March 1, 2017, by Stephen Legg

The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi

Undertaking historical research in India presents the researcher with a more broadly familiar set of dilemmas: oral or archival history; popular or elite; published materials, commercial products, popular objects and social movements, or official documents, state repositories and the archive of power? These are, of course, false distinctions; the popular press tells us much about broader government while official archives contain rich collections of popular memory. New Delhi stands out for having an institution which embodies the crossing of this distinction, in the shape of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML). It functions as a repository of official nationalist history in the form of a vast library, personal papers, newspapers and journals containing material about, but also supplementary to the study of, modern India’s colonial, anti-colonial, and post-colonial history.

The NMML is commonly referred to as Teen (three) Murti Bhavan (building). A murti is an object of worship and I had been told on a few occasions that murtis in question were three of the beautiful trees that stand in the grounds (See image above). The complex, however, takes its name (as does the road, Teen Murti Marg) from the monument at the centre of the roundabout outside of its gates (see image below). This First World War memorial features three statues (murtis) commemorating the Indian war dead from the three Princely States of Jodhpur, Hyderabad and Mysore, designed by Leonard Jennings, who had served in France during the First World War and went on to produce numerous statues in India between the wars.

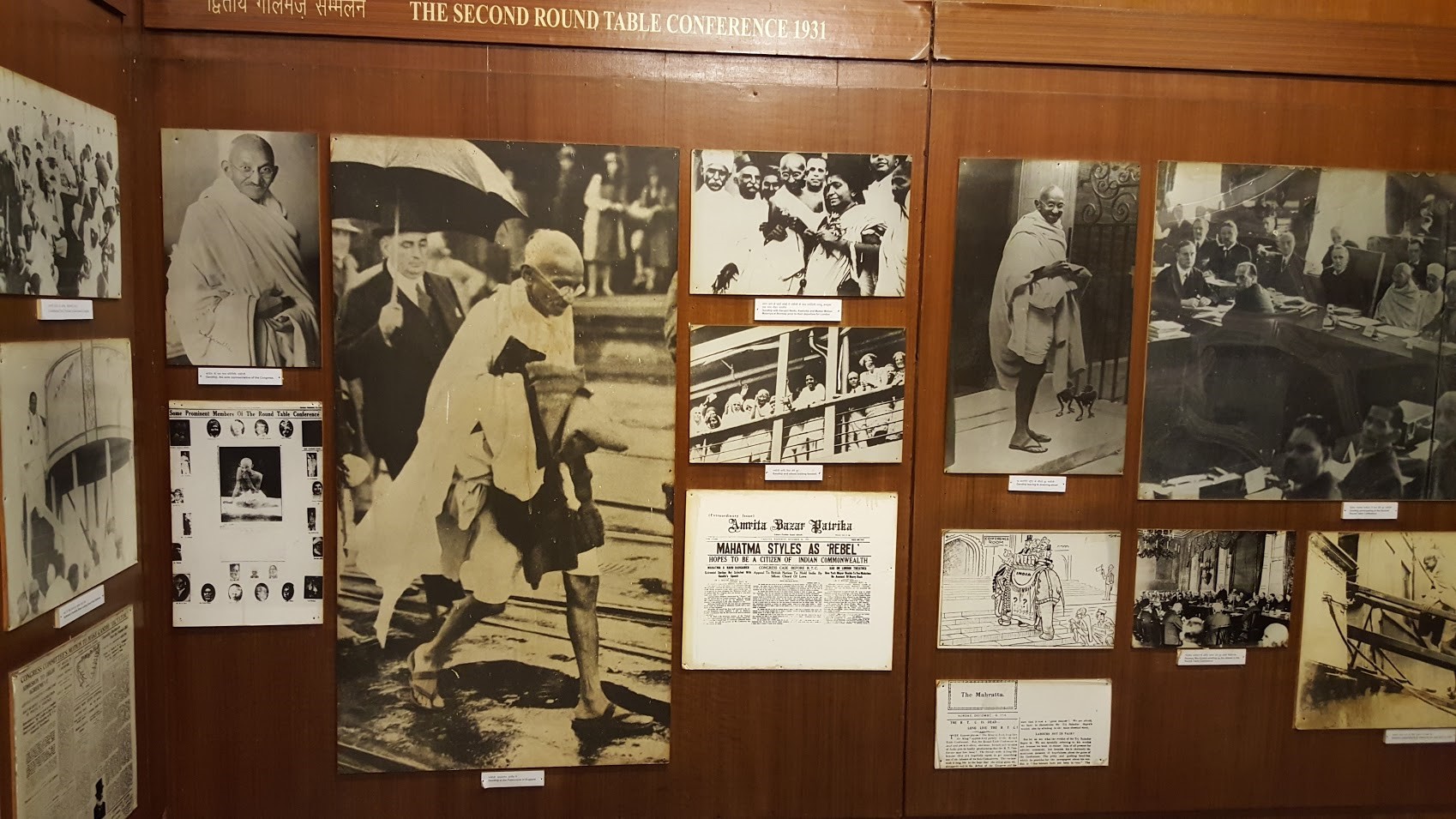

The “Imperial Service Cavalry Brigade memorial” acts as a reminder in the heart of the capital of the fracturing of the Indian Empire between British and Princely States (the coming together of these states into a federation was one of the key outcomes of the Round Table Conferences). If the subject of the monument fractures the sense of unity in the capital, its design and geometry fits perfectly. Edwin Lutyen designed the outline of the capital on a series of geometric principles. From the Viceroy’s House (Rashtrapati Bhawan) Kingsway ran due East to the ancient ruined Hindu capital of Indraprastha, while 60 degrees to the north-east in Old Delhi lay the Jama Masjid, the largest mosque in India. From this angle and the perpendicular avenue of Queensway (Janpath) the city was structured around a series of hexagons and right angle triangles. When they intersected they formed roundabouts at the junction of equilateral triangles of imperial privilege. Teen Murti Bhawan is situated upon one of them, with each of the three roads overseen by one of three memorials to the Princely War dead. One gazes towards the Gymkhana club, one down the anomalously curved Willingdon Crescent (now Mother Teresa Crescent, curving around the Viceregal [now Presidential] Gardens), leaving the third to stare down the Viceregal and now Presidential lodgings, in perpetuity.

The memorial was so placed because Teen Murti Bhavan was designed as the official residence of the Commander-in-Chief, the head of the military in colonial India. The location was perhaps the most prestigious in the capital’s carefully orchestrated residential landscape; to the south of Kingsway were the most prestigious “bungalows”, the largest of which were more like mansions with vast compounds and servants’ quarters. It was designed by Robert Tor Russel the architect of the neo-classical crescents of Connaught Place. These buildings lacked Lutyens’ genius for welding the (highly selective and essentialised) architectural styles of the East and West. But they didn’t have the politically symbolic weight of the central administrative buildings. For commerce and military a completely western style was deemed appropriate, even if they effaced the Indian products on sale and the Indian men on guard.

After Independence the Viceroy’s House became the President’s official lodgings, continuing to represent the highest symbolic sovereign in the land. In a perhaps not unintentional move, Nehru made the home of the military during the colonial autocracy the home of the elected Prime Minister during the postcolonial democracy. He and his family lived there until his death in 1964 after which the house became a memorial to the Nehru dynasty and the library (and a planetarium) were built in the grounds. The architecture couldn’t be more different; colonial modern gave way to tropical modern and Nehru’s development aesthetic (see image above). The library is not for the public, it is a research institute requiring membership and official documentation to gain entry. Its collections include those of the Congress party and many of the nationalist elite, while an oral history project recorded the experiences of many leading nationalists and social reformers, including many of the participants at the Round Table Conferences.

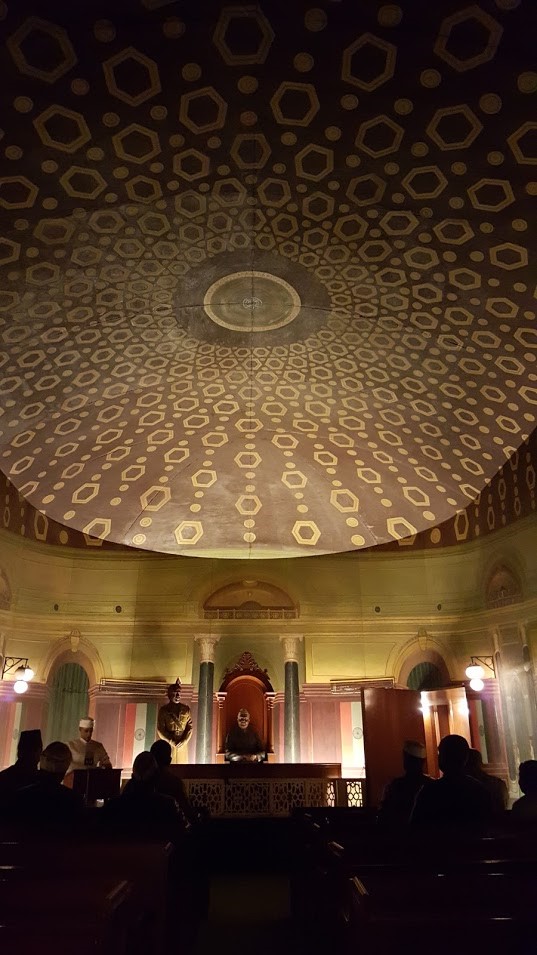

The location is stunning and researchers can take their lunch in the grounds, accompanied by ever more monkeys and a resilient muster of peacocks. The Museum has been renovated and is fascinating not just for its collection but for its setting, by far the largest freely accessible colonial building in New Delhi (the second best being the bungalow in which Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, was assassinated a short walk away). The vast two story building has been converted into a walk through exhibition, starting with the Nehru dynasty history, which charts Jawaharlal’s transformation from imperial elite (Harrow, Trinity College Cambridge, Inner Temple) to socialist man of the people. Upstairs the display continues, taking in the old ball room and balcony (see images above), explaining the nationalist movement more broadly, including panels on the Round Table Conferences (image below). Interspersed amidst this long secular trajectory are sacred sites of pilgrimage. Rooms occupied by the family have been preserved, replete with sofas sat upon, beds slept within, and desks worked away at, into the early hours (image below): Indira Nehru’s, as she was, bedroom; Jawaharlal Nehru’s study, and the bed in which he died. The Memorial concludes with a coup de theatre (image below); a miniature mock-up of the Legislative Assembly Chamber in which Nehru’s famous “tryst with destiny” speech was delivered and the constitution was approved, through which you have to pass to exit the building, bringing every visitor (especially the massed ranks of school children) into the moment when imperial autocracy was cast off and universal franchise was brought in. The chamber is darkly lit and one has to tread slowly and carefully, which may or may not be the Museum’s final lesson.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply