April 11, 2017, by Matt Davies

Notes on the School of Humanities slide collection part two by Nicholas Alfrey

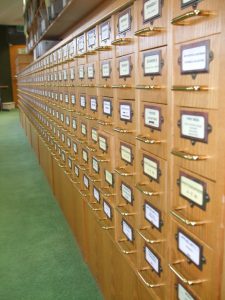

The slide collection in the History of Art department’s old home at the Lakeside Arts Centre. Photo by M Davies.

In the second part of Notes on the School of Humanities slide collection, Nicholas Alfrey looks at the contents of the collection and what it tells us about the way History of Art has been taught at Nottingham over past decades.

As will be evident to anyone who has spent time browsing through the slide cabinets now housed in DHC, there are whole sections which have no obvious didactic purpose. There are records of exhibitions organized by the University Art Gallery, for example, invaluable in their own right as documentation. And there are some sets eccentric enough to make it hard to guess what purpose they could have served. Others entered the collection as donations: there is a group relating to the Trent and other regional rivers, for example, in which some of the images have been produced by long-discontinued means of colour processing. The largest donation came from the architect Alec Daykin (1918-2010), who gave his architectural drawings to the University of Sheffield, where he had studied and where he later taught, and his extensive collection of slides of sites and buildings to Nottingham. Daykin had a special interest in the ancient world, and served as architect and surveyor on several archaeological expeditions.

The more straightforward art historical materials in the collection are of interest not least because they prompt reflections on the slide as a medium in its own right, a medium which conditioned the teaching of art history itself. Typically, the art history lecture would involve twin projection, so that exposition depended essentially on a comparative method, with images shown side by side to bring out patterns of affinity, influence or difference, or with details shown for telling effect alongside a complete composition. True, comparison is often the basis of PowerPoint presentation as well, and the new technology now permits the juxtaposition of multiple images or sources in a single frame. But a PowerPoint presentation has none of the immersive quality of a double screen slide-show, since on only a single screen the images are necessarily much reduced in scale and presence. This is compounded by the tendency to accompany images with text, reducing the image to just one element in a field of information, visual and verbal. There are obvious advantages to this when it comes to conveying information – artists’ names, titles dates, medium and so on. With a slide lecture, this kind of information would have to be conveyed by other means. Arguably, though, slides enabled the presentation of images with a vividness and integrity which has been compromised in the new technology, for all its efficiency gains.

Twin slide projectors in History of Art’s one time seminar room at the Lakeside Arts Centre, with the DH. Lawrence Pavilion in the background. Photo by M Davies.

This is not to claim that slides are a ‘better’ replica of the works of art they reproduced than a digital image. From a technical point of view they were quite often inadequate, and they could also be subject to deterioration, so that even a high quality image, if developed on unstable stock, could gradually turn a ghastly shade of pink. (Admittedly most of the worst cases have already been weeded from the collection by volunteers). But a slide collection like this can tell us a great deal about how the history of art has been mediated. And we can really only appreciate how this works now that slides are no longer our main conduit to past artistic production.

It wasn’t only art historians who invested so much in slides: artists too have made use of them, and not just as a means of documenting their work. (There are, though, a number of instances in the collection of the medium being used in this way, most of them relating to the Artist in Residence scheme that was at one time sponsored by the University). But artists have sometimes used slides directly as a means of creative expression, such as Robert Smithson in his Hotel Palenque (1969) or Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985). In 2005, the Baltimore Museum of Art organized an exhibition devoted to the theme called SlideShow: Projected Images in Contemporary Art. The date of the exhibition is significant: it came a few months after Kodak announced that they would no longer be manufacturing 35mm slide projectors, and that slides had therefore become an obsolete visual technology. This very circumstance, however, has made a new generation of artists all the more keen to make use of them.

Nicholas very kindly spoke about the Humanities slide collection at the recent private view for DHC’s ‘Then and Now’ exhibition which featured slides of Nottinghamshire from the aforementioned architecture section, projected besides digital images of the same buildings and spaces as they are now. To see photos from the preview event and installation shots visit our Flickr page here, and look out for a news blog on the exhibition coming up soon.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply