October 27, 2018, by Brigitte Nerlich

Climate change metaphors: Crimes, detectives and fingerprints

For quite a few years I have written about metaphors in climate change, such as the metaphors of the greenhouse and the footprint. There is one metaphor I overlooked, and that is the one of the ‘fingerprint’. While the carbon footprint metaphor was used in order to get people to act on climate change, making them aware of how much greenhouse gases they emit and to take responsibility for their emissions, the fingerprint metaphor seems to have been used to talk about the evidence that is accumulating for the fact that greenhouse gases are ‘responsible’ for anthropogenic climate change in the first place.

I was reminded of this when seeing two recent climate change opinion pieces discussed on twitter. One was by Gavin Schmidt, entitled “How scientists cracked the climate change case”, published in the New York Times on 24 October. The article has a wonderful fingerprints illustration/animation, nicely visualising the fingerprint metaphor. The other article was by Andrew Dressler and Daniel Cohan, entitled “We’re scientists. We know the climate’s changing. And we know why”, for the Houston Chronicle published on 22 October. Both articles use the metaphor of the ‘fingerprint’ and of climate scientists as detectives.

This set my metaphor detective whiskers twitching and I rummaged around a bit on both Scopus, for scientific articles on climate change or global warming using the fingerprint metaphor and on Nexis, for media articles doing the same. I’ll first tell you what I found, before coming back to a closer look at the two articles mentioned above.

Tracking the fingerprint metaphor in science and the media

Scientific articles (as recorded in Scopus) seem to have started using the fingerprint metaphor in the early 1990s, that is, around the same time that I found the first fingerprints of the fingerprint metaphor in the media.

In the scientific articles, the word ‘fingerprint’ is sometimes used like an ordinary metaphor at other times like a scientific jargon term, as the following randomly selected headlines show: “Observed and simulated fingerprints of multidecadal climate variability and their contributions to periods of global SST stagnation”, “A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems”, “Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants”, “Record temperature streak bears anthropogenic fingerprint“, “Correlation methods in fingerprint detection studies”, etc….

On Nexis, the first media article using the fingerprint metaphor was published in 1989. The journalist used it in a negative way in a comment on the early work by Bill McKibben, his book The Death of Nature. It appeared in Newsweek and was entitled “The Death of an Illusion” (23 October 1989). The author of the review, Geoffrey Cowley, writes: “When dealing with the causes and consequences of the greenhouse effect, McKibben displays a firm grasp of modern planetary science. Yet his larger theme — that human life is different from the rest of life, and that nature ceases to exist once it bears our fingerprints — reflects a willful ignorance of the same science.”

Cowley argues that nature did not end “when cars and factories started raising the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It ended 2 billion years ago, when photosynthesizing bacteria started polluting the planet with oxygen.”

Here ‘fingerprint’ is still used very loosely to talk about the imprint left by humans on nature.

A couple of years later, in 1991, the metaphor is used in its current form in an article published in The New York Times by William K. Stevens, entitled “Global warming: Search for the signs” (29 January). He points out: “[Climate scientists] are struggling to answer a crucial question: how can a greenhouse warming of the climate be recognized and distinguished from natural warming? They are focusing their detective efforts on various subtle changes that a greenhouse warming would be expected to induce. These signs are known collectively as the greenhouse ‘fingerprint.’”

The article lists a number of ‘fingerprints’ which distinguish greenhouse warming from natural fluctuations in the climate system, such as global temperature patterns, sea surface temperatures, water vapor in the atmosphere, changes in seasonality, rainfall patterns and so on.

After that the use of that metaphor climbed steadily and is now quite ubiquitous (searching for ‘climate change’ and ‘fingerprint’ on Google gives you 3,940,000 results).

The metaphor can, of course, still be used in articles critical of climate science and of climate scientists who are doing the detective work, as for example in this article published in The American Spectator entitled “The Great Hoax”, published at the time of ‘climategate’ on 16 December 2009 (a framing that is still very much with us today). It says under the section heading: “Man-Caused Global Warming Proved False”:

“Even the UN’s own climate models project that if man’s greenhouse gas emissions were causing global warming, there would be a particular pattern of temperature distribution in the atmosphere, which scientists call ‘the fingerprint.’ Temperatures in the troposphere portion of the atmosphere above the tropics would increase with altitude, producing a ‘hotspot’ near the top of the troposphere, about 6 miles above the earth’s surface. Above that, in the stratosphere, there would be cooling. But higher quality temperature data from weather balloons and satellites now show just the opposite: no increasing warming with altitude in the tropical troposphere, but rather a slight cooling, with no hotspot, no fingerprint. Game over. QED.”

The flexible use of a ubiquitous metaphor

So, what about the two articles by Schmidt and Dressler/Cohan, how do they use the metaphor of the fingerprint. At this point I need to point out that this metaphor is actually a metaphor cluster using the whole semantic field of detectives following tracks, finding fingerprints, finding suspects, culprits or criminal, solving a crime and so on. In this context, climate scientists are framed as detectives and indicators for anthropogenic climate change as fingerprints left behind by various suspects, etc.

Schmidt starts his article by pointing to the planet as “the biggest crime science”, indeed he points out that the “biggest crime scene on the planet is the planet”. He talks about the drivers of recent climate trends and how to find out about them: “It comes down to the same kind of detective work that typifies a crime scene investigation, only here we are dealing with a case that encompasses the whole world.” The question is how to find the suspects for this planetary crime: “Scientists have no shortage of suspects for the causes of climate change.” He lists some and says: “Each of these events left a unique fingerprint of change on the climate system […]. To track down the culprit of any one specific climate change involves piecing together the contemporaneous fingerprints and tracking them back to the plausible causes.”

He notes that there “some new suspects too”, mainly linked to human activity. The climatic changes brought about can now be studied with “a new array of tools’ developed by climate scientists working “like forensic detectives”. Using these tools it has become clear that “the current warmth is impossible to explain without human contributions. It is on a par with the likelihood that a DNA match at a crime scene is purely coincidental.” He concludes by saying quite categorically: “The forensics have spoken, and we are to blame.”

Now to the Dressler/Cohan article. They try to explain why scientists are so confident in their assessment that human activities are to blame for climate change and say: “To understand why we are so confident, it’s useful to think about climate change as a whodunit. Climate does not change by itself, so scientists are detectives trying to solve the mystery of what has been warming the Earth for the past century.”

And: “the first thing that scientists do is study these mechanisms to see if they could be the culprit.” They go through various non-human mechanisms that could be the culprits, like the sun and points out: “The Sun, however, has an airtight alibi — we have direct measurements of the output of the Sun from satellites, and we observe that the Sun has not gotten any brighter. One suspect down.” What about the earth’s orbit? “Earth’s orbit changes too slowly and is now in a phase that should be slowly cooling temperatures. Another suspect down.” The same goes for volcanoes. “There is an entire list of suspects that scientists have looked at, and they have not identified a single viable one. With one exception — greenhouse gases.” They then describe greenhouse gases as the world’s dumbest criminal:

“Police shows sometimes feature the ‘world’s dumbest criminal’ — who doesn’t wear gloves, leaves fingerprints all over the house, drops his wallet at the crime scene, is caught on videotape exiting the crime scene, brags to his friends that he committed the crime — and when he is finally arrested has evidence of the crime in his pockets. Carbon dioxide is like the world’s dumbest criminal — it leaves evidence all over the place that it’s guilty.” He concludes by saying “In this whodunit, you would have no choice but to arrest carbon dioxide for warming the planet.”

Both Schmidt and Dressler/Cohan use the detective/fingerprint metaphor but, as we have seen, in very different ways! For example Schmidt uses the word ‘fingerprint’ three times, while Dressler/Cohan use it only one time. Schmidt uses the word ‘forensic’ twice, but Dressler/Cohan don’t use it at all. Dressler/Cohan use the words ‘criminal’ and ‘police’, words that are not used by Schmidt, both articles talk about ‘crime’ etc.

Conclusion

The metaphor cluster associated with the word ‘fingerprint’ has a long tradition. It emerged as soon as climate science became a matter of public debate, at the end of the 1980s. It has become ubiquitous and can be used flexibly and creatively. At a time when evidence and expertise are under threat, it’s a useful and handy metaphor for evidence gathering and for following that evidence to the most logical conclusion.

So, of course, I have to end with a quote from Sherlock Holmes: “You will not apply my precept,” he said, shaking his head. “How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth? We know that he did not come through the door, the window, or the chimney. We also know that he could not have been concealed in the room, as there is no concealment possible. When, then, did he come?” Conan Doyle, The Sign of the Four, ch. 6 (1890)

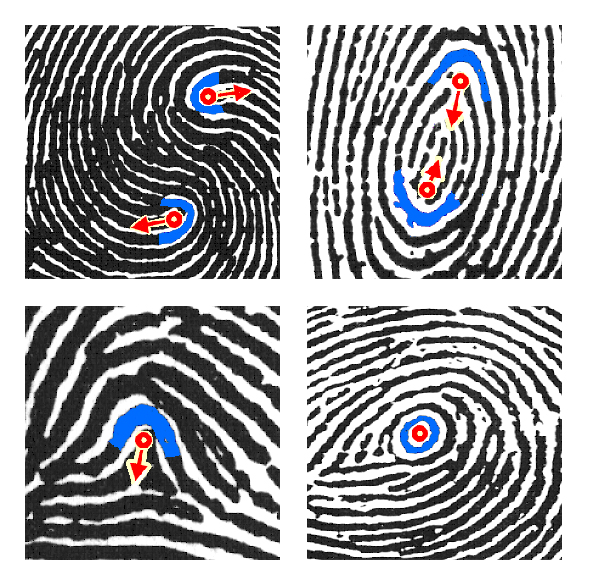

Image: Wikimedia commons

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply