September 1, 2017, by Jake Hodder

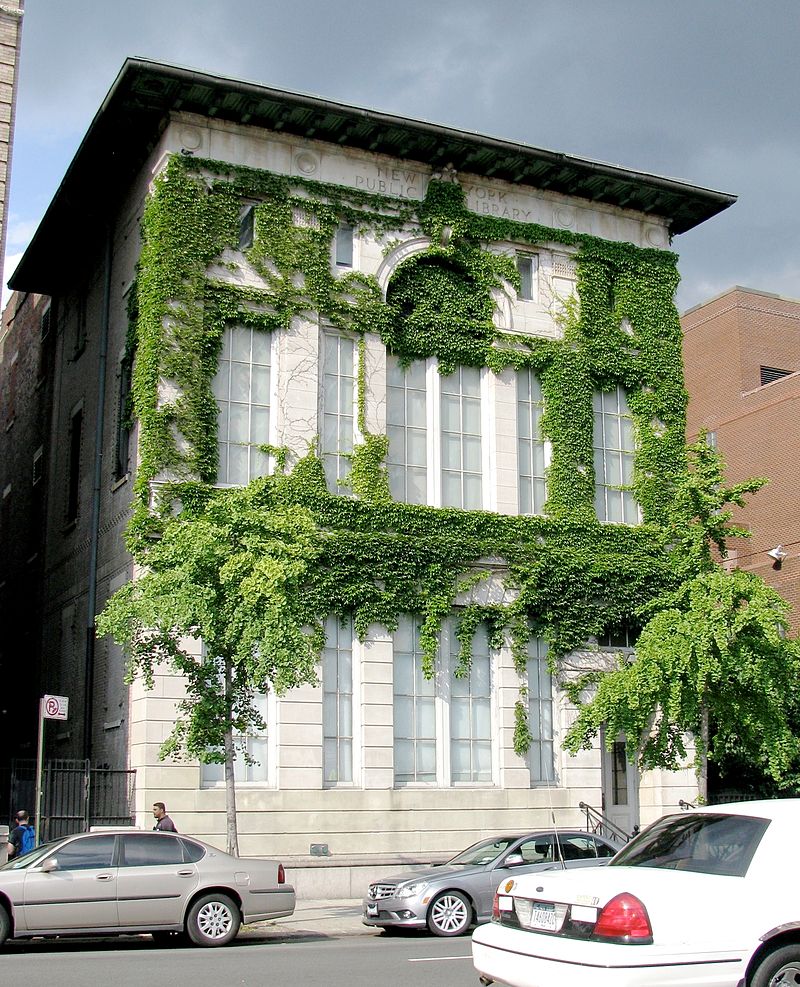

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York City

Located between West 135th and 136th street in Harlem, the Schomburg Centre is part of the New York Public Library (NYPL).

The centre’s history is rooted in the 135th street branch, opened in 1905 as part of the enormous library construction programme funded by Andrew Carnegie. From the start of the 1920s the library became a focal point for the burgeoning cultural and artistic movement of African American artists, poets and musicians known as the Harlem Renaissance. From 1921 it began annual exhibits of African American art and, in 1925, officially began operating as the NYPL’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints. The following year the library convinced the Carnegie foundation to fund the $10,000 acquisition of Arthur Schomburg’s personal collection of rare books by Black authors. Schomburg was a prominent historian who had been outspoken about the political value of excavating black history in the face of ongoing racial discrimination, in particular the role that his collection could play in dispelling the depreciation of Africa and its culture common in white historical work.

In 1932, until his death in 1938, Schomburg became the first curator of his collection at the library, followed by the historian Lawrence D. Reddick, a figure perhaps best known for his close association with Martin Luther King Jr. At Reddick’s behest, the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro History and Literature in 1940, later to become the more inclusively named Schomburg Centre for Research in Black Culture.

The Schomburg Centre is a reference library in which its collections are non-circulating – i.e. they must be consulted on site. Yet despite its rich resources of obscure research materials, the centre’s use continues to reflect its roots as a local branch library. Refreshingly, it’s a space where those using their daily 120mins of allotted computer time to check emails, apply for jobs, or catch up on sports, sit beside tenured academics collecting materials for their next book. In no other library that I have used is the demographic mix of patrons so notably stark. In part this is attributable to the unique shape of the New York public library system (a private, non-governmental, independently managed, nonprofit corporation operating with both private and public financing) which holds a twin commitment to preserve special collections through its research libraries (akin to a university or national archive) and provide broad public access (through local branch libraries). Whilst the Schomburg Centre is one of four NYPL research libraries, it shares a site with the Countee Cullen branch library beside it and sits in the heart of Harlem’s diverse neighborhood. It also, however, reflects Schomburg’s own keen belief that his collection should be accessible in perpetuity to the residents of Harlem at large.

In my own work, which is interested in the ways in which Pan-African ideas were actively and imaginatively constructed in the 1920s and 1930s (not least through the Pan-African Congress which met in Harlem in 1927), the Schomburg Centre has the curious significance of being both a source repository on black history in general, and a research site in its own right. Indeed, the Centre’s formative history in the interwar years played a key role in consolidating black history as a singular body of inquiry, one which drew together African Americans, Africans, West Indians and others. Delegates to the Pan-African Congress visited the Centre, for example, which was then, as now, the outstanding resource on Pan-African history, art and culture. The visit marked the way in which the conference sought to position Pan-Africanism as not only a political and cultural undertaking, but also one which was intensely intellectual and scientific, rooted in the very latest advances in anthropology, history and geography. The development of the Schomburg Centre was a key part of that project, and poses intriguing questions of our own work and what it means to collect a ‘Library of Negroana’?

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply