July 8, 2021, by lqxag13

Winner of the 3rd Prize of the ENQUIRE Blog Competition 2021 – Brahmin Cultures of Disregard and Discard by Suraj Harsha

Growing up with my family, until the age of 24, I never had to clean a toilet. We lived in a chawl in Mumbai where every room of 100sq.ft was supposedly one family’s house but we were privileged to have two rooms to ourselves – a family of four. Built during the British rule for mill workers, we did not have a toilet inside our house, we had two toilets between five families (twelve rooms). A manual scavenger, who is still grossly underpaid starting with ~10 rupees (early 2000s) to ~ 80 rupees (presently) per month from each family used to clean the toilets and sweep the chawl, it was demanded that she do it everyday. Once a month, the toilets were to be cleaned with eye-burning and tear-inducing Hydrochloric acid or Bleaching powder, it only made it difficult to breathe. All the cleaning for our sanitation and hygiene was done without the consideration of the hygiene and sanitary conditions of the worker. Gloves, masks and boots cost way more than what she gets paid every month. On days when she was absent, the days were accounted for at the end of the month for deduction. Yearly, on the occasion of Diwali bonuses were a fractional amount of the month’s salary. We, tenants, were still unhappy and after much bickering about the coconut broom stick every month with complaints almost everyday, the payment was dropped – no touching – in her hands. The eldest women of all the houses including my mother were tasked to do this interaction with her.

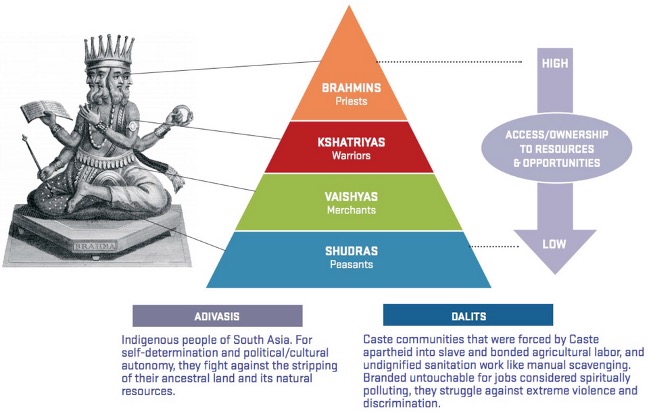

There were times when the workers were fired which for us only led to unclean and overflowing toilets. On days when the toilet would overflow with our own shit, which made it unbearable to breathe, we would wait for some worker to turn up the next day or make-do with it until it wasn’t overflowing. None of us took it upon ourselves to do what was needed. We were all Vaishyas. The thought of taking the initiative to clean the toilet was absent as this particular work of cleaning our discards was of other people – who were considered subhuman by us – a particular caste group, the caste groups who are structured outside the caste system rendering them not-human. The caste system is an intentional production of the Brahmins – the priestly caste groups in Hinduism. An organised and intentional disregard to those who are not only burdened but also mandated with our discards.

These practices are rooted in Brahmanism which is often ignored in studies on sanitation in urban areas. Consider (McFarlane, et. al 2014), which explores the process of sanitation and solidarities against the state while ignoring the centrality of caste. What turns out in this study is that the researchers’ respondents (tenants and political parties) blame the unhygienic and unliveable conditions on the cleaners’ ‘infrequent’ visits. All castes, whether rich or poor, employ manual scavengers to clean their toilet pits. The solidarity of the people, in actuality, does not build bonds with the manual scavengers who experience dehumanisation everyday. The institution of caste promises the impossibilities of solidarities. And as Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar rightly points out that the (caste)-Hindus do not have any sense of brotherhood towards them (Ambedkar, 1936, 2004). Evidently so, the demands by the residents to the state, in this study, is only to send the cleaner frequently and increase the number of toilets. However, the study succeeds in highlighting the unintentions of toilet-users to clean.

All manual scavengers (and safai karamcharis) be it employed by the municipal corporation or privately by residents are grossly underpaid and overworked. The state mirrors Brahmin cultures. In 2018, the BrihanMumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) denied ‘permanent status’ employment to its safai karamcharis and continued to bind them contractually. Between 2009 and 2015 more than 1,386 safai karamcharis who were employed by BMC died. A special cell was appointed to inspect the cause of deaths because the number of lives lost were very high.

The special cell was appointed only because the number of lives lost were very high. The state cultivates Brahmin cultures of disregard and discard which binds death onto these subjects. The idea of pollution is intrinsic to the institution of caste only because the caste that enjoys the highest rank is the priestly caste: while we know that priests and purity are old associates (Ambedkar, 1917, 1979). It is then, as per Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s (ibid.) conclusion that castes were formed and practiced by imitation of higher (Brahmin) by lower, however, not voluntary or conscious. Thus, even us, non-Brahmin caste-Hindus, want our surroundings to be clean, sometimes even ‘beautified’.

Brahmin cultures have the potential to penetrate even international borders. As Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in his seminal work, ‘Castes in India (1917)’ states, “[caste] is a local problem, but one capable of much wider mischief, for “as long as caste in India does exist, Hindus will hardly intermarry or have any social intercourse with outsiders; and if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, Indian caste would become a world problem” (Ketkar, Caste, p.4)”. The Dalit Solidarity Network United Kingdom (DSNUK) has been working for equal rights to Dalit people in UK and most importantly advocating for ‘caste’ as a protected category in the Equalities Act, 2010. As per their estimation 4.5mn South Asians and other communities in UK belong to or are attributed to a caste. The UK government also commissioned a report in 2010 titled, ‘Caste Discrimination and Harassment in Great Briton’ which signifies caste as a social issue in UK and elsewhere. The report also mentions (pp 33-36, 39, 53 and elsewhere) about how people from the ‘upper’ caste at workplace would use casteist slurs, hinder promotion and assign humiliating work all to remind ‘lower’ caste people that they are below them. In one such case, an ‘upper’ caste person reminded a ‘lower’ caste person that their duty is to wash the floor. In places of worship, ‘upper’ caste people did not allow ‘lower’ caste people near the god.

Brahmin cultures name impurities to distance themselves from dirt. In order to maintain their ‘purity’, for instance, by vegetarianism, Brahmins distance themselves from animal products except milk. The Brahmin cultures sustain disregarding and discarding through the practice of distancing. The spatiality of waste then rests on this culture. Anthropogeographic studies could help visiblise that the spatiality of discards and people from the outcast groups are often shared. Both the waste and dehumanised people are distanced from the vantage of Brahmanism. Thus, the discarded waste is made to stick/attached to the disregarded community. The distance is now maintained with the waste and the group of people thus also burdened the community to deal with the waste. And when the community decides to not deal with the waste. The waste remains as is, with no intentions to touch by caste-Hindus (NDTV, 2016). Cleanliness in Brahmin cultures is not by being accountable for one’s waste produced but rather pushing away the waste onto someone else. It holds no concerned intention to be responsible for accumulation, consumption and discard.

Suraj Harsha (Independent researcher, BA in Sociology from University of Mumbai and M.A. in Sociology and Social Anthropology from Tata Institute of Social Sciences)

Email: researchsurkee@gmail.com

Twitter: qtpa2tea

Ambedkar, BR (1917). Castes in India: Their Mechanisms, Genesis & Development. Indian Antiquary Vol.XLI.

Ambedkar, BR (1936). Conversion as Emancipation. New Delhi: Critical Quest (2004).

Ambedkar, BR (1979). Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Vol. 1 pp. 3-22. Vasant Moon (ed.). Bombay: Education Department, Government of Maharashtra.

Bordia, R. (2016). After Una Violence, Gujarat’s Dalits Strike Back, Won’t Remove Dead Cows. NDTV.com

Colin McFarlane, Renu Desai & Steve Graham (2014) Informal Urban Sanitation: Everyday Life, Poverty, and Comparison, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104:5, 989-1011.

Image featured: Caste is a structure of oppression that affects over 1 billion people across the world (Equality Labs)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply