May 6, 2021, by lzzeb

The Map Blog. Locating the Nottingham General Asylum

In this special blog, David Beckingham uses maps from the School of Geography and University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections to trace the site of Nottingham’s General Lunatic Asylum in Sneinton, now King Edward Park. It is a version of a talk David gave at an event earlier in the year to mark the completion of BACKLIT Gallery’s Heritage Lottery funded Nottingham Asylum Project [1].

Nottingham was an asylum pioneer. The town’s General Hospital, which opened in the eighteenth century, was not set up to treat people that what were understood to be suffering from unsound mind. But in an innovative partnership, at the beginning of the nineteenth century the justices of the peace of the county and town collaborated with a group of voluntary (private) subscribers to provide a dedicated facility, which officially opened beyond the town boundary at Sneinton in 1811.

The Nottingham project reflected broader changes in understandings of mental illness, which posed that patients could be treated with a more therapeutic care regime. The geography of the asylum mattered, separating patients from their existing urban environments and networks of connections [2].

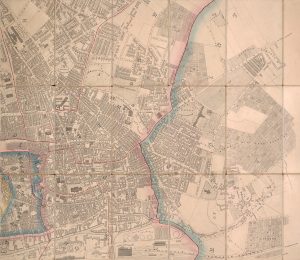

Figure 1, a map by Edward Salmon published in the 1860s, shows just how close the Nottingham site was to the expanding city (the asylum is on the middle row of map panels, to the right (east) of the pink and blue boundary lines). The map shows some of the other institutional responses to Nottingham’s urban problems, including the workhouse (upper left panel), and House of Correction (second row). Such institutions were not simply spaces to sequester problems behind high walls; like the asylum, their designs often reflected complex ideas about moral discipline and reform.

Figure 1: Detail of east Nottingham, Edward Salmon, Plan of the town of Nottingham and its environs (London: Wyld) [186-?] University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections (East Midlands Special Collections Not 3.B8.E6). Not for reproduction. Click to enlarge the image, or to view a higher-resolution version of the map, please follow the link to the University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections Digital Gallery.

The voluntary subscribers abandoned the asylum partnership in the 1850s, as overcrowding was understood to be compromising treatment. They moved their patients to a larger site called Coppice Hill in north Nottingham. This did not resolve the local pressures on the asylum site, however, and nearby baths and washhouses hint at the kinds of environmental problems that might have stood at odds with any therapeutic ambitions. In time the city also left the partnership, constructing its own facility at Mapperley. Finally, in 1902, with Sneinton now part of the city, the county patients were removed to a new facility on a much larger site at Saxondale near Bingham.

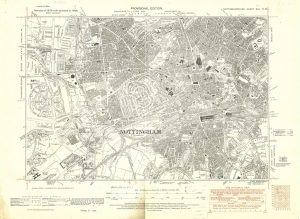

Figure 2: Nottingham, Ordnance Survey Provisional Edition, XLII NW 1938, 6 inches to 1 mile University of Nottingham School of Geography Map Collection. Click to enlarge image.

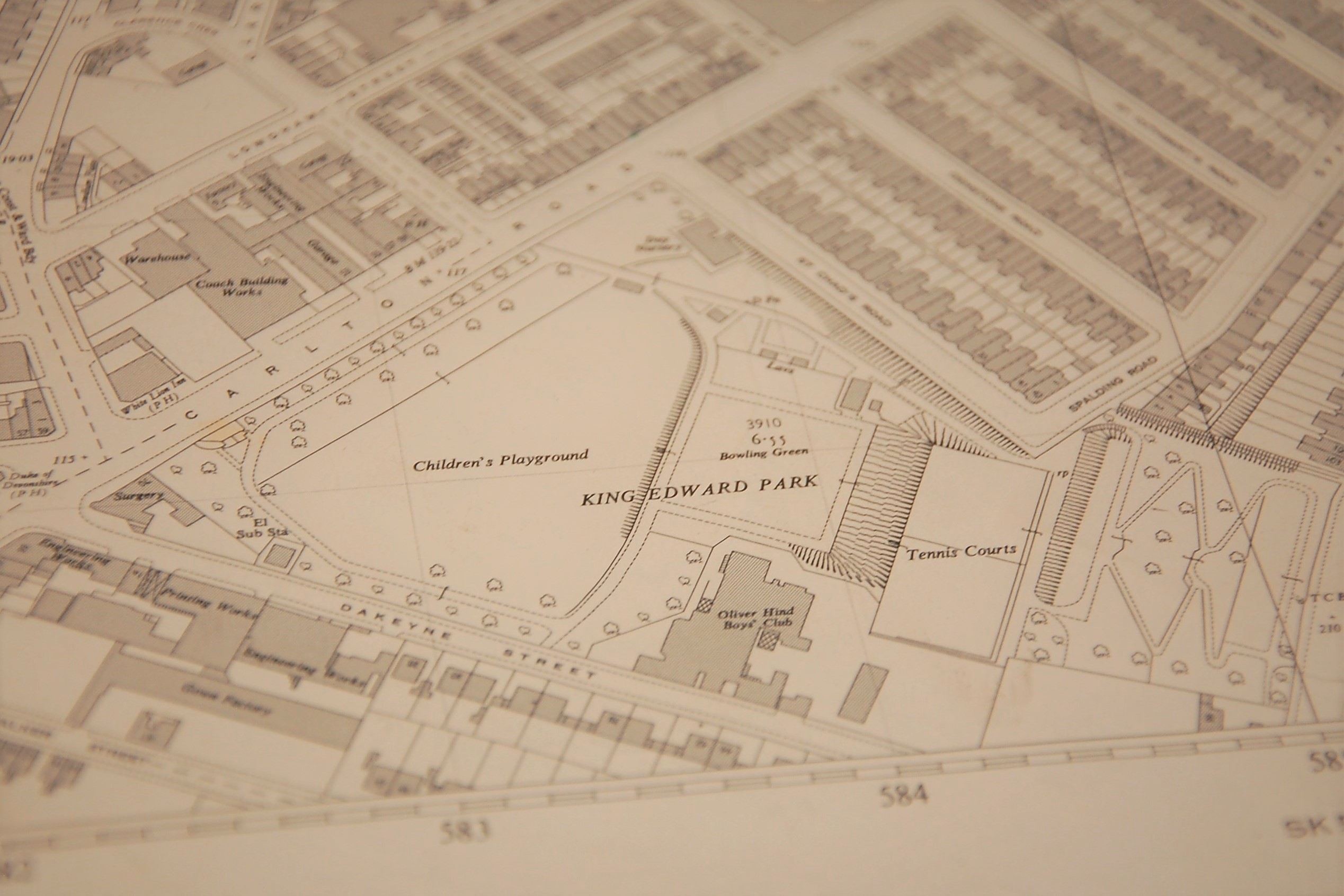

The expanding city ultimately surrounded and overwhelmed the asylum site. Figure 2, a map from 1938 on an earlier base, hints at the changes that were remaking twentieth-century Nottingham, with space for new housing out to the west, and the University College in the bottom left of the map. To the east of the city centre, the asylum is now King Edward Park, a rare empty space between tight rows of streets. This can be seen even more clearly on my final map, Figure 3, a 1955 Ordnance Survey plan whose details allow us to locate the asylum site amongst Nottingham’s textile works and other places of industry.

Figure 3 (and title image): Detail of King Edward Park, Ordnance Survey Plan SK 5840, 1955, 1:1,250 University of Nottingham, School of Geography Map Collection. Click to enlarge image.

If the asylum was a spatial response to urban life, designed to separate people from problem environments, then these maps show how the site and the changing urban nature of Nottingham shaped what could be done there. In short, the asylum was not a space isolated from industrialism. It is noteworthy that these maps show a series of boundaries: city and county; parishes; public and private spaces; diseased and healthy; freedom and control. Maps, just like the asylum, were an attempt to order, reorder even.

Discover more about map and archive collections at the University:

University of Nottingham School of Geography Map Collection, University Park Campus: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/geography/about/map-services/map-collection/index.aspx. For more information, please contact Cartographic Unit Manager Elaine Watts.

University of Nottingham Manuscripts and Special Collections, Kings Meadow Campus: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/. In addition to many maps of Nottingham, the archive holds printed materials relating to the foundation of the asylum.

References

[1] For more information about the BACKLIT Nottingham Asylum Project, see: https://nottsasylumproject.ucraft.site/

[2] My reading of the asylum site is informed by the foundational work of geographers Professor Hester Parr and Professor Chris Philo. See: Hester Parr and Chris Philo (1996) ‘A Forbidding Fortress of Locks, Bars and Padded Cells’: The locational history of mental health care in Nottingham (Historical Geography Research Series, No. 32).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply