October 9, 2015, by Charlotte Anscombe

Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners

Katie Donington is currently a Research Associate on the Antislavery Usable Past project in the Department of American and Canadian Studies at The University of Nottingham, and is Co-director of the Centre for Research in Race and Rights. In this blog, she looks forward to an upcoming event with David Olusoga on Monday 12 October.

No it isn’t easy to forget

What we refuse to remember

Grace Nichols, ‘Taint’ in I is a long memoried woman (1983)

What do we chose to remember? What do we try to forget? History writing is as much a process of forgetting as remembering – the inclusions and omissions reveal the ways in which we think about ourselves, and the ways we would wish other people to perceive us. As Guyanese poet Grace Nichols points out – memory-work is an active process. The history of slavery is often told through the lens of abolition. The role of emancipator fits comfortably with the idea of Britain as a liberal, freedom-loving democratic nation. Historian and broadcaster David Olusoga has recently pointed out that whilst there are many monuments dedicated to the Britons who abolished slavery, there is no permanent public memorial to the enslaved people of the Caribbean in the capital city. As David writes ‘The slaves have not been cast in bronze but cast into obscurity; their faces and their chains are reminders of a history the nation has done its best to forget.’ But how can we tell the story of abolition without first telling the story of enslavement? What is at stake when we refuse to remember the traumatic history of transatlantic slavery? David Cameron’s recent trade visit to Jamaica has been overshadowed by the still raw memory of slavery and the vexed issue of reparations. During a speech he acknowledged that ‘these wounds run very deep’ but urged Jamaicans to ‘move on from this painful legacy.’ For the people of the Caribbean it is a near impossible task to forget – slavery is inscribed in the landscape, the street signs and even in their own names.

Mural painted on the walls of Liberty Hall in Kingston, Jamaica. When Marcus Garvey was deported from the USA to Jamaica in 1927, Liberty Hall became the worldwide headquarters of the United Negro Improvement Association. It is now a library, museum and education centre. Image © Katie Donington

To mark Black History Month, I will be taking part in an event with broadcaster and historian David Olusoga and Dr Susanne Seymour from the Department of Geography, co-organised by the Centre for Research in Race and Rights. We will be discussing the making of the documentary Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners. The two-part programme was the result of a partnership between the BBC and the Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London. I spent six years working for the project firstly as a PhD student and later as a researcher looking at the history of slave-ownership in Jamaica. The project used the forgotten history of the slave-owners as a way into thinking about how slavery and the enslaved contributed towards the making of modern Britain.

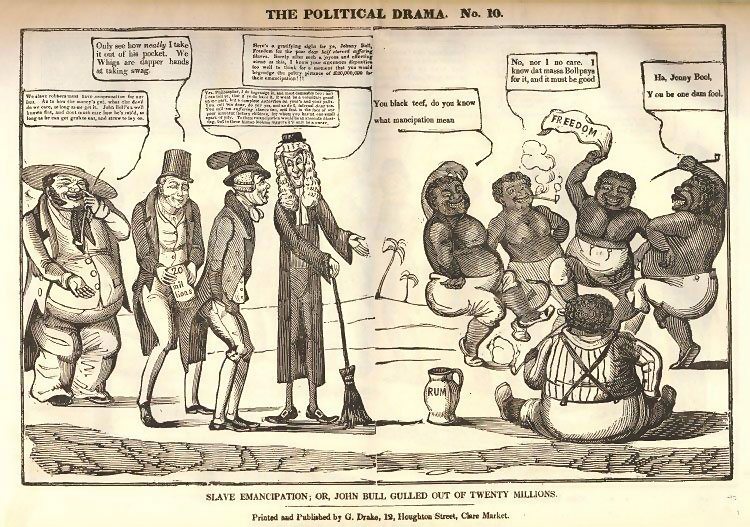

The Legacies project digitised the records of the slavery compensation commission. As part of the measures taken to end slavery in the Caribbean, the British government agreed to pay the slave-owners £20 million compensation for their ‘property in people.’ This process created a bureaucratic record of everyone who claimed ownership in enslaved people at the ending of slavery in 1834. There were approximately 46,000 claimants, of those people the project focused on the absentees – people who owned enslaved people but who lived in Britain. This created a universe of around 3000 people for whom individual biographies were written by the team. The project used different legacy strands to try and measure the impact that these people had on the shaping of different aspects of Victorian society. It looked at their activities as commercial, political, cultural and social actors, their involvement in other areas of empire and the physical traces they left behind, for example, country houses. The project also examined the ways in which these former slave-owners thought and wrote about the West Indies and how these representations shaped perhaps the most pernicious legacy of slavery – racism.

To make a claim the slave-owners had to provide details of where they lived in Britain, this means that the Legacies database can be searched by geographic area making it a useful tool for people interested in local history. Susanne Seymour has worked extensively on the connections between the Midlands, slavery, and colonialism more broadly. Her work has combined the database of slave-owners with different kinds of relationships to the slavery business. She has looked at links to the cotton industry, the sugar trade, slave trading and the historic black presence. Both Susanne’s work and that of the Legacies project is designed to close the distance – both geographic and psychological – between the Caribbean and Britain, between the past and the present. In bringing the history of slavery home this work asks important questions about history, memory and identity; about what it meant, and indeed what it continues to mean to be British.

Britain’s Forgotten Slave-owners is taking place on Monday 12 October (6.30-8.15pm) at A30 Lecture Theatre, Nottingham Lakeside Arts, University Park Campus, University of Nottingham. You can book your place online.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply