July 25, 2013, by Nicola Royan

Comparing technologies of publication

About five and a half centuries ago, printing with moveable type became possible, a result of Johannes Gutenberg’s inventiveness, but also because the necessary materials, including the right kinds of metal to make type, became available. Over the subsequent fifty years or so, this technology spread and became commercially viable: more printed books circulated, especially in such high use areas as grammar school rooms, churches and, certainly by the later sixteenth century, the street, in the form of pamphlets. We are at the moment enjoying a similar change in technology for reading, where digital publication, whether as e-books or PDFs or webpages, appears less expensive, and to have a much greater circulation than print, and where the demise of the codex, that workhorse form of the book with which we are all familiar, is routinely predicted.

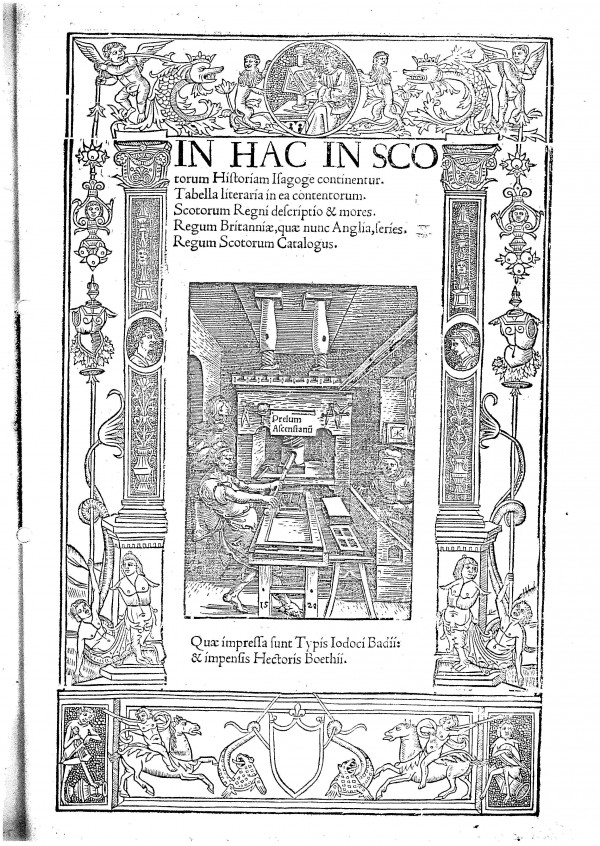

I was pondering that earlier technological change at the Early Book Society conference in St Andrews earlier this month (http://www.nyu.edu/projects/EBS/). My current research is considering the reception of humanism (in short, the rediscovery of classical Latin and Greek texts as material to be replicated and re-presented, particularly in the forms of language) in early sixteenth century Scotland. My period of interest corresponds almost exactly to the first appearance of print in Scotland, for although the first Scottish printing press, run by Walter Chepman and Andro Myllar , (http://digital.nls.uk/firstscottishbooks/) was only in business for around ten years, many printed books were imported from the continent, especially but not exclusively from Paris, and quite a few Scottish books (always in Latin) were printed there too.

And yet despite the growth of print, it did not displace immediately displace manuscripts. Until very recently, of course, and the development of portable and quiet means of typing, note-taking was of course almost invariably handwritten; but in addition to this, manuscripts were produced both professionally to order and privately for personal or family interest throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Some figures, like Sir Philip Sidney, considered print as rather vulgar, and circulated their own material in manuscript. Marie Maitland, in the 1570s, appears to have collected particular poems into a single manuscript as a tribute to her father, Sir Richard. More commonly, print versions seem to have had a particular attraction as reliable and easy-to-read exemplars, from which scribes could make their own copies: this is a practice we see in the Asloan Manuscript (c. 1513; Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland MS 16500), into which John Asloan looks to have copied texts from Chepman and Myllar prints. Asloan is certainly not unique in this use of print.

Reflecting on the slow and still incomplete substitution of print for manuscript made me reflect on the pace of our current technological change. In some ways, it seems extraordinarily fast: just thinking about the shrinking of mobile phone sizes over thirty years indicates that. On the other hand, print and indeed manuscript still have their place: a publisher observed to me that while a contemporary academic’s office may contain fewer books than it would have done fifty years ago, it has significantly more piles of A4 print-offs. This state of affairs is surely analogous to using print editions as exemplars for manuscripts: print, the hard copy, the codex and even handwritten notes are not dead yet!

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply