July 5, 2021, by Lexi Earl

The great duckweed hunt! Part one in a botanical tale of exploring natural variation around us

This post is written by Kellie Smith.

Welcome to our new series, showcasing duckweed! We have written about duckweed before, but these posts showcase PhD candidate Kellie Smith’s fieldwork hunting duckweed around the UK.

Kellie is an avid duckweed collector and researcher in Food and Agriculture at the University of Nottingham. She is passionate about duckweed ecology, physiology and developing duckweeds as a food and feed source. She is supervised by Levi Yant, Tony Bishopp and Erik Murchie, and is funded by the Future Food Beacon. More about Kellie’s work on duckweeds can be found on her website.

Kellie Smith, right, with duckweed samples

Why hunt duckweeds?

After a year of COVID-19 delays, my great duckweed hunt has begun. Why am I hunting duckweeds anyway?

Duckweeds are floating plants which are an important part of a water ecosystem, providing shelter for frogs and newts, and food for fish and ducks. Despite their ecological importance and potential applications, they are widely perceived as a weed, spreading rapidly to produce a green carpet over water surfaces. In the summer this can result in large populations of duckweeds blocking waterways, making them a nuisance for humans and proving challenging to remove. Despite their bad reputation, duckweeds perform the important role of removing excess nutrients present in watercourses and are often associated with water courses with leached nutrients from agricultural run-off.

Little is known about the species makeup and environmental variation in duckweed habitats in the UK. Native UK species, including the common duckweed Lemna minor, are broadly found throughout the UK. The lesser duckweed, Lemna minuta, has invasive status and was introduced in the south of England from Europe via ports. It is currently invading northern climes. These species together provide a model to study traits involved in rapid spread and growth of the foreign duckweed relative to its native cousin.

I am using botanical collections to identify duckweeds with potential food applications and to understand their successful evolutionary and adaptive strategies. We are growing our isolates in common environments to compare traits such as growth rates and ion accumulation, and genome sequencing hundreds of them to scan for genes associated with various adaptive traits. We are also doing UK wide surveys to understand duckweed population dynamics and to identify and track invasive species.

Southern coastal ports of the UK have been identified as entry zones of duckweed species from Europe so we have included the south east and south west areas of England in our hunt.

Udimore village pond in Rye, near Hastings is high in plant diversity. The pond is covered in water starwort, two species of duckweeds, ‘common’ and ‘lesser’ duckweeds, algae and reeds, which to the eye appear as an extension of the grassy daffodil field.

Duckweed hunting in the South East

The first stop on my summer of duckweed hunting: the South East! Here we ask the question: are duckweeds tolerant to iron-rich water?

Wells and streams high in iron flow through the large central park of Hastings where three large lakes sit a mere one and a half metres from the sea. It was a mildly sunny day when we checked these sites and all of these yielded no duckweeds, much to our dismay, and hope was almost lost after checking waters and their associated twigs, flowers and other debris aggregates for the tiny, floating plants.

Then, hooray! A sprinkle of duckweeds lined an iron-rich part further upstream. All was not lost, and this marked the first find of the season! The initial concern about finding duckweeds at all was luckily short-lived as we went on to find duckweeds everywhere. Even in early spring the duckweeds had certainly been busy as more streams, ditches, ponds, moats and rivers checked were all packed full of them!

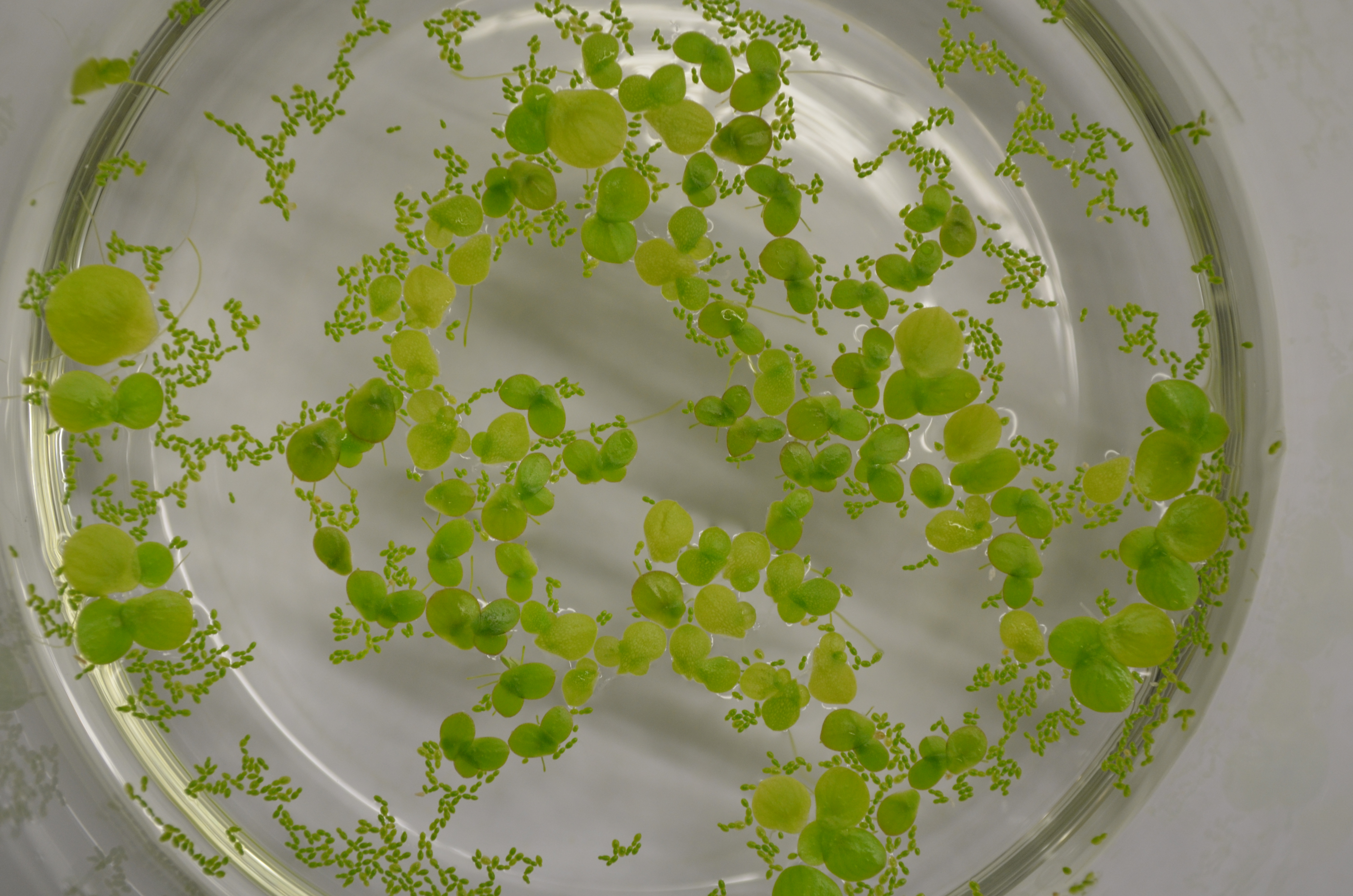

Pictured above: three duckweed species – ‘common duckweed’ butterfly-shaped Lemna minor, ‘ivy-leaved duckweed’ Lemna trisulca and small invasive Lemna minuta were found in Hastings. Many thanks to Aneesh Lale for taking the photographs of these species.

Duckweed hunting across the south east: The red crosses mark the duckweed ‘treasure’ discovered in and around Hastings coastline.

Then we really did strike gold in a grassland bog, six metres inland in a place called Westfield, as we found our first ivy-leaved species, Lemna trisulca; a representative to add to the UK botanical collection. This species grows under water rather than floating at the surface and is more difficult to spot compared to other species. Duckweeds are collected into sealed falcon tubes containing tap water, labelled with the site number and picked using an appropriate reaching device, such as a long twig. Falcon tubes containing our species are stored such that they receive natural daylight and temperature conditions until returned to the lab. The new Lemna trisulca isolate will be grown in controlled climatic chambers alongside other UK species to compare their potential for nutrition applications.

Join me again next week for the next part of the tour – the South West is next!

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply