October 24, 2018, by Lexi Earl

A brief history of Africville, Nova Scotia

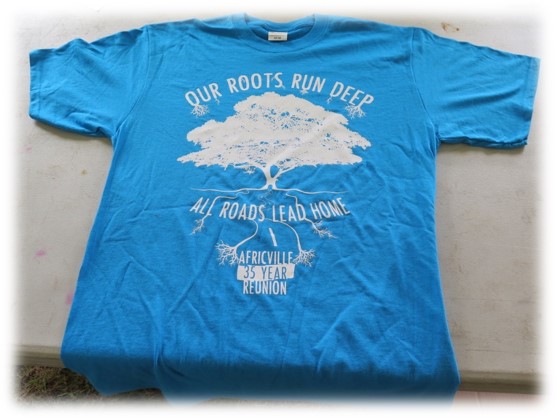

In this blog post we discuss the origins of Africville, a community in Halifax, Canada. Exploring the history of Africville was part of the Geographies of Black Protest research project conducted by Dr Karen Salt, Bright Ideas Nottingham (a social enterprise based in Nottingham) and colleagues, funded by AHRC as part of the network funding for the UN Decade for People of African Descent. In July 2018, the Future Food Beacon supported a return trip to Africville for Dr Salt and her colleagues, so that they could participate in the 35th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Africville Genealogy Society. Africville has a fascinating food history, which Dr Salt is currently investigating.

This post forms part of our series on Food Stories, and our interest in lives lived ‘on and in the margins’.

Africville was an African-Canadian village located north of Halifax in Canada. It was founded in the mid-18th century. Inhabitants of the village were Black Nova Scotians from a variety of origins including: runaway slaves, freed slaves, Black Loyalists promised land and/or their freedom by the British military for fighting against the US, and Jamaican Maroons. During the 19th century Africville grew and expanded with these waves of inhabitants and by 1917 had a peak population of roughly 400 families.

The rural community was self-sustaining, culturally rich, and had strong community ties. Alongside houses, the community had its own school, ice hockey team (the Africville Brown Bombers), the Seaview African United Baptist Church (est.1849), and many residents ran fishing businesses from the Bedford Basin. But as a community, Africville residents experienced constant economic exploitation by the City of Halifax, alongside governmental neglect of the environment which resulted in the systematic oppression of the Black community. For many, Africville represents the often ignored oppression faced by Black Canadians. Throughout Nova Scotia, Black settlements thrived, resisted and survived in challenging and hostile conditions. Although Africville provided the main impetus for the Geographies of Black Protest team, they recognise that it is only one of many stories that challenge the national myth suggesting that Canada is not a country founded on white supremacy, racism, and colonialism. During this visit, the research team were able to explore further links with communities in North Preston and East Preston.

Africville was a self-sustaining community. Local fisherman sold their catch locally and in Halifax. Other businesses included agricultural trade and small stores that opened towards the end of the 19th century. Africville became an escape from the anti-Black racism that permeated throughout Halifax and also provided opportunity for employment that were not widely available for Black citizens elsewhere.

Africville was not well served by the local government. Residents were required to pay taxes to the city, but basic services like running water, sewers, and paved roads were not provided. Municipal services like public transport, police protection, recreational facilities, and rubbish collections did not exist. The city then compounded this lack of services by building industrial developments around Africville like the fertiliser plant, slaughterhouses, a prison, and the Infectious Diseases Hospital, essentially surrounding Africville and its residents with potentially toxic contamination and a hostile environment. Africville became classed as a slum, and following the 1917 Halifax Explosion the city was able to move to redevelop the area specifically for industry and eventually evict the residents. Despite protests and continued challenges by the inhabitants to the municipality, by the 1960s, Africville residents were forcibly moved to other areas in and around the city of Halifax.

Despite these seemingly insurmountable obstacles, daily life in Africville was rich, and full. Often, communities like Africville are written about in terms of want and lack, as in lacking in… or wanting for… But the reality of daily life is rarely that simple. On her research visit, Dr Salt was able to examine Africville artefacts within the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. One artefact that caused her pause was a large stove. She explained that the ornate stove represented more than merely a place to cook. It was a commanding and artistic testament to the centrality of food. Thinking about this sparked many questions: What did Africville residents grow? What did they eat? How did their migrations shape the food traditions they created? Discussions with Africville Museum volunteers and staff, and the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia suggest that food was a central feature of life in the community. Dr Salt and her team are now pursuing these tales and processes of food as a way to discover the past and share food traditions and agricultural practices with future generations.

For more information on Africville, see:

https://www.saveur.com/roots-of-african-nova-scotian-cuisine#page-11

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply