October 1, 2019, by Jonathan Memel

Finding Florence Nightingale Across the Atlantic – by Steph Meek

Steph Meek, an AHRC-funded PhD Researcher at the Universities of Exeter and Reading, recently discovered two previously unknown letters by Florence Nightingale during a research visit to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In the post below Steph explains how the letters shed light on the Victorian lending libraries to which Nightingale subscribed on behalf of the various institutions with which she was involved. Follow Steph on twitter @StephanieLMeek

Finding Florence Nightingale Across the Atlantic

by Steph Meek

When I embarked on my near 4,000-mile journey from Devon to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I did not expect to discover two previously unknown letters from Florence Nightingale. The aim of my research trip, funded by the South, West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership, was to explore the archive of Charles Edward Mudie, founder of Mudie’s Select Library (established in Bloomsbury 1842).

As I was handed the first five folders of the collection, I felt a mixture of excitement and trepidation. Would my finds justify my voyage across the Atlantic and increased carbon footprint? Mudie, however, did not disappoint.

The archive, situated in the University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, comprises eighty folders from Mudie’s correspondents; a family passport and travel diary of his 1860 tour of France and Italy with his wife Mary, their children and governess and a small collection of ephemera. Positioned at the heart of the Victorian book trade, Mudie was certainly well connected. The collection yielded a rich vein of correspondence from many notable figures within nineteenth-century arts and culture including Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, Elizabeth Gaskell, Harriet Beecher Stowe, George Cruikshank, William Ewart Gladstone, John Ruskin and Florence Nightingale.

A Rare Find

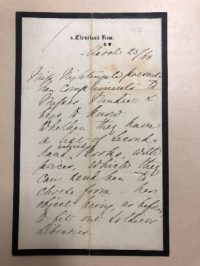

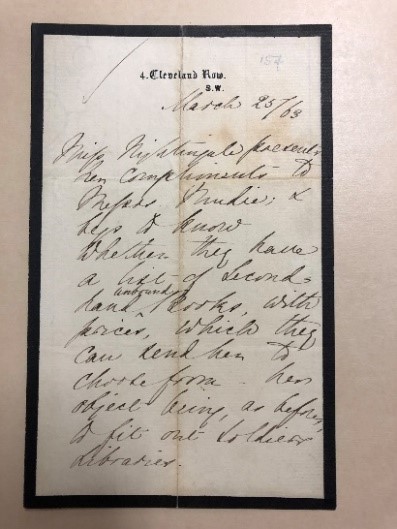

The archive holds two previously undiscovered letters from Florence Nightingale, dated 1863 and 1867 respectively. In the first, Nightingale inquires as to whether Mudie can supply ‘a list of second-hand unbound books….to fit out soldiers’ libraries.’ One of these libraries could possibly have been the new military hospital at Netley where Jane Shaw Stewart was appointed Superintendent General of Female Nurses in 1863. Nightingale’s wish to furnish these libraries with books specifically from Mudie’s chimes with her support for his institution. As Bostridge notes, ‘she preferred to take out one [a subscription] at Mudie’s for the Institution’s benefit, though not at its expense’ and had decided not to renew her subscription to the London Library on account of the fact that her literary preferences ‘are not to be found there’. Likewise, in another letter, this time to her sister Parthenope dated May 26 1859, she asks that she ‘create a run upon Mudie’ for Harriet Martineau’s For England and Her Soldiers (1859) and make everyone else ‘write to Mudie for it – We are told this is the way to make a book known – thro’ that “great fact” Mudie’ (Wellcome, MS 89988998/1) This is significant in that Martineau’s book was written at Nightingale’s instigation using her statistics, including the polar area graph. The urgency to publicise it attests to her feeling that the government had effectively tried to suppress some of the evidence that she was keen for the public to know about. Her patronage was mutually beneficial as Mudie’s circulation of second- hand books was an essential aspect of his trade in three-volume novels owing to the vast accumulation of stock once these hefty tomes were reissued in cheaper one-volume editions. According to William C. Preston, writing in Good Words in 1894, from approximately 1844 Mudie was exporting second-hand books around the world from Germany, Austria and Russia to South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

Nightingale to Mudie, 25 March 1863. Held at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

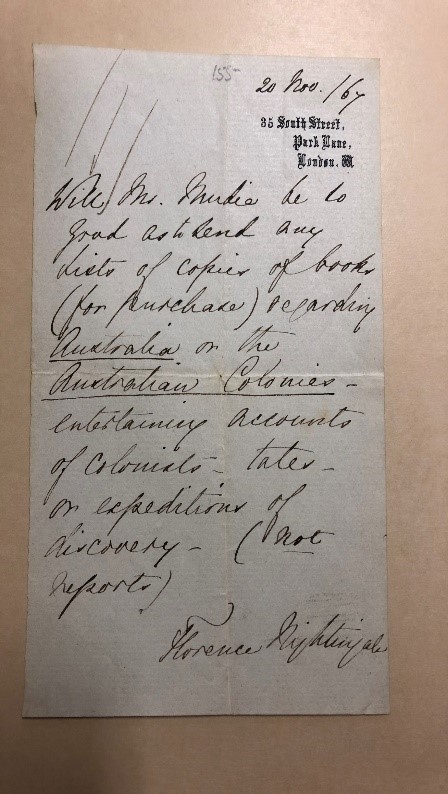

In her second letter to Mudie, Nightingale requests lists of books ‘regarding Australia or the Australian Colonies’ containing ‘entertaining accounts of colonials taken on expeditions of discovery.’ While it is tempting to assume that these books were intended for her personal use, it is almost certain that they accompanied Nightingale’s distant cousin Lucy Osburn and a team of five nurses to staff an infirmary in Sydney, Australia in December 1867. Either way, Nightingale’s emphasis on entertainment, rather than what she refers to as reports, reminds us of the recuperative power of reading.

November 20, 1867, The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Charles E. Mudie Papers, MSS 00042.

Finding Florence Nightingale across the Atlantic not only brought home the extent of Charles Mudie’s impact and influence as a lynchpin of the Victorian literary community but also the way that books and reading can touch many lives beyond the confines of a library.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Adam V. Dosky (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) and Nicola Wilson (University of Reading) for all their help and support in organising the trip. And to Jonathan Memel, Richard Bates (University of Nottingham) and Angelique Richardson (University of Exeter) for their input with this piece.

I am also grateful to the SWW DTP (South, West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership) for funding the visit.

Further reading

Mark Bostridge, Florence Nightingale: The Woman and Her Legend ( London: Penguin, 2009).

Judith Godden, Lucy Osburn, a lady displaced: Florence Nightingale’s Envoy to Australia (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2006).

Guinevere Griest, Mudie’s Circulating Library and the Victorian Novel (Indiana: Indiana University Press,1970).

Sharon Murphy, The British Soldier and His Libraries, c. 1822-1901 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)

W. C. Preston, ‘Mudie’s Library’, Good Words, 35, 1894, pp. 668-676. Retrieved from https://0-search-proquest-com.lib.exeter.ac.uk/docview/3320112?accountid=10792. Accessed June 6, 2018.

Iris Veysey, ‘A Statistical Campaign: Florence Nightingale and Harriet Martineau’s England and Her Soldiers’, Science Museum Group Journal, 5, Spring 2016, pp. <https://doi.org/10.15180/160504>.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply