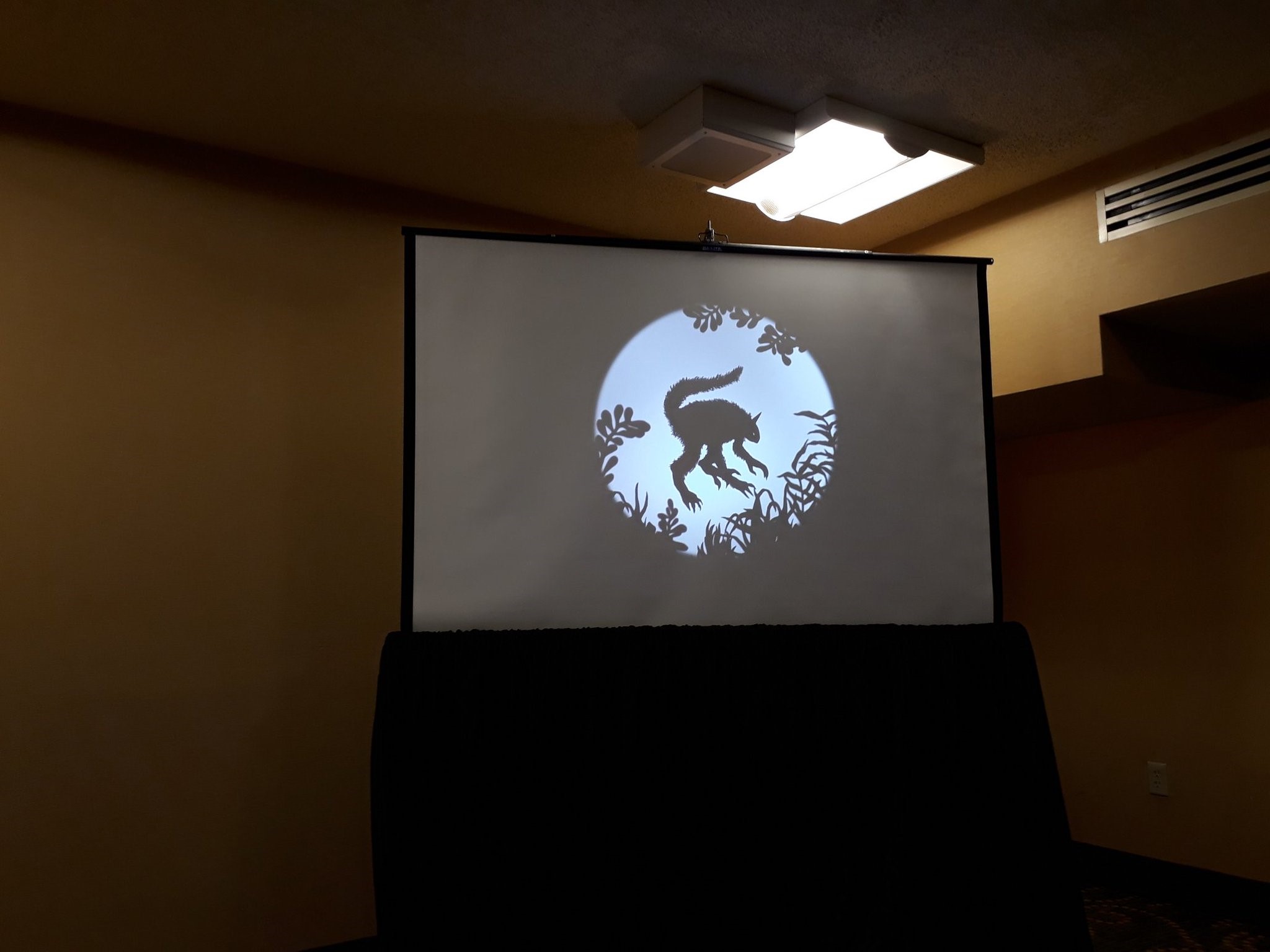

Finally, Tim Edensor presented “Creatively and critically defamiliarizing the world: sensing space otherwise”, which explored the ways in which studies of lighting offer up ways of exploring the cultural and biological partiality of our senses. Lighting presents us with ways of thinking about how space is produced and managed in the modern world, whether through florescent sterility or homely glow. But light and its projection can also be used to defamiliarise space and our experience of it. Examples including art installations that force the human brain to become explicitly aware of the body’s perception of colour, or which use strobe lighting to freeze mobile matter in sensory perception, presented interior opportunities for stimulating the senses. Melbourne’s street light festival marks a different, and public, set of re-enchantments (see the image above), using projections of still and moving images to make people look afresh at their nocturnal environments.

From smoke to air, freezing fog to night-lit streets, the papers offered rich insights into the ways in which politics and geographies are always atmospherically produced and sensed in diverse and provocatively alive ways. This could not have taken place in a better city, in which we listened to some (but not enough) jazz, feasted on creole dishes, and flew home having been battered and drenched by day of incessant thunderstorms and flash floods. Thanks for the atmospheres, New Orleans…

N.b. The featured image is a slide from Tim Edensor’s presentation, depicting Melbourne artist Kyoko Imazu’s work in the Gertrude Street Projection Festival 2017.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply