June 17, 2024, by lzzre

Northern Light in Darkened Times: Attending Arctic Congress 2024

A blog post by Dr Peter Martin, Assistant Professor in Cultural and Historical Geography.

As recent research in the School of Geography has shown, conferences are always affected by the environment and atmospheres that surround them. A notably unique affective atmosphere greeted me as I arrived into the city of Bodø in Northern Norway to attend Arctic Congress 2024 – a joint conference between UArctic, High North Dialogue and the International Arctic Social Scientists Association (IASSA).

Situated 50 miles above the Arctic Circle, Bodø receives nearly 24 hours of daylight at this time of year – a geographical phenomenon that delegates fully embraced at the conference’s opening drinks reception. Catching up with old friends and colleagues and being introduced to new ones while the sun poured continuously through the enormous windows of the Ramsalt Hotel, it was only by checking our watches/phones that we realised that 10pm, 11pm and indeed 12am had already passed us by. Returning to my hotel overlooking the beautiful Bodø harbour, I closed the (thankfully black-out) curtains and tried to get some sleep before the conference proper began.

With light comes darkness however, and there were constant reminders over the subsequent days of the conference that a troubling shadow was looming large over proceedings. The current geopolitical situation following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has of course had profound implications for geopolitics around the world, but this has been felt particularly acutely in the Arctic. This difficult geopolitical reality was unavoidable at the conference, and almost everyone in attendance had either been impacted directly by the troubling situation in Ukraine, or knew someone that had. The absence of many Russian colleagues who had been denied entry to Norway to attend the conference was keenly felt. Various panels and sessions had been arranged to discuss the issue and reflect on what the future of Arctic social science research might look like without access to Russian territories, colleagues and research participants. Indeed the conference even made headlines in the local Norwegian news, as concerns were raised that Russian spies were possibly lurking amongst the delegates. There was a palpable sense across the conference that a promising (and yet always precarious) thirty-year period of truly circumpolar Arctic research, collaboration and engagement had now come to an end, and that this had been replaced by an anxious uncertainty regarding what the coming months, years and decades might bring.

Other political issues were also at the forefront of the conference. Bodø is situated in Sapmi, the lands of the indigenous Sami community that span across Northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Many members of the Sami community were in attendance at the conference, and leaders from the Sami Council and Sami Parliament gave articulate and impassioned speeches at the plenaries describing the challenges their community faces both in relation to climate change, but also in terms of political recognition and involvement in confronting it. Members of other indigenous groups from across the Arctic and sub-Arctic including Inuit, Nenets and Métis representatives were also present. Many of the panel sessions were devoted to the promotion of indigenous knowledges for both understanding and tackling various environmental issues, including sea ice retreat, permafrost thaw and depleting biodiversity. Studying the Arctic as I do from the UK can at times make these vital and complex issues feel very far away. But chatting with these people and hearing stories of the intense and complex challenges they face in their day-to-day lives – but also their resolve in tackling these challenges – was a humbling yet inspiring experience.

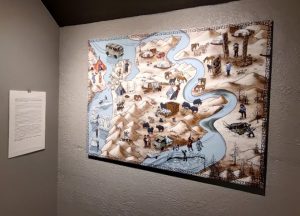

Although primarily an event focussed on social science, the organisers had also ensured that the arts and humanities were also given a prominent footing. A cultural programme including concerts, exhibitions and film screenings accompanied the academic discussions, and it felt like every corner of Bodø had been requisitioned for these purposes. Importantly, indigenous contributions were again at the forefront. At the opening ceremony, delegates were treated to a beautiful joik (traditional Sami song), while burgers and wraps containing meat from the reindeer herded by Sami were also on offer throughout the conference. Indigenous artwork was also on display in galleries across the city, with intricate Iñupiat beadwork positioned alongside a mural produced by the Nenet community showcasing the contemporary Arctic and its challenges. Despite common assertions that the region is somehow ‘empty’, these various activities and displays certainly showed that the Arctic is of course alive with culture and creativity.

With no nighttime to differentiate one day from the next, my time in Bodø went by all too quickly. Before I knew it, it was time for the closing ceremony and conference gala dinner. This was hosted in a tent inspired by the traditional Sami lavvu and food cooked on an enormous barbecue was shared amongst the newly-formed conference community. A personal highlight of the entire conference was getting to watch a performance of katajjaq (traditional Inuit throat-singing) by two Inuit performers. The whole tent was completely mesmerized, and chatting to one of the performers afterwards she joked that it was the only moment during the whole conference where nobody said a word!

The contrast between the difficult topics discussed at the sessions and the uplifting interactions between the international delegates over the five days of the conference was certainly the element I will remember most about Arctic Congress 2024. As we find ourselves in a new phase of Arctic geopolitics and research – one that sadly seems to be shrouded in darkness and disunity – it is important to remember that those of us researching the region remain committed to working together where possible to shed crucial light on the complex challenges it faces.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply