June 22, 2018, by Brigitte Nerlich

Synthetic biology: Modelling joys and fears brick by brick

Carmen McLeod, Stevienna de Saille and I recently published an article in which we used findings from a LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® workshop to show that scientists’ (synthetic biologists’) views of risk and responsibility are much more ‘societal’ than one might expect. This means, involving them in a new form of science governance (RRI), which itself involves new ways of looking at risk and responsibility, can only be successful if social scientists collaborating with them know about these wider views.

In this post I won’t summarise this short article which you can all read yourselves. I will instead focus on one metaphor that is central to synthetic biology and, prompted by the Lego bricks that people used to model and tell their stories, turned out to be quite important for thinking about risk and responsibility in synthetic biology research: building blocks and bricks!

Using bricks to make synthetic biology public

Metaphors and narratives play an crucial role in establishing new fields of science and bringing them to popular attention. In order to construct a public image of synthetic biology as a new type of biology based on engineering principles, some synthetic biologists have used a striking metaphor, namely that of Lego.

It seems to have risen to popularity around 2004, with a first use in the press being attested in the Australian publication Process & Control Engineering: “Synthetic biology: Sets of biological components, DNA cassettes, that are as easy to snap together like Lego building blocks. Assembling genes that direct cells to perform almost any task. Entire organs may be built for transplants.” (January, 2004)

A year later, in an article entitled “Creating life from scratch, one molecule at a time”, the Lego metaphor was used to explain what a new breed of scientists called ‘synthetic biologists’, such as Craig Venter, Jay Keasling, Drew Endy (who used the metaphor a lot alongside Lincoln Logs) and George Church, do: “They’re mixing, matching and stacking DNA’s chemical components like microscopic Lego blocks in an effort to make biologically based computers, medicines and alternative energy sources.” (Associated Press, 18 August, 2005)

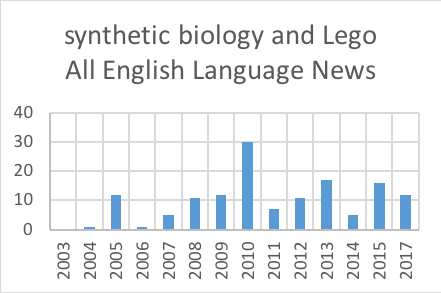

Over the years, the use of the Lego metaphor has waxed and waned in ‘All English Language News’, reaching its zenith in 2010 when Craig Venter announced that he and his team had ‘created artificial life’.

Figure 1: Use of ‘Lego’ in English language news articles on synthetic biology (Nexis®)

The Lego metaphor is supported by other words and images, such as ‘biobricks’, ‘plug and play’, the Lego-shaped trophy that students can win at the International Engineering Machine (iGEM) competition, and much more. It surrounds synthetic biology with “a light-hearted ambiance of entertainment and conviviality”, as Bernadette Bensaude Vincent has pointed out in her contribution to a book examining metaphors in synthetic biology (2015: 94).

Using bricks to think about synthetic biology

This equating of Lego with fun meant that when we first suggested using Lego Serious Play as a method (more detail here) for eliciting views on risk and responsibility in synthetic biology, our proposal was regarded with some scepticism. ‘Serious’ and ‘Lego’ don’t normally go together.

In this post I’ll report on some of models and metaphors created by scientists about science and risk focusing on ‘bricks’. Interestingly, none of the participants in our modelling workshops mentioned the Lego metaphor that is so widely used to talk about synthetic biology itself!

As explained in the EMBO article, we used Lego to elicit participants’ views on risks and responsibilities in the context of their research relating to synthetic biology. As a ‘warm-up’ activity, we asked them to build a model (and tell a story) about why they love science. After that we asked them about risk.

Building blocks of life and building blocks of ideas

Overall, participants loved science because the saw science as a process of discovery and as generating knowledge and understanding. This included conceptualising science as making the world ‘translucent’ and the invisible visible, as discovering ‘building blocks of life’. Participants also saw science as a sometimes difficult but collaborative journey and as permitting various routes and connections.

Alongside these overlapping themes of joint discovery and revelation, the other big theme was science and technology contributing to making the world a better place, overcoming human limitations, but most importantly science being a collaborative enterprise that should not be governed by money, profit and prestige; rather it was envisaged as building bridges and bringing ivory tower ideas down to earth to make them useful.

Two historical figures made their appearance without being named as such: Hobbes and Newton. Science was seen as making an inherently “chaotic, bloody and bad world” amenable to civilisation and life. This better world could come about because, as participants stressed, scientists don’t stand alone but do science by “standing on the shoulders of giants”, by using “the building blocks of previous ideas”.

The joys of science: Bricks, ladders and flowers

In this construction of a relatively idealised picture of science and technology, Lego pieces worked as thinking piece, especially ladders, bricks and shovels (to a lesser extent flags, flowers and the colour green). People used ladders on the one hand to symbolise going up and reaching the unknown through gradual investigation, but they also said that one can use them to climb down and reach people on the ground. Ladders were used to bridge the distance between science and people or between different projects.

Flowers, the results of science, were transported down the ladder in order to reach people. Somebody even built a rope ladder that can be lowered down and argued that it makes it easier for the next person to climb up on. Ladders, i.e. the quest for understanding, could also lead to wonders and serendipitous surprises. In this process the little Lego figures were said to even sometimes find another ladder or build ‘an on-going series of ladders’ – a metaphor similar to that of using building blocks of ideas.

While the acquisition of knowledge and understanding was widely modelled as going upwards on a ladder, some participants also made use of Lego shovels to symbolise that science implied the ‘digging for knowledge’ and some used a Lego torch to symbolise ‘enlightenment’.

Lego bricks in turn were talked about as pieces of knowledge which you can move about and through which you can exchange ideas. Flowers, the results of science, were used to symbolise wonder and pride (“look at this cool thing that I’ve discovered, it’s a space plunger with a flower on it”) or they can symbolise the fruits of science that can be used in the real world.

Overall, science was modelled as a systematic but also serendipitous process of gaining knowledge, brick by brick, ladder by ladder, as a collaborative undertaking, and as a way of making the world a better, more flowery, place.

Risks to science: Black bricks and piles of bricks

Models and representations of risk (in and to science and research) ranged from material risks, to personal and social risks to institutional and systemic risks. I shall focus on some aspects of personal and social risk here which were very much at the forefront of everybody’s mind.

Many participants interpreted ‘risk’ as ‘fear’ and ‘disillusionment’, most importantly fear of failure – of being beating to it, scooped, not getting results (“fishing for results but only getting a little shoe”, “banging my head against the [brick] wall”), not completing a PhD, making a collaborator or, even worse, somebody higher up angry (“sitting on the naughty step”), messing up (“the wheels come off”), feeling lost (“left in the wilderness”), and “digging a hole” for oneself, “digging oneself into the ground” (a different use of the shovel compared to ‘digging for knowledge’) and “getting completely flattened” and “run over”. Even the increased risk of suicide was discussed.

One participant, who brought their own Lego Batman to the session, made a model using mainly black Lego bricks, or as they called it “contraption” of the ‘Black Hole of Doom”. This “represents complete failure, and no PhD, and this is Batman, who’s trying to escape from the Black Hole of Doom, but it’s kind of pulling him in”. There is some hope though, that one might “get past” this stage and then one “sits with the flowers… flowers represent ‘happy’ research – where you want to be, but the Black Hole of Doom is pulling you back”.

One of the most poignant representations of fear, stress and pressure was the following: “so, I think one of the biggest problems I see with science is the lack of co-operation between different scientists, and the pressure that they’re put on. You’ve got two scientists, they’re both working on the same thing, but they’re not talking to each other; their backs are turned to each other, and they both have loads of bricks on their head, because of the amount of pressure that’s put on scientists to produce and publish, and all the rest of it; and you’ve got all the people watching them, waiting for them to publish, so they’re going to start making up results, and lying and things. I think that’s one of the biggest problems we have in science.”

This pressure to generate ‘outputs’ in isolation, visually metaphorised as “loads of bricks on their heads”, is something research leaders and policy makers have to think about quite seriously.

Finally, fears were expressed that the research being carried out might not do what it is hoped to do, namely create alternative fuels and chemicals through gas fermentation. Participants worried about the risk that their research might perpetuate the use of fossil fuels instead.

To represent this risk, participants chose black bricks. While black bricks were mostly used to symbolised death or suicide with relation to personal risks, in this context they symbolise (black) carbon and fossil fuels, which might not be as easily replaced by clean green fuels (represented by flowers) produced through synthetic biology applications as initially hoped.

Conclusion

Models and metaphors are useful for making big science public, as mentioned at the beginning of this article with reference to the Lego brick metaphor used to talk about synthetic biology. Our sessions using Lego Serious play have shown that models metaphors are also useful for talking about science amongst scientists, to reflect on the risks and benefits of carrying out synthetic biology research ‘on the ground’.

Our sessions with aspiring synthetic biologists revealed a sometimes perhaps too rosy image of science (built collaboratively brick by brick), but also some hidden but pervasive fears and worries (symbolised by black bricks and piles of bricks) that are often overlooked when social scientists engage in reflections on social, ethical and legal issues or responsible research and innovation.

When dealing scientifically with ‘the bricks of life’, we should not overlook life scientists’ real joy of building science and a better world; we should also not overlook their real fears of not achieving this when the dark sides of academic performance take over.

Think flowers, not bricks!

Previous Post

Epigenetics and sociology: A critical noteNext Post

Air con and the apocalypseNo comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply