July 22, 2018, by Brigitte Nerlich

Science and trust: Some reflections on the launch of the International Science Council

The Ecologist published an article on 19th July about the launch of a new International Science Council, ISC, entitled “Paris launches the International Science Council with aims to rebuild trust in science”.

ISC is a merger of the “International Social Science Council (ISSC), formed in 1952 to promote the social sciences, including the economic and behavioural sciences” and “the International Council for Sciences (ICSU), formed in 1931 devoted to international cooperation in the advancement of science”.

Reading this article, I was a bit surprised by the many misconceptions of science (and trust) that I found, and which seem to be based on what science and policy experts told the journalist.

Trust in science

Let’s start with the title: “rebuild trust in science”. This implies that trust in science has been destroyed. This is a bold statement. A more nuanced one would have been better. Trust in science has not been ‘destroyed’ overall. So, the ‘rebuilding’ is only necessary for some parts of ‘science’. Some surveys have indeed found a decline in trust – not in science per se though, but in public institutions overall.

Some of reasons why this might be happening are explored in an article by Paul Rosenberg for Salon magazine. The article ends on a note of hope: “Science cannot undo the historical forces at work that have so weakened the bonds of trust, but it can help us respond more effectively. It can help us understand those forces”. To do that, we all – scientists, science communicators, teachers – need to step away from easy memes and clichés that reiterate a ‘deficit model of public trust in science’, as one might call it.

Science, truth and populism

The next sentence underneath the headline says: “Science is humanity’s way of discovering truth. And yet science is increasingly in the crosshairs of populist governments.” Surely, it might have been better to say: And THIS IS WHY science is increasingly in the crosshairs of populist governments.

Later, the new President of the ISC, Professor Daya Reddy, “admits that science cannot ignore public opinion”. I think the opposite is true. Science should not be driven by popular opinion, and, if necessary, should ignore it.

Science and social needs

The article applauds the merger of the two social and natural science councils into one – indeed it sees it as a self-evidently good thing and asks: “What, after all, is science for if it does not fill a social need?” Of course, science can be used to fulfil social needs, but science should never be driven by the imperative to fulfil social needs. As Michael Merrifield and others have recently argued, “true technological innovation often relies on the purest of curiosity-driven science”.

Science, certainty and post-normal science

Then things get a bit complicated. Professor Peter Gluckman is quoted as saying: “Science is not like it once was”. Ok, first of all, science has always been changing; it has never been how it once was. That’s how science rolls. Second, I wonder whether one shouldn’t rather say: the world in which science is done, used and understood is no longer what it once was; and then look at what makes us think that ‘science is not like it once was’ and what that might mean for science and society.

Gluckman continues: “Do you remember rote-learning the periodic table? That was when science was based on certainty. Now science is all about managing and understanding uncertainty.” The article continues by saying: “He calls this post-normal science where certainty is replaced by probability”.

Ok, sciences might have become more probabilistic, but that has nothing to do with the ‘certainty’ with which we once might have believed in or taught the periodic table. That ‘certainty’ is a social phenomenon, not related to certainty and uncertainty in science.

As for science being now post-normal, I rather doubt it. I’d prefer not to use that label, as it is based on a misconception (and a strange dichotomy), namely that science was once ‘certain’ and that it is now uncertain; that values were once unquestioned and now are in conflict etc. (But I bet I have misunderstood all that…)

Gluckman goes on to say: “Take climate change, for instance, where the role of science is to provide clear and unambiguous input to the debate”. Really? Some people might think science is a magic wand. You ask it a question and it gives you an unambiguous answer. But that is not how science works. Science cannot always produce an answer, especially a 100% certain unambiguous answer.

Talking like this creates false expectations about what science can do! As Richard Feynman, yes him, pointed out: “In physics the truth is rarely perfectly clear, and that is certainly universally the case in human affairs. Hence, what is not surrounded by uncertainty cannot be the truth.”

Science, experts and misinformation

Reddy then talks about knowledge management and says that this is no longer “straightforward”, as “global connectivity” has led to “the spread of misinformation and reduced trust in institutions and experts”. Again, this statement needs to be questioned. In my view stating, without corroboration, that trust in institutions and experts is being eroded is itself part of the misinformation that is being spread, and which might erode trust in science and experts.

I have already pointed out above that erosion of trust is not happening for ‘science’ as a whole and a recent study has also shown that this is not the case for ‘experts’ – indeed people trust experts more than politicians. Politicians might want you to think that people have lost trust in experts. But social and natural scientists should perhaps be careful when repeating such opinions.

The end

The article ends with a quote by Professor Cédric Villani: “Politics needs science more than ever – and science has to be at the core of every great project today”. For this aim to be achieved, we have to make sure that we don’t spread misconceptions about science (how it works and what it can do) and about the public appreciation of science.

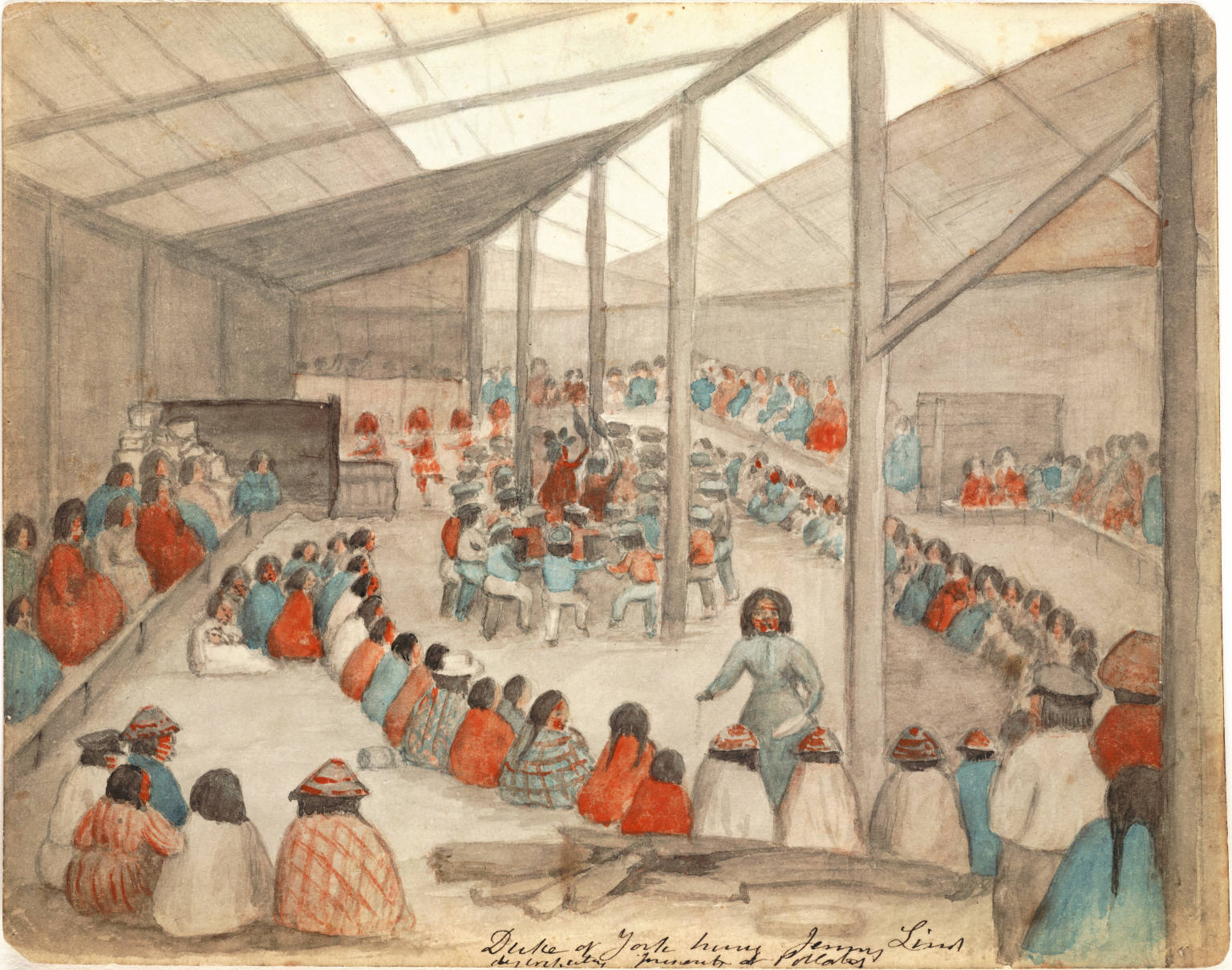

Image: Klallam_people_at_Port_Townsend wikimedia commons

Gluckman is a damn fool.

“Do you remember rote-learning the periodic table? That was when science was based on certainty. Now science is all about managing and understanding uncertainty.” The article continues by saying: “He calls this post-normal science where certainty is replaced by probability”.”

Confusing naming things with understanding them. He wants a list of names. Even when scientists were reduced to listing names and properties there were uncertainties about the properties and the naming was also subject to variation as in biology the tension between cladistics and phylogeny could be considerable so that there was no uniques classification.

It gets worse. Using the example of the study of climate before ~ 1970 about all that could be done with rare exception was data gathering and ordering of the data. With the coming of computers one could actually study the physical and chemical structure of the climate at increasingly deep levels. Gluckman the idiot calls this post normal science

The erosion of trust is linked to the two billion dollars or more that the tobacco and fossil fuel companies have put into eroding that trust

I have to admit that, like you, I was somewhat surprised by these quotes!

Certainty and uncertainty are not the right terms. A better term would be well-defined. An atom/isotope is well-defined. A physical force is a very clear concept. What a high or low pressure area is or a heat wave is a lot more ambiguous.

We do more the latter kind of science now. Personally I find these more interesting sciences, you also have to think about the right concepts to use to make the complicated world comprehensible. It was a reason for me to do something else after studying physics.

Maybe we need a better term for this shift in the kind of problems science studies so that people can more easily stop inappropriately calling it “post-modern”.

Using the term “certainty” may be appropriate in one respect. They say that conservatives like a nice black and white world where things are certain. I can imagine that they thus have a preference for the older sciences.

You are ‘certainly’ right. Certainty and uncertainty are not the right words! But I have to confess I couldn’t quite put my finger on better words. So thanks for suggesting ‘well-defined’. People who are or have been scientists should know that sort of stuff and be more careful with the words they use, I think.

If you can come up with a better term than ‘post-normal’, I’d be grateful for the suggestion. But perhaps we should just say that science hasn’t shifted from the pre? to the post-normal but that, as you say, it is now tackling different problems in different ways?

The ISC is not sending their best …

😉

(To be honest, I have no idea, but likely people who are interesting in such organization are not typical scientists, which they are supposed to represent. A problem that is hard to solve.)

Yes, I would have liked to know more about the merger, why it was seen as important and by whom, what the outcomes are supposed to be etc., and also who now has the ‘power’ in the organisation…