December 5, 2014, by Brigitte Nerlich

Making synthetic biology public: The case of XNAs and XNAzymes

On 1 December a group of scientists at the University of Cambridge led by Dr Philipp Holliger published an article in the journal Nature in which they presented new findings within the field of synthetic biology. Both the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Medical Research Council (MRC), who funded the research, published press releases, and, by 3 December, according to Google News, 21 news items had been published about this research in various outlets. Surprisingly, only three articles appeared in the mainstream press: one in The Independent, one in the Financial Times and one in The Daily Mail. And there is surprise in store for those thinking, ah… The Daily Mail…

On 1 December a group of scientists at the University of Cambridge led by Dr Philipp Holliger published an article in the journal Nature in which they presented new findings within the field of synthetic biology. Both the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and the Medical Research Council (MRC), who funded the research, published press releases, and, by 3 December, according to Google News, 21 news items had been published about this research in various outlets. Surprisingly, only three articles appeared in the mainstream press: one in The Independent, one in the Financial Times and one in The Daily Mail. And there is surprise in store for those thinking, ah… The Daily Mail…

I was actually astonished by how little this announcement was picked up by the press who had lapped up Craig Venter’s advances in synthetic biology about five years ago, and this despite the fact that the Cambridge research seems to be quite exciting. I’ll try to explain why, but, of course, I might get things quite wrong, as I am not a synthetic biologist.

XNA and XNAzymes

Scientists have studied the alphabet of life for quite some time, namely the letters or chemical bases A, T, G, C, letters that stand for adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine. In the 1950s they discovered the structure of the DNA molecule or deoxyribonucleic acid, where pairs of letters or base pairs, attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone, form the so-called building blocks of the double helix. They realised, as my husband puts it, that the book of life has a spiral binding. Since the 1990s scientists have used the letters to ‘read’ entire books of life or genomes, culminating in the reading of the human genome in 2003. Around 2010 they began to ‘write’ new synthetic DNA using these letters or bases. This was the beginning of synthetic biology and Craig Venter’s creation of a synthetic cell.

The exciting thing now is that scientists are able to create entirely new letters or bases, that is, to extend the alphabet of life. Scientists at the Scripps Research Institute accomplished this in work published in May this year. Two years earlier, in 2012 Nature News published an overview fo such research entitled “Chemical biology: DNA’s new alphabet“. Earlier that same year the Cambridge group had demonstrated this ability to extend the alphabet by using nucleic acids called XNA (Xeno nucleic acid), in which the sugars normally present in DNA or RNA had been replaced by other ring structures. The scientists changed the backbone of DNA, meaning that the bases A, T, G, and C, which in DNA are attached to the sugar deoxyribose, are now attached to something else which replaces the sugar. So instead of sugar-phosphate-sugar-phosphate, this polymeric strand now goes ‘something else’-phosphate-‘something else’-phosphate and so on.

Building on this work, the Cambridge team have now shown that XNAs, folded into defined structures, can also act as enzymes which they called ‘XNAzymes’. How was this discovery made public?

Making XNA public

In this post I’ll try to follow the XNA story from the article in Nature through the press release to the stories in the news and see how the story and the language with which the story is told changed and how it is anchored in cultural representations of life and disease, as well as, in this particular instance, potential alien life on other planets. I am following in the footsteps of Jeanne Fahnestock (1998) who studied the ‘rhetorical life of scientific facts’ and examined how the language of science changes in relation to a text’s intended audience, describing the phenomenon as the ‘accommodation’ of science from expert to lay publics.

The Nature article

The article in Nature is entitled Catalysts from synthetic genetic polymers. It reads mainly like this: “We dissected contributions of individual nucleotides in the FR17_6 XNAzyme, defining a 26 nucleotide (nt) catalytic core (FR17_6min). As all four FANA nucleotide phosphoramidites are commercially available, this minimized XNAzyme could be prepared by solid-phase synthesis (see Methods) and was found to retain near full activity (Fig. 2a–c; kobs = 0.026 min−1 at 25 °C), including multiple turnover catalysis (Fig. 2d). FR17_6min shows a pH optimum (pHopt) of 9.25 (Extended Data Fig. 4h), consistent with a mechanism involving deprotonation of the cleavage site-proximal 2′ hydroxyl.”

As one can see, this article is written by scientists in this particular field for scientists in this particular field. Reading through the article as a lay person, a few words jumped out at me that have an ordinary language meaning, but obviously mean something more specific for the scientists, such as ‘catalyst’, ‘scaffold’, and ‘backbone’.

Some of these words were picked up in the press release and the newspapers, as we shall see. The Nature article contained other words, such as ‘cleave’ and ‘ligate’ which were translated in the press release into ‘cutting’ and ‘stitching together’, words which are commonly used by synthetic biologists when they are not writing articles for Nature. Two sentences in the article were elaborated further in the press releases, namely: “implications for the definition of chemical boundary conditions for the emergence of life on Earth and elsewhere in the Universe” and “potential applications ranging from medicine to nanotechnology”.

Press releases

The BBSRC press release announced that “BBSRC funded scientists have created the world’s first enzymes made from artificial genetic material. Their synthetic enzymes, which are made from molecules that do not occur anywhere in nature, are capable of trigging chemical reactions in the lab.” To elaborate further, they refer to the artificial DNA called XNA as ‘building blocks’ (a metaphor translated into a visual image on the Cambridge University announcement of this result). The XNAzymes are said to ‘power’ simple reactions and be able to cut and stitch together small chunks of RNA. (In scientific jargon the phrase ‘building block’ normally refers to individual nucleotides)

The press release quotes three scientists: Dr Holliger, who led the research, points out that the chemical reactions on which life depends are normally ‘kick-started’ (catalysed) by enzymes. He also refers to ‘building blocks of life’ and says that the building blocks created by his team don’t exist in nature but might show that life on other planets could use such ‘unnatural building blocks’. The reference to ‘other planets’ extends the reference the ‘Universe’ in the Nature article. Professor Patrick Maxwell, Chair of the MRC’s Molecular and Cellular Medicine Board, speaks of ‘designer biological parts’ that might be used for therapy or diagnosis in medicine. In terms of applications, the press release expands on the Nature article and points to “new therapies for a range of diseases, including cancers and viral infections”. Nanotechnology is not mentioned.

The MRC press release quotes an additional voice, Dr Alex Taylor, the study’s first author and post-doc at St John’s. He also used the phrase ‘building blocks’ and talks about the possibility of life on other planets.

University news

The University of Cambridge reported on ‘The world’s first artificial enzymes created using synthetic biology’. Again, we hear of ‘building blocks’, of ‘cutting’ and ‘joining’ and of ‘powering’ reactions. Dr Taylor is quoted as saying: “This research shows us that our assumptions about what is required for biological processes – the ‘secret of life’ – may need some further revision.” Dr Holliger refers again to possible “life on other planets” and of these results widening “the possible number of planets that might be able to host life.” ~Again, reference is made to applications – cancer, viral infections, designer biological parts.

Medical and science news outlets

Various medical and science outlets reported on this paper, such as popular science magazine New Scientist, the Bioscience Technology newsletter, The Pharmaletter, and others. Most articles stayed close to the press releases.

New Scientist adds some pieces of information to the emerging news jigsaw puzzle, which are quite interesting: Dr Holliger works at “the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, the same laboratory where the structure of DNA was discovered in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson” (and Rosalind Franklin). The article briefly summarises previous work by Dr Holliger and, without using the ‘backbone’ metaphor, the article makes clear that Holliger’s team replaced the usual ‘sugars’ in this backbone with artificial ones.

Interestingly, New Scientist refers not only to life on other planets, but to ‘exoplanets’, a speculation thrown into the mix by Nobel prize-winner Jack Szostak of Harvard University “who studies the origins of life on Earth”.

As is usual when reporting on scientific ‘advances’, the article uses conventional journey metaphors such as ‘big steps’, ‘major step’. Other mainstream newspapers papers would talk even more conventionally about a ‘breakthrough’ (The Independent, The Daily Mail) and a ‘milestone’ (The Independent).

Mainstream media

The BBC was quick to announce this advance in synthetic biology and used a metaphor that has become quite popular since around 2010, namely making biological entities, in this case enzymes, ‘from scratch’ – meaning basically from nothing. The article too uses the metaphors of ‘building blocks’, ‘cutting’ and ‘joining’ etc, but also says that researchers could ‘jump-start’ simple reactions, similar to the ‘powering’ metaphor used in the press release. The BBC uses one of the rare metaphors used within the Nature article, namely that of the man-made molecular ‘backbone’ but doesn’t explain what it means. XNAs are talked about as ‘hardy’ (the press release had said ‘robust’), as capable to “evade the body’s natural degrading enzymes”, and as “disrupting disease-related RNAs”. Three articles in the mainstream press go beyond these rather sober descriptions.

The Independent

Steve Connor, the Independent’s science correspondent, calls this advance a ‘breakthrough’ and ‘milestone’ in synthetic biology that may enable scientists to cure not only cancer but also “Ebola” and “HIV”. Both are very much in the news at this moment, thus creating nice human interest anchoring points for an abstract scientific news story. The article uses the now familiar words ‘cutting’ and also ‘pasting’; it quotes Professor Maxwell and his reference to ‘designer biological parts’ and Dr Holliger and his reference to other planets and also exoplanets.

Financial Times

Anjana Ahuha, a science commentator, wrote an article for the Financial Times entitled “Artificial ingredients for a primordial soup and recipe for life” that goes beyond this relatively restrained and conventional science reporting. Using the metaphor of a recipe which is well-established in genomic discourse, she links it to the primordial soup and thus the origins of life on earth and elsewhere: “While nobody has yet cooked up a living organism from scratch…the ingredients are coming along nicely.” She speculates about new drugs based on an “alien organism that is immortal”. There is talk about ‘go-faster chemicals’, ‘off-the-shelf synthetic molecules’, and for the first time reference is made to Craig Venter, to his claims of ‘rebooting nature’ as well as to claims about him ‘playing God’. However, there is a proviso: “Controversial though synthetic biology is, it is generally not conducted by chuckling megalomaniacs seeking purely to prove their supremacy over nature” and any “malign intent to manufacture a monster is likely to be thwarted”. Thank God for that!! This article for the FT was not illustrated with an image. However, in a post for the SingularityHub which reports on this latest ‘creation of artificial life’, we find a nice portrait of Frankenstein’s monster!

The Daily Mail

This brings us to the final mainstream media article I’ll discuss here, one published in the Daily Mail. As far as I can make out, this article by Richard Gray, entitled “Do we really need DNA to form life”, is, I think, quite a really good summary of the work by Holliger and his team. It is illustrated not only with a double helix and planets but with some of the original images used in the Nature article. It quotes Holliger, Maxwell and Szostak (‘as quoted in New Scientist’), refers to Holliger’s previous research, talks about ‘building blocks’, ‘cutting’ and ‘stitching’ and quotes Holliger on possible applications – cancer and viral infections. There is also a nicely informative little side box on ‘WHAT WOULD LIFE ON OTHER PLANETS MADE FROM XNA BE LIKE?’ Overall, it stays within the science, does not go over the top and ends with a question, quoting Szostak: “‘But the primordial biopolymer for any form of life must satisfy other constraints as well, such as being something that can be generated by prebiotic chemistry and replicated efficiently. ‘Whether XNA can satisfy these constraints, as well as providing useful functions, remains an open question.’”

The rhetorical life of XNA and XNAzymes

When studying how scientific findings are communicated in popular science magazines, Fahnestock observed a shift from establishing the validity of observations to focusing instead on the ‘wonder’ and ‘application’ of the findings. She also observed attempts to connect findings to publics’ existing values (Fahnestock, 1998, p.334) and cultural stocks of knowledge. Part of this process of ‘accommodating science’ might involve scientists and journalists sensationalising scientific findings in order to attract readers’ attention. As we have seen, this did not happen extensively in the journey I have described here from scientific article to press coverage.

In case of the XNA story we saw that the Nature article is essentially a series of equations interspersed with some words that lay people may understand. Only two of these words were picked up in the press releases, none was really explained: ‘catalyst’ and ‘backbone’. Two words in the article, ‘cleave’ and ‘ligate’, were translated into ‘cut’ and ‘stitch’, thus making the discovery slightly more understandable. ‘Wonder’ and ‘application’ were the focus of the press releases and even more so the press coverage talking about alien life on exoplanets on the one hand and the possibility of curing not only cancer, but also Ebola and HIV.

Framing this research in terms of these currently widely talked about topics connects it to publics’ existing values and interests. Throughout the press coverage, metaphors such as ‘building blocks’, ‘powering’, ‘kickstarting’ or ‘jump-starting’ were used to convey the workings of DNA and enzymes – some more transparent than others. The ‘science is a journey’ metaphor was also used when talking about milestones and major steps having been taken. These are all quite conventional metaphors. The only article that veered into hype and sensationalism was the one published in the Financial Times, especially when it used such old clichés as Craig Venter playing God and ‘chuckling megalomaniacs’ not creating ‘monsters’! The only article that tried to explain the science in some depth without too many rhetorical flourishes was, surprisingly, the one published in The Daily Mail.

[I have written this post partly to contribute to my new work as a social scientist within the BBSRC funded Synthetic Biology Research Centre here at Nottingham; I would like to thank Klaus Winzer for patiently trying to explain synbio and XNA etc. to me, but despite his best efforts, I think there will be some errors in my description!]

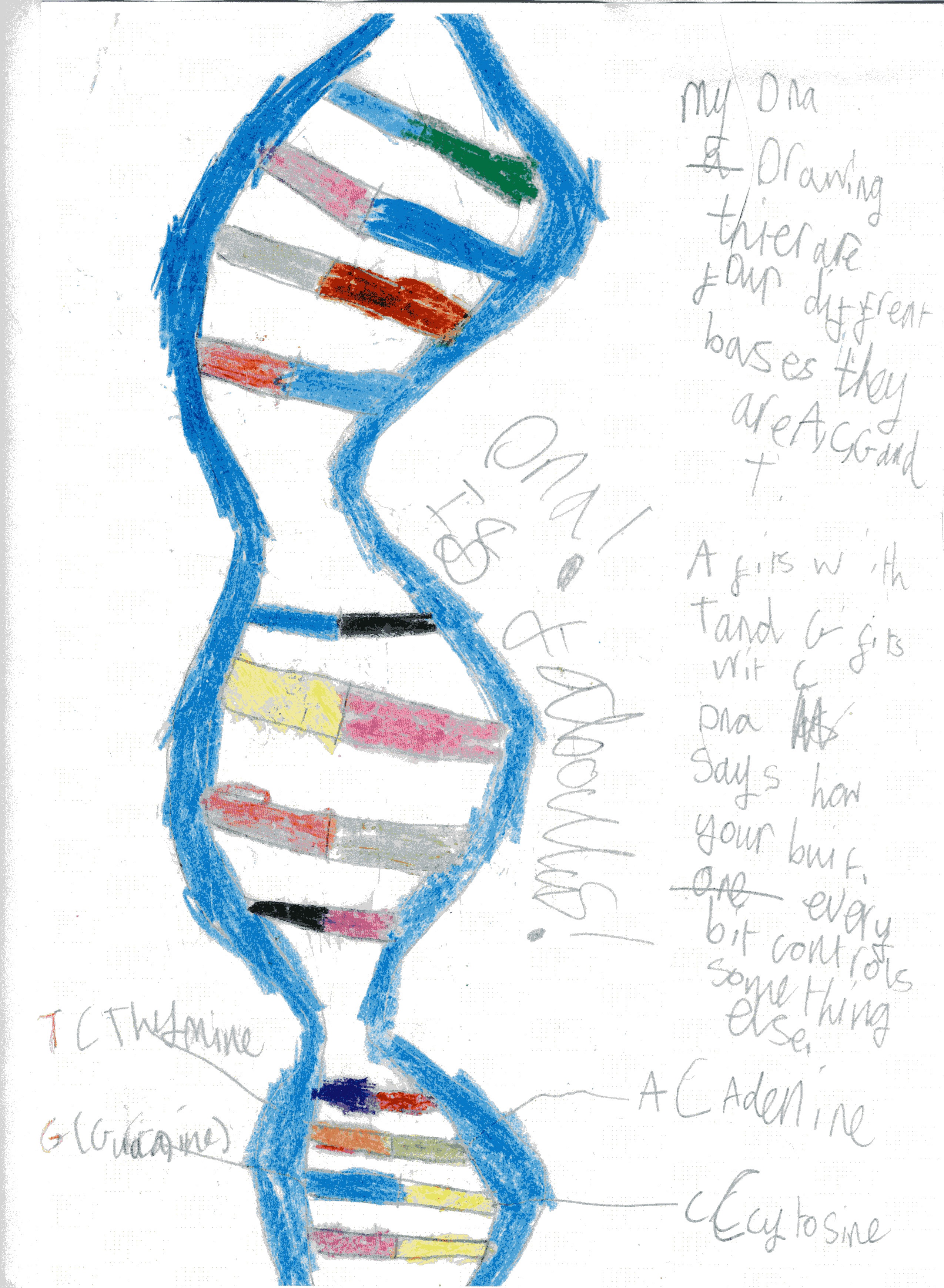

Image: This DNA double helix was drawn by Klaus’s daughter, and, as you can see, it contains more than four different bases 🙂

Interesting to see your comments re the Daily Mail, I’m looking with interest at the Mail’s coverage of synthetic biology and it is suprisingly regular and detailed. It also has significant below the line activity too.

Looking forward to some future analysis 😉

I wonder whether the lack of fanfare about this work comes from the recognition that it’s actually a relatively modest study despite the hype. The “alphabet of life” certainly hasn’t been extended!

In fact the chemical design of enzyme-like catalysts and modification of proteins and nucleic acids to produce interesting properties has been going on for decades – it’s only very recently that this has been wrapped up in the “synthetic biology” package. Nothing particularly wrong with that but one has to be careful not to raise expectations of significance (not to mention useful medical/economic advance!) simply by giving a field a sexy name.

There a couple of things being confused in the articles. The scientists have shown that altering the sugar component of nucleotides or deoxynucleotides results in polymers that can base-pair with RNA (not very surprising) and when the substrate is suitably activated (for ligation) can catalyse ligation and cleavage reactions (also not surprising). But this has little to do with the “alphabet of life”, which as commonly understood, relates to the CGAT of DNA. We already know there are lots of different nucleotides apart from CGAT in living systems as can be seen by inspection of RNA and especially transfer RNAs. The synthesised polynucleic acids with modified sugars can’t substitute for CGAT in living systems so the “alphabet of life” hasn’t been extended at all even if the (rather more prosaic) “alphabet of synthetic nucleic acid-like molecules that can form polymers” has.

And catalysis is a necessary but non-defining property of living systems. One can peruse the scientific literature from the 1970’s and read about the synthesis of polymers with enzyme-like catalytic activity. What a shame they didn’t have the foresight to call their work “synthetic biology”!

As an analogy, if someone synthesises a novel amino acid we don’t say that the range of amino acids in life has been extended. Someone has simply synthesised a new amino acid.

A serious point in all of this is that there is a feeling that we need to start making significant scientific advances in order (it seems) to improve economic competitiveness. There seems to be the notion that we might be able to predict the course of scientific success – we just have to produce impact statements in our grant applications and give our field a sexy name and we’re bound to produce economically beneficial advances. Personally, I think the ideas (which have been around for quite a while) that we can synthesise stuff based on biological molecules and structures using chemical and molecular genetic methods are excellent. However let’s not get carried away by hype!

Thanks for these clarifications. The articles I read were a bit confusing, especially for somebody with no real background in biology – synthetic or otherwise. The alphabet of life analogy was mainly mine I have to confess. I tried to use it to clarify in my head what seemed to be going on there…. But obviously it’s more complicated than that! That’s not soooo worrying. What you say at the end, and rightly so, is perhaps more worrying, namely that (and I have the same feeling) “there is a feeling that we need to start making significant scientific advances in order (it seems) to improve economic competitiveness. There seems to be the notion that we might be able to predict the course of scientific success”. This is where what’s now being called ‘responsible research and innovation’ should kick in, although that concept too, poses perhaps more problems than it’s expected to solve.