September 1, 2018, by Jake Hodder

Tuskegee, Alabama

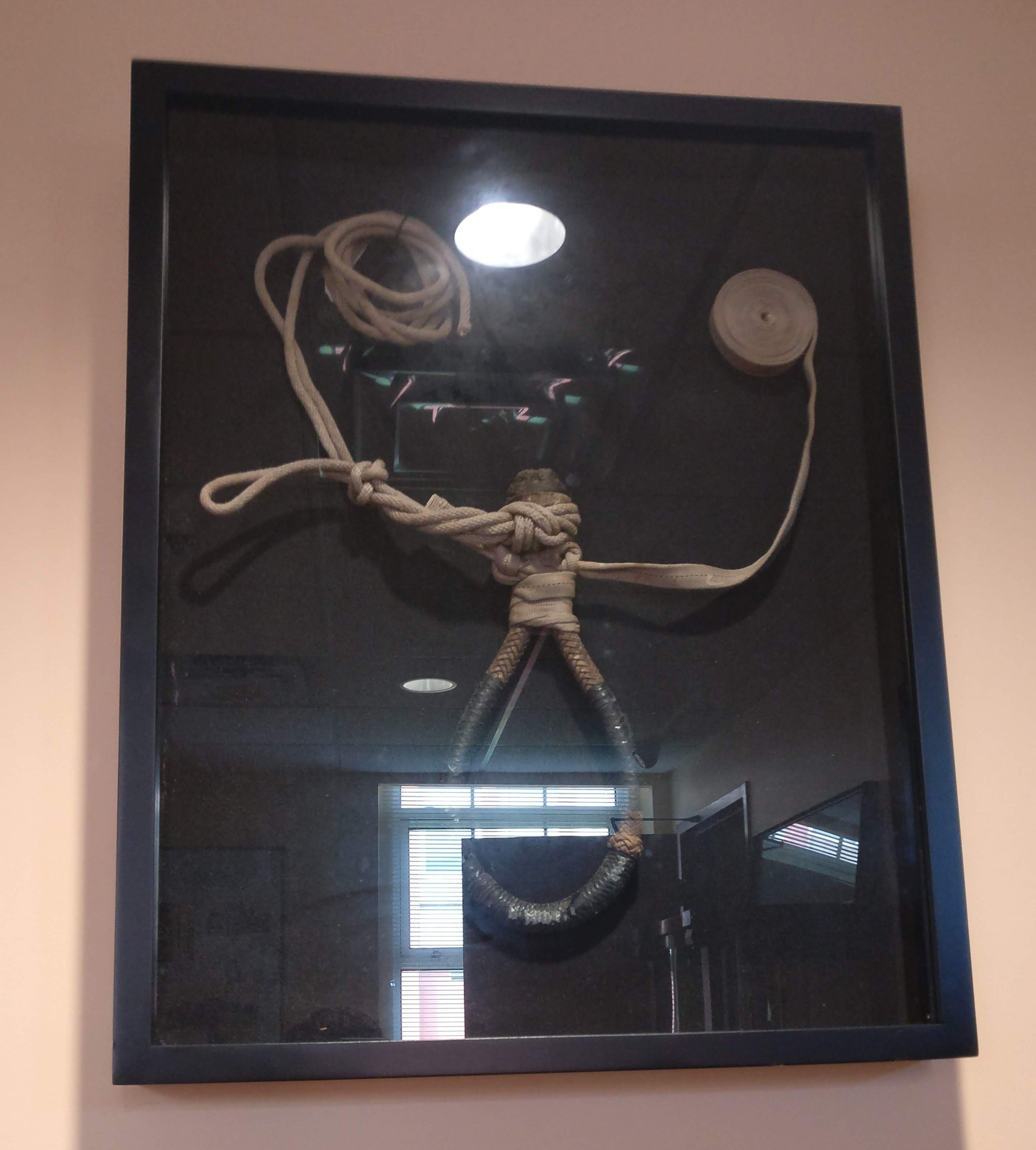

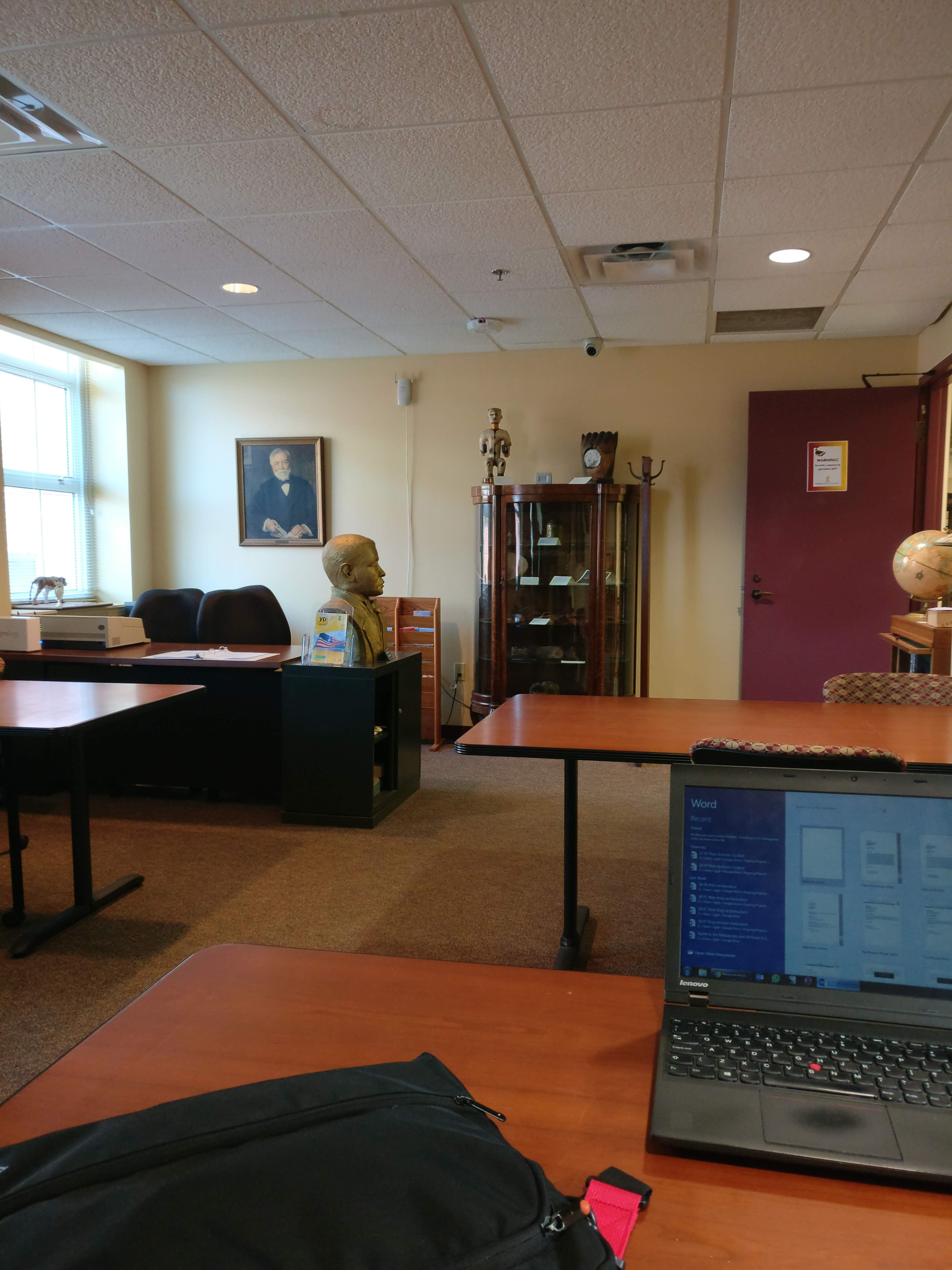

To walk into the archives of Tuskegee University is a reminder of the remarkable role which the institution has played in shaping the African American experience. As soon as you enter, the juxtaposition of that experience is visibly apparent; a story of both the spectacular vibrancy of black popular culture, but also the horrors it developed in spite of. The entrance exhibits the flamboyant jacket worn by Tuskegee’s Lionel Richie and the Commodores, but beside the reading room desk hangs a rawhide whip and cotton rope donated by a 12 year old boy whose relative was lynched with it; specks of blood still visible. Along with the equally haunting national lynching memorial (officially known as the Memorial for Peace and Justice) just down the road in Montgomery, it is a troubling reminder that there are few places where history is so raw, and so emotionally fraught, as in Alabama.

The small city of Tuskegee, situated midway on the I-85 between the state capital of Montgomery and the historic college town of Auburn to the East, has played a central role in shaping that history. Tuskegee University is a private, historically-black college established in 1881. It is most commonly associated with its first principal Booker T Washington, ‘the wizard of Tuskegee’. As the most powerful African American at the time of his death in 1915, Washington profoundly shaped every aspect of the institution’s work and approach. He focussed on practical concerns of black uplift and industrial training, rather than more divisive political questions of civil rights or voting reform. Whilst figures like W E B Du Bois criticised Washington’s accommodationist position, the network of wealthy American donors it allowed him to garner (including Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, George Eastman) enabled Tuskegee to become a leading centre of black education, led by an impressive and accomplished faculty.

My interest in Tuskegee was two-fold. First, I was interested in Robert R Moton, the college’s second president who served from 1915-1935. In 1918, Moton was invited to travel to France by President Woodrow Wilson to inspect U.S. black troops stationed overseas. Travelling onboard the USS Orizaba, Moton shared a compartment with Du Bois who was also travelling to France to organise the First Pan-African Congress in Paris, which convened in February 1919. Moton’s detailed letters and reports of post-war Europe offer a unique window into African American wartime experiences and the broader context in which the delegates met. But Moton, unlike Du Bois, was also embedded within official US government networks abroad and privy to confidential and sensitive information. A number of letters reveal conclusively something long suspected but unproven, that Du Bois was under government surveillance in Europe, driven by a fear that the Congress would impinge on US foreign policy objectives at the Peace Conference and beyond.

Secondly, I was there to consult the archives of Tuskegee’s Department of Records and Research. Tuskegee’s association with practical training belies the fact that it became an important intellectual centre and clearing house for collecting and organising black history. Holding major international conferences, annually producing the Negro Yearbook and, in 1928, publishing the exhaustive Bibliography of the Negro in Africa and America, were just some of the ways in which the institute came to shape the political, historical and geographical contours of race in America. Papers of figures like Monroe Work and Jesse Guzman reveal the labour, scholarship, and fund-raising required behind-the-scenes to enable this to happen. This work was underpinned by a shared belief that when presented with the scale and nature of its race problem in a scientific and systematic way, the nation would instinctively bend toward justice. It is a logic which has shaped Tuskegee’s unique contribution to the African American freedom struggle – a conviciton that scholarship, education and training are inextricably political acts which quietly, but profoundly, can reshape America.

Reading these papers whilst seated beside a hanging noose is to be reminded of the extraordinary assumption of such a position: that the terror of white supremacy would naturally yield to logic and reason.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply