June 7, 2014, by Brigitte Nerlich

Describing research in plain language is challenging – but worth it

This is a POST by DAVE FARMER first published on Physicsfocus and which I am reposting here with the permission of the author. Dave is a physics student here at the University of Nottingham. He also participated in our Circling the Square conference and made perceptive contributions from the floor. Dave is an aspiring science communicator and has also been known to study towards a PhD in Polymer Physics when no better distraction presents itself. While his research focuses on probing the elastic properties of polymers at the nano-scale, it is increasing public engagement with science that is his true passion. He loves going out and talking about science and designs and performs live shows, mainly as an excuse to make a mess. Other recent events include the IOP 3 MinuteWonder competition and I’m a Scientist, Get me out of here!, funded by the Wellcome Trust. In this post he talks about the 3 MinuteWonder competition.

***

Three minutes, that’s all we had. Four would have been easy. Three was hard. Just 180 seconds to explain what it is we spend our lives researching, at a level open to all comers. Tough or not, that was the task set to competitors in the IOP’s recent 3 Minute Wonder competition (won by the excellent Hannah Wakeford).

As a rule, we scientists like to wax lyrical about our work, whatever the setting. Indeed, I have often caught myself mid-sentence staring at the glazed eyes and fixed smile of someone who was merely being polite when they asked what I did twenty minutes earlier. The fact is, I’m unashamedly passionate about physics. If someone asks about it, I’m going to tell them. I’d rather tend towards this extreme than the mysterious “I’m a scientist”, which contains very little real information about what I do. But how do you fit everything you want to tell people in to three minutes? The answer soon became clear to me. You can’t. And that’s where it got interesting.

As a PhD student, I’ve spent the past three years of my life trying to become exceedingly knowledgeable within a very small area. It’s my job to care, even obsess, about the smallest details. Those details are important to me, but frankly, very few other people in the world are interested. Don’t misunderstand me, I believe my work has worth – maybe even ‘impact’ (but let’s not go there). It is not, however, what could be called ‘general interest’.

I suspect it would be easy to find many PhD students who, freely or otherwise, would admit this. To be honest, for our day-to-day lives, it doesn’t matter what the general population think. But this is why 3 Minute Wonder was so interesting. Now, instead of thinking ‘What do I want to tell them?’, it became, ‘What do I NEED to tell them so they understand?’.

When we think of stripping down research into its essentials, we often resort to using technical language. That is what it is there for after all, to reduce complex topics into linguistically digestible nuggets. The nature of 3 Minute Wonder, however, precludes the use of any technical language that you can’t explain to the layman in the time limit. Tricky.

You see, we live bilingual lives as scientists: one language for our colleagues and one for non-scientific acquaintances. Bridging this language gap effectively is key to any successful outreach project. The interesting challenge here was translating research into plain English without losing the precision of the technical language. This is what I came up with:

“I hit things with a stick and watch them wobble.”

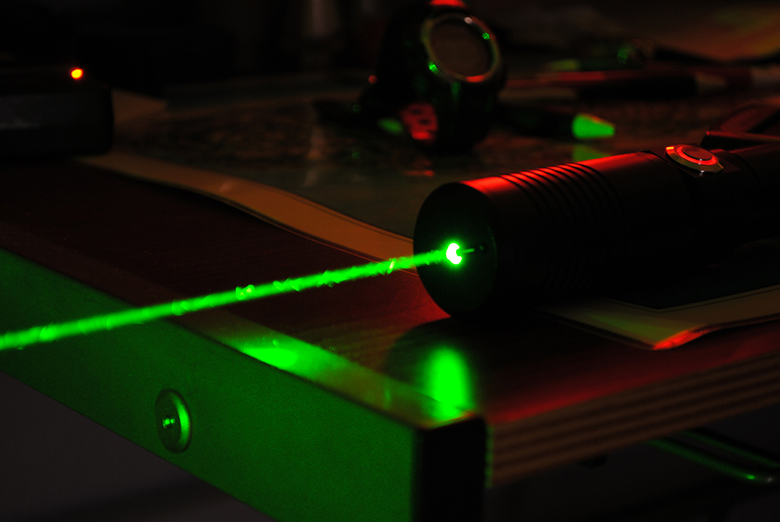

OK, my work isn’t quite that simple. The things I hit are very small and the stick is actually a laser. That phrase does, however, capture the essence of it. The feelings this forced simplification elicited in me were both disheartening (‘Is that really all I do?’) and cathartic (‘Huh, maybe this PhD lark isn’t so complicated after all!’). More than that though, it gave me the rare chance to step back and consider my work in a wider context.

I don’t mean a ‘wider context’ as we often see it in academia in the token conclusion to a paper: “This work is also potentially applicable to neutron stars etc…”. I’m thinking of a much wider context. The next time someone asks what I do, I have a better answer than either just “I’m a scientist” or an excruciatingly detailed physics lesson. Public engagement, or outreach, is, after all, a key criterion for ‘impact’ (damn, said I wouldn’t go there…). What better place to start than by actually letting the ‘general public’, such as it exists, know what we do on a down-to-earth level in normal conversation?

The simplification imposed by a three-minute time limit, while worthwhile, is not common. Our default method of communicating our work – academic papers – rightly allows us to indulge in the detail. We do this in our own scientific language. Being forced to simplify my own work, however, made me consider: why do we almost exclusively use complex language in academic literature? There are certainly many cases where technical language simplifies and improves communication but I wonder if it has become self-indulgent.

Why do I write in an academic report that “a mechanical impulse was applied to oscillate a droplet” when in fact I just hit the lab bench near it to make it vibrate? I suspect that the simple fact is that: this is what peers and journals expect; this is how we’re taught. We all need to publish, so we go along with it. Perhaps a distinction needs to be made between technical language, which is often necessary, and jargon – a word with negative connotations.

In the example I gave above, the simpler explanation actually contains more information than the jargon version. An argument could be made that the ‘jargonized’ version focuses on the key point that the droplet was wobbled. Crucially, however, for someone trying to replicate the experiment, they have a much better idea of what was done when the language is simplified, which can only be a good thing. It also has the nice side-effect of being understandable to someone not versed in our technical language.

I’m not advocating the removal of all technical language and detail from publications, or suggesting that all papers should be written for a lay audience. The issue we have is that by immersing ourselves in this language, it is often very easy to lose sight of the simple specifics of what we do. This is damaging to our efforts to communicate with both the public and with other scientists.

Which brings us back to 3 Minute Wonder.

The combination of having to step back and paint your work in broad strokes while at the same time using precise, clear, non-technical language is a fascinating challenge. It’s one that I’ve learnt a lot from and is, to me, a clear example of how stepping outside your comfort zone to communicate your science can feedback into the everyday, creative process of research in a positive way.

Give it a go. But be quick about it.

Image: A laser. (Not a stick.) Credit: Andrew ‘FastLizard4′ Adams, reproduced under a Creative Commons licence.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply