October 31, 2019, by Kathryn Steenson

The Witches of East Mids

Early Modern European society is notorious for its waves of enthusiastic witch-hunts. The causes have been debated by historians, but they were almost always a combination of religious, societal and economic upheaval and uncertainty.

Powers commonly ascribed to witches include turning food inedible, flying, and making people and livestock ill and crops fail. Witches were not always seen as evil: in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, ‘cunning men and women’ were often consulted for their alleged healing abilities, folk medicine cures, and occasional divination. Witches were not always women, but older women could be more vulnerable to accusations because they were more likely to be dependent on the community and less likely to have influential defenders.

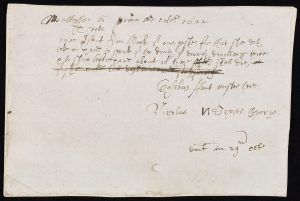

Churchwarden presentment for soothsaying, Mattersey, Retford deanery; 1 October 1622

Ref: AN/PB 339/3/92

This says “Minister and one churchwarden present the following: Anne Cook of our parish for taking in hand to speak of the death of divers [people] dwelling therein, and to show beforehand about what time they shall die [‘as of shee could tell destinies and soothsayinges’, crossed out].” In other words Anne was in trouble for telling people’s fortunes, and in particular predicting when they would die, and it’s easy to imagine why this might unsettle some of her neighbours.

Witchcraft, soothsaying and other superstitious practices came under the remit of the ecclesiastical courts. Despite the impression many people have of widespread persecution and killing of witches, this wasn’t the case with the vast majority of accusations. Where no harm had been caused – that is, people sought or provided healing or fortune-telling – the church would require the offender to publicly repent, and cease the behaviour, which is likely what happened to Anne Cook when she came before the court (there is no information as to whether her prophecies were accurate).

The Bakewell Witches, Bygone Derbyshire, edited by William Andrews; 1892

Ref: East Midlands Collection Der 1.D14 AND

Probably more famous for its puddings than as a hotbed of sorcery, this gives two accounts of what happened to Mrs Stafford, a milliner from Bakewell, and her un-named sister, the ‘Bakewell Witches’.

In 1608, an itinerant Scottish man, whose name is also not recorded, was discovered half-dressed in a London cellar by a night watchman. Facing felony charges, he came up with a bizarre defence to explain both his presence and his unclothed state: that he had been spirited there by witches.

He had been lodging with Mrs Stafford in Bakewell, and late one night had witnessed her and her sister conduct a ritual and chant “Over thick, over thin / Now, devil, to the cellar in Lunnun” and immediately disappear.

Full of curiosity, bravery or foolhardiness, he repeated the incantation. He was whirled through the air and transported to the cellar, where the two witches offered him some wine that immediately rendered him unconscious. Unfortunately for the women, the authorities in London and Derbyshire gave this story far more credence than it deserved. The discovery of his clothes in Bakewell condemned them to the gallows.

The far more plausible story is that Mrs Stafford evicted her lodger after he fell behind with his rent, and kept some of his possessions in lieu of payment. With no money and nothing but the clothes on his back to sell, he had travelled to London. A charitable interpretation is that he sought shelter in an unoccupied building overnight; the more cynical is that the night watchman interrupted a burglary, and the Scot’s defence both saved his own neck and got revenge on his former landlady.

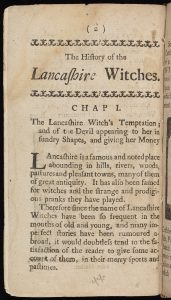

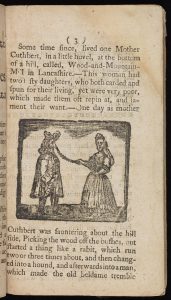

To end on something a little lighter, the fictional tale of ‘The Lancashire Witches: containing their manner of becoming such: their enchantments, spells, revels, merry pranks, raising storm and tempests riding on winds &c.: the entertainments and frolick which have happened among them conducive to mirth and recreation’ (18th century, ref: EMSC Not 3.Y14 LAN). The protagonists are a poverty-stricken woman, Mother Cuthbert, and her daughters Margery and Cecily. The trio are persuaded to become witches after an encounter with a shape-shifting hare and a square meal. It is less of a single coherent narrative and more a recitation of loosely-connected events. The description ‘merry pranks conducive to mirth’ is somewhat of a stretch, as the witches mainly use their powers to transform into animals and take petty weather-based revenge against former sweethearts for small slights. Despite being servants of the devil, they are surprisingly moral at times, in one instance freeing a debtor from the custody of the bailiffs, and later returning stolen property to a poor family.

The documents and books mentioned here are available to see in our Reading Room at Manuscripts & Special Collections. More information about our holdings and the online catalogues is available from our website, newsletter or @mssUninott.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply