March 18, 2013, by Christina Lee

Deadly companions: a world without antibiotics

In the wake of headlines telling us about the imminent threat of antibiotic resistance I had to think about my own research on the impact of epidemics on early medieval societies. The medieval period can clearly show us what a world without effective antibiotics could be like. When the Middle Ages are portrayed in popular shows and fiction, it is as a time of war and brutality, but while wars occurred frequently, the most significant threat to medieval life was invisible: microbes, bacteria and viruses which would haunt populations time and again.

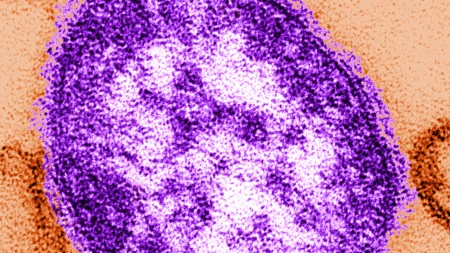

Most of us are familiar with the fourteenth century Black Death, but few know about the other waves of infection which swept across the British Isles: smallpox, tuberculosis, leprosy and Yersinia pestis – the same microbacterium that causes the plague (although we have had a few mutations). Pathogens were not the threat to life – infection could also result from open wounds and therefore in this world without antibiotics child birth was often lethal, as were work accidents resulting in cuts and wounds. Text sources and some archaeological data shows us that Anglo-Saxon leeches could set bones and even restore a person with multiple fractures, but they could do nothing against bacteria.

The terror caused by epidemics comes through loud and clear in historical writings. For example, the Venerable Bede tells us in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People that a plague devastated large areas of England in AD664, which was so bad that the East Saxons returned to paganism. Apocryphal sources tell us that by 665 the plague was so bad that people threw themselves off cliffs to rather have a swift death than to have to endure the pains of the plague. Saints such as St Cuthbert went out to administer to those who were dying in great pains. While chroniclers are not medics, they can give us some ideas of the symptoms: swellings, tumors and fevers. Bede tells us that in 446 a terrible plague devastated the Britons, so violent that the living could no longer bury the dead. While Bede’s narrative is often didactic (after all, he needs to make a case for why the Anglo-Saxons had to invade the country) and steeped in classical plague narratives, geneticists have started to find connections between early medieval narratives and outbreaks of epidemics. For example, the Justinian Plague (AD 541-2), is now thought to have steadily crept northwards, and we can charter its course in the writings of Gregory of Tours, Bede and the Irish annals.

Diseases could not only affect humans, but also animals. The chronicles are full of narratives of infectious disease that affect cattle, as well as occasional ‘mortality of bees’. These epidemics would have had great economical impact on the largely agrarian societies of Britain and Ireland. Famine often follows cattle disease, and this in turn would have weakened populations. Just as today, people wanted to know the causes for disease. A wide-spread error is the modern arrogance that we are much more intelligent than people in the past. I am sure that a man like Bede with a burning curiosity for the world around him (todays science – he wrote about the nature of things) with contemporary equipment would be a Nobel Prize winner. In the absence of microscopes and centrifuges, medieval people tried to detect causalities between the epidemics and other visible things, such as clouds, stars and comets. Not all of them scientific, but we can see that when diseases are associated with supernatural phenomena, such as dragons, they are referring to an airborne transmission. I think that it is often us who do not understand the language that medieval people used to describe the world around them. You call it pathogen, I call it dragon.[1]

[1] An interesting link has been made by Peregrine Horden, Disease, dragons and saints: the management of epidemics in the Dark Ages’, in: Epidemics and Ideas ed. T. Ranger and P. Slack. CUP: 1995, 45-78.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply