August 20, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

A Token of Childhood

Are the souls of your children of no value? Are you indifferent whether they be damned or saved? They are not too little to die…not too little to go to hell….not too little to go to heaven.

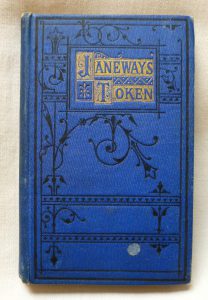

And so begins James Janeway’s cheerful book, ‘A Token For Children: An Exact Account of the Conversion, Holy and Exemplary Lives, and Joyful Deaths of several Young Children’. It does exactly what the title threatens: recounts the pious lives and actually quite tragic deaths of 13 children, whose ages range from toddlers to teenagers.

James Janeway (1636–1674) was a Puritan minister and author, and his wider theological ideas were very influential on Puritan thought. He held the then-widespread belief that every child was born sinful and had a natural tendency towards wickedness. This book was an attempt to save their souls by providing Godly examples intended to inspire his juvenile readers. Janeway encouraged parents to give the book to their children, assuring them that

“What is presented, is faithfully taken from experienced, solid christians…of unspotted reputation, for holiness, integrity, and wisdom; and several passages are taken verbatim in writing from their dying lips”.

The protagonists are all extremely devout children who pray many times a day, weeping over normal, petty misbehaviour as though they had committed the most heinous of sins, and generally existing in a near-constant state of anxious misery. After establishing this backstory, Janeway has them succumb to illnesses over a period of days or weeks – always borne without complaint or fear – and on their deathbeds they earnestly entreat their friends and families to be good Christians and reaffirm that their faith allows them to face death without fear, in the certainty that they are going to a better place.

The children are probably fictitious, but the biographies are not as unrealistic as they may first appear. In 1671 when the book was first published, church attendance was compulsory and most of the population believed Heaven and Hell were literal places. Clergy and parents did not shy away from discussing death. How could they, when one in three children would die before the age of 16? Many children who read this book would have lost a sibling or a playmate, if not a parent. People often died at home, having been nursed by family and neighbours, and would remain there until the burial.

Within this context, it is not surprising that some children responded with a kind of precocious piety. Contemporary diaries and letters show that parents tried to comfort a dangerously ill child (and on some level, themselves) by talking about faith in God and reuniting with loved ones in the afterlife. This was the horrific reality of childhood in the 17th and 18th century.

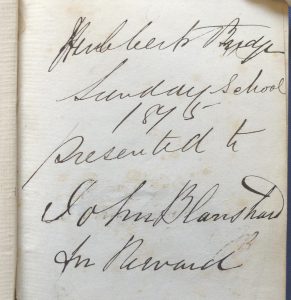

‘A Token for Children’ remained in print for over 200 years and its popularity ensured that Janeway was one of the most widely-read children’s authors in the English-speaking world. Copies were given as prizes in Sunday School in the 19th century, so the message of the book clearly held an enduring appeal for adults. Despite the grim subject matter, memoirs and letters express a fondness for the book by those who read it in childhood. Perhaps children enjoyed it in a macabre way, much as they’d read Foxe’s Book of Martyrs for all the gory deaths, or perhaps they genuinely took comfort from it.

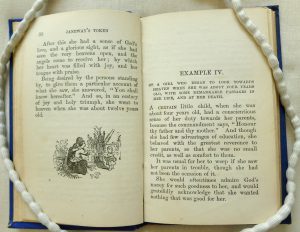

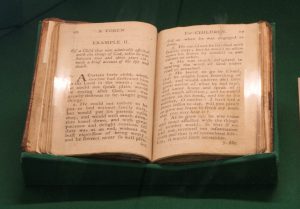

We hold two copies, one published in about 1800 and the other in 1830. These later editions included prayers and added pictures that weren’t present in the first edition.The earlier volume is currently on display in the Weston Gallery as part of the exhibition From Rags to Witches: the grim tale of children’s stories, which runs until the 26th August, but the other can be viewed in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room. For more information about our holdings or exhibitions, follow us @mssUniNott or read our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply