August 15, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Silence

The grumpy 13th century scribe who couldn’t help but open his story by reminding his audience how underpaid and underappreciated the arts (especially storytellers) are would probably despair if he had known similar complaints would still be expressed in the 21st century.

He wrote seven centuries ago, but his tale was set seven centuries before that, in around the 6th century AD. Cador – knight, heir to the Earl of Cornwall, and kinsman of King Arthur – bravely slays a dragon and wins the hand of the woman he loves. Together they have a son, Silence. Or do they?

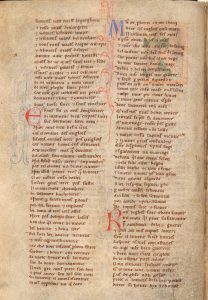

Master Heldris of Cornwall pictured in the collection of French romances and fabliaux, c.1275, folio 188

No. (Apologies to people who dislike spoilers, but you have had 700 years to catch up). Silence is a daughter, born in an era where women can’t inherit wealth, property or power. Raised as a boy in relative isolation, he doesn’t find out the truth until adolescence. He chooses to keep up the pretense despite being troubled by the conflict between nature and nurture. Eventually he runs away with minstrels and ends up a knight in the royal court. The queen schemes to have Silence banished to France and executed after he spurns her adulterous advances. There, his chivalry, valour and skill earn him the protection of his royal patron, but when war breaks out in England, Silence is summoned back to fight for the king. Enraged, the queen orchestrates what she believes to be an impossible task: capturing the wizard Merlin.

This final act of jealousy and wickedness is her downfall: Silence takes Merlin prisoner, who then reveals before the royal court that Silence is a woman and that the queen has a male lover who cross-dresses to disguise himself as a nun. The king has his unfaithful wife and her lover executed and marries Silence, who chooses to live as her biological gender.

WLC/LM/6 in bespoke archive packaging, in its latest, and hopefully permanent, home at the University of Nottingham. Next to it is an early 15th century volume also from Wollaton Hall.

It’s a ripping yarn combining love, war, and cross-dressing, and one that has attracted the attention of scholars of history, literature, and gender, and more recently, of storytellers and radio documentary makers. And for them, the story of the story was as interesting as the plot itself.

Le Roman de Silence is one of 18 romances (heroic prose tales) and fabliaux (comic, bawdy tales) within a volume, WLC/LM/6, written in the Picard dialect of Northern France sometime in the early 13th century. It could have been brought to England following the looting of the Chateau de Laval in 1428, during the Hundred Years War. The only clue to its early ownership is a 15th-century inscription on the last page, reading ‘John Bertrem de Thorp Kilton’. He died without heirs in 1471, and at some point thereafter the volume passed into the library of the Willoughby family of Wollaton Hall in Nottingham.

It is a beautiful volume. The texts are illustrated by 83 miniatures, 14 of which accompany Le Roman de Silence. This is unusual for medieval French vernacular manuscripts although it was common for religious texts to be illustrated. Here we have at least two people (one definitely more artistically adept than the other) augmenting the columns of text with flourishes of red and blue inks, as shown in the image.

What was also interesting was how different a narrative the two groups built around it. For the BBC Radio 3 team, it was a case of the manuscript bursting forth from its hiding place when the moment was right, that fate had led to its (re)discovery at the time when questions about gender, nature and nurture were being raised. For storyteller Rachel Rose Reid, it was the opposite: the women’s suffrage movement was growing and it was far too dangerous to allow a story about a cross-dressing, capable woman to be told.

The truth, as always, lies sedately in the middle. The Historical Manuscripts Commission (part of The National Archives since 2003) was set up in 1869 to locate and record private papers of historical interest and to advise on preservation, storage and access. In 1911, W H Stevenson from the HMC visited Wollaton Hall to survey the archives of Lord and Lady Middleton. The final report (full text also available online) ended up being over 600 pages, cataloguing and in some cases calendaring the deeds, court rolls, letters, and literary works in the muniment room, a fireproof room in basement of Wollaton Hall.

It is true that the story lay unappreciated and largely forgotten for several centuries. This wasn’t always the case, as at some stage the illustrations were protected with silk and the sewing holes are still visible. The silk was likely gone by the time a rough catalogue of the Wollaton archives was compiled between 1784 and 1794. Some 40 or 50 years later the older manuscripts and books were packed into about 300 large parcels, seemingly at random, many being labelled as ‘illegible’ or ‘of no value’. Today this might seem odd, but that’s a projection of fairly recent modern values about conservation – old books were routinely disbound and their pages used to cover other books, which is often the only reason those fragments survived. Think of how many towns demolished medieval and historic buildings in the 1960s to make way for the new concrete future.

Silence as a child between two minstrels, the image discussed in the BBC radio documentary, from a collection of French romances and fabliaux, c.1275, folio 203 recto

Stevenson was a scholar and a librarian and recognised an important medieval manuscript when he found one. The main body of the report describes the volume as ‘stout’, measuring about 8 inches by 12. Le Roman de Silence was a poem of 6500 octosyllabic lines and the genealogy of Cador was evidently based upon the pseudo-historical work Historia regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth (c.1095-c.1155). In the introduction to the report, he highlighted it as noteworthy, commenting that the author of Le Roman de Silence, one Heldris of Cornwall, was hitherto unknown. It would not be until 1927 that anyone realised that this was the only complete copy of this poem in the world.

Part one of the BBC’s ‘Binary and Beyond’ is available on iplayer (Roman de Silence is mentioned from about 10m15s in a discussion about how gender is portrayed in art). More information about Rachel Rose Reid’s storytelling performances of Silence is available on her website. It was one of several volumes in the Wollaton Library Collection of medieval literary manuscripts now at Manuscripts and Special Collections, King’s Meadow Campus, and a digital version is available to consult in the Reading Room. More information about it is available from our website.

Thank you Kathryn! Great to discover this blog!