October 20, 2016, by Kathryn Steenson

Fragments of a Saint

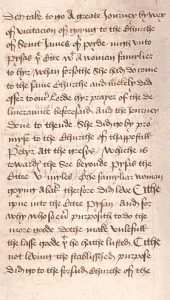

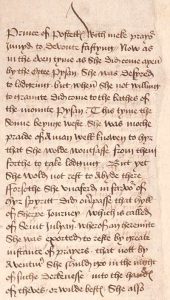

Tucked away in a bundle of 17th century natural history illustrations was a single page of comparatively plain-looking handwritten text that was obviously out of place. It began abruptly in the middle of a sentence and the edges were slightly more battered- not surprising, considering it was about 200 years older than the rest of the pages. This single leaf of paper is the only surviving evidence of a medieval English vernacular translation of the life of St Zita of Lucca, Italy.

Patron Saint of Servants

Zita (also known as Sitha or Cithe in England) was born in Tuscony in about 1212 to a deeply religious family. Her elder sister had already become a nun by the time a 12-year old Zita was sent to work as a maid for a wealthy family of weavers, the Fatinellis. She was mistreated by her employers and fellow servants, but Zita believed her place in life had been given to her by God, and that by remaining obedient, pious and loyal, she was doing God’s work.

Each day she woke early to pray and attend Mass before starting her household chores. One story claims that one day she was so engrossed in her religious devotions that she was late returning home to bake bread for the family. On rushing to the kitchen she discovered the unbaked loaves neatly lined up, ready for the oven, having been prepared by angels. As apocryphal stories go, it’s fairly heavy-handed in its message, but it is true that eventually Zita’s patience and hard-work were recognised and rewarded. When she died in 1272 – still working for the Fatinellis – she was much-loved and respected. Multiple miracles were attributed to her, most frequently in connection to her feeding and clothing the poor, and she was canonized in 1696.

Every journey begins with a single….toe?

Her cult was spread across Europe by Italian merchants and traders. Her popularity reached its peak in England in 1456 when a piece of her hair and her little toe were -allegedly – brought to the Knights Hospitaller’s church at Eagle, Lincolnshire, which then became a place of pilgrimage. Several churches in the East Midlands have or had altars, stained glass, or statues dedicated to her. She was particularly popular with housewives and servants, undoubtedly because they could relate to a hard life of unappreciated drudgery. Given Zita’s reputation for unquestioning devotion to her work, employers were probably quite happy to hold her up as an example for their servants.

The Knights Hospitaller house at Eagle was dissolved in about 1540 during the Reformation, and the practice of displaying relics became extremely uncommon in the new Protestant era. The whereabouts of the toe, and if it truly did belong to the saint, are unknown. Her body is mummified and on display in the Basilica di San Frediano in Lucca, so it ought to be possible to see if she is indeed missing a toe.

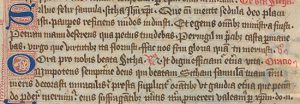

St Zita features in another 15th century manuscript, a prayer book containing many prayers (in Latin) to the Virgin Mary and saints associated with East Anglia. It is a more attractive manuscript than the fragment, with leaves and flowers decorating the borders, and the different parts of the text have been delineated with decorative initial letters in blue and red ink.

A Fragmented Life

This Middle English text dates from about 1450-1475 and is a literal translation of the Latin ‘Life’, a biography written a century after her death. The passage describes Zita’s pilgrimage to churches near Pisa, travelling many miles to pray, refusing all food and lodging offered to her by friends and even a holy hermit, such was her fervour of spirit.

Higher quality images and transcriptions and translations of these manuscripts are available online as part of an online exhibition on the lives of medieval women: Wives, Widows and Wimples. The fragment (WLC/LM/37) and the prayer book (WLC/LM/11) are now part of the Wollaton Library Collection at Manuscripts & Special Collections. Due to their sensitivity to environmental conditions, it isn’t always possible to produce the originals in the Reading Room. However, they have been digitised and can be viewed on a dedicated terminal in the Reading Room. Email us to make an appointment, or for general information see our website, follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott, or read our newsletter Discover.

Some of our medieval documents are on display as part of The University of Nottingham Museum‘s display The Medieval World in Colour at Lakeside Arts until 18th June.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply