July 15, 2013, by Kathryn Steenson

All Work and No Play

Students using the Business Library over the summer exam season may, whilst taking a small break from revising, have noticed the display has changed from the subject of electricity to one probably closer to their hearts: the harsh reality of working life (albeit for children in the 18th and 19th centuries). The concept of childhood we have today is largely a modern construct. During the Industrial Revolution it was usual for adults to work 16 hour shifts, six days a week. For the poor, even this did not pay enough to support the family. As soon as children could walk and talk, they were expected to work.

The legislation to curb child labour was piecemeal, with labour laws only applying to certain industries. The first Factory Act attempting to regulate and improve conditions was passed by Parliament in 1802. It stipulated that children aged 11-18 in cotton mills could work a maximum of 12 hours a day, and no child under the age of nine was to be employed. Cotton mills were forbidden to employ children at night from 1831; the rest of the textile industry followed in 1833. Although compulsory elementary education was not introduced until 1870, from 1833 children aged 9 to 13 working in textile mills had two hours schooling per day, on top of their shift. It is doubtful how much they learnt.

This extract from a report (Ref Bo X 1) into the bobbin net trade from the papers of Boden and Company Ltd, recounting an inspection of the factory, illustrates the opposition that faced labour reform. It expressed concerns about the impact that prohibiting persons under the age of 18 from night-work would have (on profits, not on the children). It concluded that the children did ‘not appear…to require legislative protection either by reason of the intensity or duration of their labour’. Nevertheless, maximum working hours for women and children were lowered to ten in 1848.

This extract from a report (Ref Bo X 1) into the bobbin net trade from the papers of Boden and Company Ltd, recounting an inspection of the factory, illustrates the opposition that faced labour reform. It expressed concerns about the impact that prohibiting persons under the age of 18 from night-work would have (on profits, not on the children). It concluded that the children did ‘not appear…to require legislative protection either by reason of the intensity or duration of their labour’. Nevertheless, maximum working hours for women and children were lowered to ten in 1848.

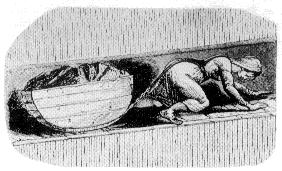

The Chimney Sweepers and Chimneys Regulation Act 1840 prohibited anyone under 21 from sweeping chimneys (by climbing inside). Two years later, the Mines and Collieries Act 1842 was passed, making it illegal for women or any child under the age of ten to work underground in Britain. This was the result of a national investigation into working conditions in mines, which were not covered by the Factories Acts. In the East Midlands, JM Fellows was appointed to interview teachers, miners and their families, colliery owners, and local medical personnel, to assess working practices and the physical and moral well-being of children and young people employed in mines and manufactures.

Pages from “Child labour in the coal mines of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire in the nineteenth century: extracts from the Reports of Commissioners, 1842” by Herbert Green, 1936. (Ref Pamphlet Em. O46 GRE)

Although the doctors regard the children as generally healthy, the children themselves reported tiredness and aches, and sometimes much worse:

No. 133: James Webster

He is just 13 years old and has worked in Newthorpe pits for four years… He worked from six to eight with one hour allowed for dinner…He never works on Sundays. He lives a mile from the pit and gets his breakfast, either porridge or tea or bread and cheese. His dinner is sent, bacon potatoes and pudding with bread and cheese for clocking. He catches it [eats it] as he can by the mouthful. He is often ill-used by the corporals and bigger boys, both with fists, sticks and kicks. Nearly two years ago he was stopping in the bank, when the ass went on, the hook caught him in the eye and cheek and nearly tore it out. His face is much seamed. He was out of work for 12 weeks. Mr Norman was his surgeon, his father paid him and they had not a penny from Barber & Co. The pit is wet and they have to walk in it all day. He is quite tired when he had done a whole day’s work….He had rather work above ground if he got less, it is such hard work. He went to day school a year before he went into the pit. He goes to the Methodist Sunday School at Cotmanhay. He is now in easy lessons. [Cannot spell cat, dog or cow]

All the evidence can be read in ‘Report by J.M. Fellows, Esq., on the employment of children and young persons in the mines and collieries of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire on the state, condition and treatment of such children and young persons’, edited by Ian Winstanley (Ref Em. O42 FEL, or available online).

Initially, little changed. The systems of inspection for all industries were either absent or inadequate, for example the colliery inspector had to give advanced notice of his arrival. The Acts were widely flouted, but growing social awareness paved the way for more successful efforts. It took Master Sweep William Wyer’s conviction for manslaughter in 1875 to finally stop the practice of sending boys up chimneys. George Brewster, Wyer’s 12-year old apprentice, suffocated whilst cleaning the flues at Fulbourn Hospital, and has the dubious distinction of being the last climbing boy to die in such a way in Britain.

Documents relating to social and business history can be viewed in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room. If you are interested in this topic, please see our small display case featuring facsimiles of these and several other documents relating to child labour in the Business Library on Jubilee Campus. Displays are changed twice a year, and usually focus on either business or economic history topics, or on particular business or industry collections we have.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply