October 5, 2016, by Brigitte Nerlich

Molecular machines

As the BBC reported today: “The 2016 Nobel Prize for Chemistry has been awarded for the development of the world’s smallest machines. Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir Fraser Stoddart and Bernard Feringa will share the 8m kronor (£727,000) prize for the design and synthesis of machines on a molecular scale. They were named at a press conference in Sweden. The machines conceived by today’s laureates are a thousand times thinner than a strand of hair. They could slip inside the human body to deliver drugs from within – for instance, applying pharmaceuticals directly to cancer cells.”

Reading this, I began to reminisce about some research into the visual and cultural construction of nanotechnology that I had carried about a decade ago (inspired by previous work done by Chris Toumey). So I was pleasantly surprised when Roger Eardley-Pryor asked on twitter: ‘Will classic nanobot pics make a comeback with today’s Nobel Prize award for molecular machines?’ The tweet linked to a blog post by Patrick McCray about the 2016 chemistry Nobel and its history, which is a great read. The image illustrating the tweet was of the now classic ‘nano-louse’.

I was even more pleasantly surprised when Philip Ball, who had retweeted Roger’s tweet, recommended that people read something I wrote in 2008 on nano-images. So I thought, I better quickly write a blog post (and this is a really quick one, as I am going to a ‘genome editing’ meeting in London tomorrow).

Science and culture

Let me start by quoting from Patrick’s blog post, which like many other reports on the chemistry Nobel, referred to Richard Feynman’s speculations about ‘nanotechnology’: “How small can you make machinery? This is the question that Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman, famed for his 1950s’ predictions of developments in nanotechnology, posed at the start of a visionary lecture in 1984. Barefoot, and wearing a pink polo top and beige shorts, he turned to the audience and said: ‘Now let us talk about the possibility of making machines with movable parts, which are very tiny.’ He was convinced it was possible to build machines with dimensions on the nanometre scale. These already existed in nature. He gave bacterial flagella as an example, corkscrew-shaped macromole-cules which, when they spin, make bacteria move forward. But could humans – with their gigantic hands – build machines so small that you would need an electron microscope to see them?”

The 1940s and 50s were a time of speculation – with Robert Heinlein publishing his famous short story Waldo (and its miniature mechanical hands) in 1942 (which Feynman might have read). The 1980s, by contrast, were the time when the real work began, now honoured by a Nobel prize for chemistry for Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa- together with the invention of scanning tunnelling microscopes and other scientific and technological nano-breakthroughs.

At the same time as nano fact and fiction began to evolve and get entangled with each other, images and representations of nano- and molecular machines began to take shape. Such images flipped between the natural and the mechanical, the metaphorical and the literal, the fictional and the factional. They also flipped between good and evil, the past and the present and the present and the future. Nano- and molecular machines were imagined as either invading or healing the body, as destroying the world or making it a better place.

It will be interesting to see how current ‘molecular machines’ and their inventors will fare in the world of popular images and imaginations.

Imagining molecular machines

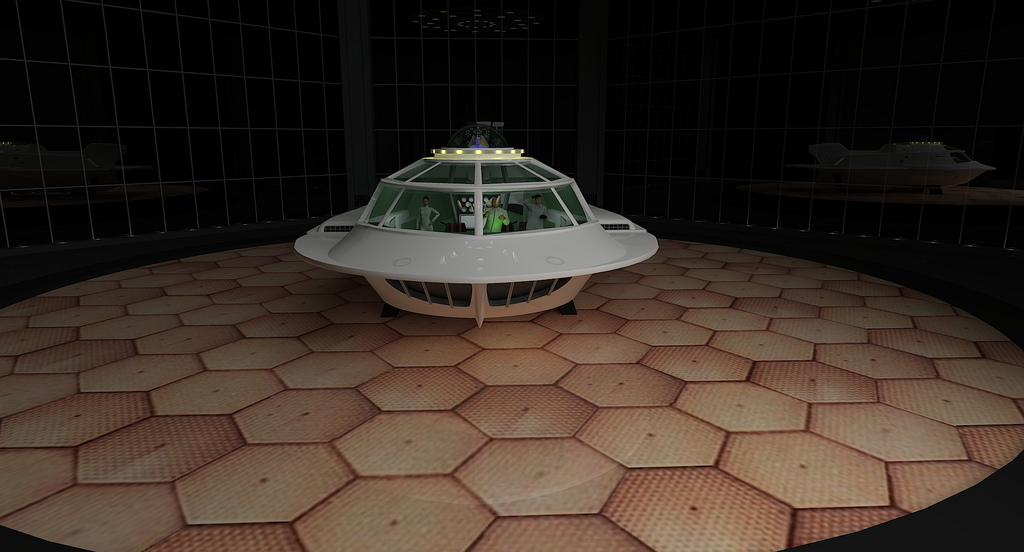

In the past cultural images of nano-machines or molecular machines were inspired by popular literature and films, such as Jules Verne’s novel and its Disney film adaptation Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, whose images in turn inspired the films Fantastic Voyage (1966) (featuring a miniaturised submarine) and Inner Space (1987) (featuring Waldo-type mechanical hands) (see Nerlich, 2005). These in turn (together with ‘real’ developments in nanoscience) inspired numerous children’s books and video games, other films, caricatures, parodies etc. In a third interpretation of Fantastic Voyage, namely Fantastic Voyage: Microcosm (2001) the crew of the Proteus explore the body of a dead alien that crash-lands on earth, and updates the story with such modern concepts as nanotechnology (replacing killer white cells). But we should not forget that some nano-scientists themselves have always told and still tell the tale of nanoscience through the fantastic voyage.

There was a constant give and take between ‘éducation et récreation’ (the motto under which Verne’s novels and their illustrations were published in the 19th century), between fact and fiction and between science and imagination. And long may this last!

If you want to read more about these topics… here are some articles:

From Nautilus to Nanobo(a)ts (2005)

Powered by Imagination (2008)

Nano-bombs and nano-medicine (2012)

Nanotechnology: Social and Cultural Aspects (2015)

Vignette study on nano-medicine/drug delivery (2007)

Of course, I now have to think about all this all over again! Perhaps some of my colleagues might also want to revive this nano images project of which I have very fond memories!

PS Wonderful collection of articles on ‘real’ ‘molecular machines‘ now in Nature

Image: Model of the Proteus Submarine – Fantastic Voyage (labelled for reuse; Flickr)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply