September 27, 2022, by lzzeb

The Geography of Geography

A blog by Steve Legg

As we recover from the pandemic we are rediscovering many of the ways we used to work, and finding them much changed. Conferences are part of the life cycle for geographers; part of our academic annual rhythms. During the 2020 lockdown they were mostly suspended. In 2021 some took place face-to-face, others in virtual space, others in a hybrid between the two. Online sessions robbed us of many of the pleasures of conference life: the chance encounter, the coffee-room chat; the body language and jazz-hands of a caffeine-fuelled presenter. In 2022 the annual conference of the Royal Geographical Conference with the Institute of British Geographers took place in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in both a recognisable and new form. While there were covid-precautionary requests, there was no mandatory social distancing. Sessions could take place solely face-t0-face, in a hybrid of in-person and online presentations and attendance, or solely online (presenting logistical challenges for those at the conference). The technological challenges of hybrid sessions were fantastically negotiated by a small army of student supporters who staffed the zoom calls, monitored the chat rooms, and saved us the embarrassment of screwing up the IT, despite our best efforts. Whilst still expensive, online sessions allowed delegates from around the world to save on the costs and carbon of national and international travel. So, what is the case for continued in-person conferencing?

During lockdown myself, Mike Heffernan, Jake Hodder and Ben Thorpe worked on the edited collection Placing Internationalism: International Conferencing and the Birth of the Modern World, and since then I have completed Round Table Conference Geographies: Constituting Colonial India in Interwar London. Both volumes explore the spaces of conferencing and their effects. Many of the benefits of conferencing can be considered in the abstract and recalled in general; the dinner, the chats, the academic contretemps, the booze. Central, of course, is the organisational labour of the academic conference.

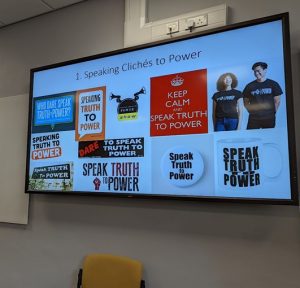

Every three years the RGS-IBG conference ups sticks from its lodge in South Kensington and perambulates around the United Kingdom. The royal tour was hosted this year in lavish fashion by the University of Newcastle, in its stunning campus north of the city centre. The RGS and Newcastle University staff seamlessly facilitated the usual mix of plenary lectures, discussion panels and standard sessions. I was lucky enough to be invited to chair a session on the “Historical Geographies of Sensation: 1800 to the present” (featuring Nottingham’s Rachel Dissington on the auditory geographies of fog horns, bells, sirens and recordings). I also co-convened a session considering Foucault’s last lectures on the ancient concept of parrhesia, the courageous act of risky truth-telling. This is often thought of as “speaking truth to power”, an interpretation caustically taken down by Professor Philip Howell.

The academic work of the conference changed form in Newcastle compared to London, but did it change its content and nature? What is harder to recall or put into words, compared to locational and administrative difference, is the sheer affective force of place; the geography (location) of Geography (discipline). Travelling to a new city has its charms and pleasures, for journey-thirsty geographers for sure. But what the conference reminded us, after four or so years, was of the deep and profound stimulation of place. The last ten years has seen the surge in popularity of writing retreats, in which academics pay often-large sums of money to go an often-rural retreat to be well housed, healthily fed, and disciplined into monastically silent hours of writing. Sceptical of their point (presumably a sop to procrastinators), I was a late convert. The point, it seems, is not the carceral discipline of the retreat, but the stimulating effect of a different, safe, well-furnished place.

Conferences serve the same function, taken for granted until the enforced non-movement of the Covid years. For me this applies to the train journey too, times in which I always work well, because not in spite of the distractions. But the brain clearly works differently when it sets to work in different locations. This included the workspace of the University of Newcastle’s campus, both its stunning architecture and its wild-flowered gardens. But it also included the conference city, not least at the party hosted across the River Tyne under the world famous bridge. Who couldn’t be inspired, or at least prodded into new thought?

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply