August 3, 2015, by Blog Administrator

Malaysia’s Higher Education Blueprint 2015-2025 – the implementation challenge

In early April, Malaysia announced its Higher Education Blueprint 2015-2025 – a bold statement of how the country’s higher education sector would be transformed over the coming decade. It builds on and complements the Education Blueprint launched in 2013 which in turn had been designed to transform the schooling system. The focus of the Education Blueprint was improving teacher quality, reducing administrative burdens, broadening access, and reforming curriculum and assessment in order to propel Malaysia to a position in the top one-third of countries global in PISA and TIMS by 2025. Together these two documents signal a desire for major and transformative change in education. And both are clearly needed.

Malaysia has invested heavily in its education sector. Currently the Federal Government devotes in excess of 20% of its expenditure to education at all levels – a higher proportion than that observed in many high income countries. In higher education, specifically, the latest “Universitas21 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems” places Malaysia 12th in the world in terms of the resources committed to higher education and in the top 3 in the world if the level of economic development is taken into account.

But all of the evidence would suggest that this investment is not generating the return that Government and society might have expected. A recently announced study by the OECD[1] provides a global ranking of the performance of school systems around the world, drawing on the OECD’s own PISA tests, the US-based TIMSS assessment and Latin America’s TERCE system. The test scores reported for Malaysian secondary school students were disappointing and the country ranked 52nd out of 76 countries in the analysis. In contrast, Asian neighbours, Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan occupied the top 5 places in the league table.

The picture at tertiary level is more mixed. Malaysian Universities have not performed well in global rankings and currently there is only one Malaysian University in the QS World top 200 (although there are 6 in the Asian top 200). No Malaysian University makes it to the top 200 into either the Shanghai Jiaotong Ranking or the THE Rankings (although the two leading Malaysian Universities declined to participate in the latter).

Of course, the limitations of these global ranking exercises are well known and by other metrics, Malaysian higher education has made significant progress. Access to higher education has improved significantly with substantial growth in enrolment, particularly at Masters level. The Blueprint reports a 70% increase in higher education enrolments over the past 10 years to the current level of 1.2m. And the quantity and quality of research has grown with a 3-fold increase in publications 2005-12 and a 4-fold increase in citations (2005-12). Some 70% of these publications come from the 5 “research universities” and reflect the outcomes of a highly selective approach to research support.

While there is much to celebrate in terms of higher education performance indicators, a number of significant concerns remain. Graduate employability is highly variable across institutions but the average figure 6 months after graduation is around the somewhat disappointing level of 75% and employers regularly comment on the lack of critical thinking among graduates, poor communication skills and weaknesses in terms of softer skills. A 2013 survey by Grant Thornton reported that 62% of employers in Malaysia were concerned about their ability to recruit staff with the right skills and 48% believed that a major constraint on growth was access to talent.[2] The apparent failures of higher education to deliver a workforce that meets the country’s needs is of particular significance given the ambitious plans for growth outlined in the 11th Malaysia Plan.

In 1991 Malaysia launched its vision to become a high income developed nation by 2020 as part of the 6th Malaysia Plan. The recently launched 11th Malaysia Plan outlines what is necessary to finally realise this vision. It targets 5-6% annual growth in the economy based on domestic and external demand; it promises a 7.9% rise in gross national income per capita and substantial expansion in private investment. These targets are widely seen as challenging and bold. Their delivery will depend upon a major shift in the economy with reduced dependence on the simple increase in either labour or capital productivity. Growth in GDP will be underpinned by a significant increase in multi-factor productivity which relects the impact on output of a combined set of inputs rather than individual inouts in isolation. The increase in multi-factor productivity is expected to contribute 40% of the planned growth in GDP[3]. Although Malaysia’s economic growth has been strong and consistent with the overall target for 2020, labour productivity on its own has been disappointing and stands at a little over half of that observed in South Korea. Key to the success of the 11th Malaysia Plan is a need for people-centric growth. For higher education this means switching the emphasis from quantity of provision to quality of provision from the simple acquisition of knowledge to the development of a broader range of personal transferable skills (what are often described as higher order thinking skills or HOTS).

Alongside the concern that HE is not delivering the workforce that the economy needs, a further concern that influences current debates is the overall system performance and return on investment. As previously mentioned, the U21 Ranking of National Higher Educations highlights the significant investment that has gone into HE, but it also foregrounds the country’s relatively low ranking in terms of outputs (dominantly research outputs but also measures of enrolment). In the latest U21 rankings published in May 2015, Malaysia ranks 12th of it expenditure on higher education but only 44th for its outputs (all unadjusted for level of growth). In the growth adjusted figures to picture remains similar with Malaysia ranking 3rd for its financial investment but only 34th for its outputs.

At the risk of plagiarising the infamous speech by Tony Blair in 1997, if Malaysia is to realise the growth in productivity that is necessary for the country to sustainably be a high income nation, its priorities must be “Education, Education, Education”. Is the Higher Education Blueprint up to the challenge?

The Higher Education Blueprint is a substantial document – running to well over 100 pages in its large format published version. The product of extensive consultation (the Blueprint lists over 10,000 participants in consultations), it was launched on April 7th in a high profile event attended by some 1500 people in central Kuala Lumpur.

In numbers, the Blueprint proclaims its intention to build on 5 system-wide aspirations and 6 student specific aspirations which are to be delivered through 10 shifts in policy and practice which will in turn, be implemented over 3 waves of activity.

Structurally there is a strong and compelling logic to the Blueprint. The system-wide aspirations outlined in the primary and secondary-focused Education Blueprint (2013-2025) all come with clearly specified targets. These feed through into system wide aspirations for the higher education sector and the primary targets are shown below.

As well as system level aspirations, the Higher Education Blueprint identifies 6 “Student Aspirations” – what student can expect to receive from higher education. These emphasise the notion of balance – between Akhlak (ethics and morality) and Ilmu (skills and knowledge), suggesting a switch from a pure talent creation remit to something rather broader and reflective of a citizenship as well as a human capital agenda.

Delivery of both student and system aspirations relies on 10 shifts that are at the heart of the Blueprint and these comprise both target outcomes and Malaysia-specific and policy-driven enablers.

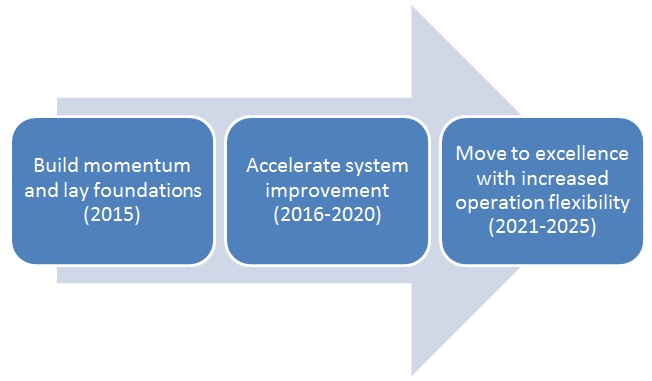

An implementation roadmap identifies three waves of activity to realize the proposed shifts.

So far, so good. And indeed, across the sector, many of the proposed changes have been welcomed, but invariably the question of implementation comes up in conversation. Indeed, even at the launch, the Prime Minister, paraphrased Tony Blair to stress to the audience that “it’s all about the execution, execution, execution”[4].

Morshidi Sirat (former Director General at the Ministry of Education) and CD Wan have expressed similar concerns[5].in their recent commentary on the Blueprint. They point to the relative brevity of the Roadmap and the absence of a detailed action plan. The latter is slated to be provided by the Putrajaya Higher Education Delivery Task Force giving rise to additional concerns that the outcome will be more rather than less complexity and bureaucracy within the system.

More fundamentally they argue that the Blueprint lacks an underlying philosophy; the “soul” of this ambitious document has not been clearly articulated, they say, and, as a consequence, they argue that there has been no overarching debate about its foundational principles. They suggest an underlying neo-liberal agenda, but a qualified one given the emphasis on balance (akhlak and ilmu) and the changed use of language – from “human capital” in the earlier strategic plan to “talent” in the Blueprint.

The neo-liberal critique has been amplified in discussion at a recent forum hosted by the Strategic Information and Research Development Centre[6]. A range of speakers from the public and private sectors in Malaysia highlighted expressed concern about the under-pinning market-driven agenda and the absence of any debate about the “public good” characteristics of higher education. And of course there was reference to the issue of academic freedom and government interference in the academic discourse, especially in public universities.

How serious are these criticisms? The charge of neo-liberalism is nothing new – either in Malaysia or indeed many other HE systems. At one level, the commitment to maintain the level of spending per student in public institutions suggests that there is significant commitment to the “public good” dimensions of higher education. And, of course, the current high standing of Malaysia’s HE system in terms of resource inputs is, in part, a product of the development of a significant private HE sector. Indeed the internationalization of Malaysian higher education owes much to the efforts of the private sector and while there continue to be many challenges relating to its management and regulation, its contribution to the sector is substantial, providing over 45% of HE enrollments. But the real concerns of those voicing the neo-liberal critique are perhaps more focused on the use of market mechanisms and market based agendas – encouraging competition, students as consumers, and HE in the service of business and industry. And these are all in evidence in the Blueprint. The pragmatist in me would suggest that these elements are not fundamental problems in themselves. Market mechanisms can and do have a role to play and the real challenge is perhaps not their presence or absence but how they are managed and regulated.

This brings us back to the implementation critique and it is here that the challenges are arguably greatest. Morshidi Sirat and CD Wan have already drawn these to our attention. And quite rightly so. The vision that underpins the Blueprint is one of transformational change. Its realization will require more than just changes in policy; it will require a more fundamental cultural and attitudinal change within the system – a willingness to let go of traditionally models of working, a withdrawal from relatively hierarchical command and control mechanisms, a move to more collaborative working with the academy and a more trust and risk-based approach to the relationship between the Ministry and those involved in delivery. The bold vision outlined in the Blueprint should be welcomed but policy makers will need to be even bolder if it is to be implemented successfully. The content of the Blueprint itself is testament to a recognition of the need for change if Malaysian HE is to perform on an Asian and on a world stage. Public statements and private discussions confirm that sector leaders are convinced of the need for reform. But delivery will require large-scale organizational change across a complex sector and herein lies the challenge.

[1] Sean Coughlan, Asia tops biggest global school rankings, 13 May 2015, available at http://www.bbc.com/news/business-32608772

[2] See for example http://news.asiaone.com/news/malaysia/najib-puts-focus-raising-productivity#sthash.z9oLOIWb.dpuf.

[3] See http://news.asiaone.com/news/malaysia/najib-puts-focus-raising-productivity#sthash.z9oLOIWb.dpuf

[4] See http://malaysiandigest.com/news/548939-najib-launches-malaysia-education-blueprint-higher-education.html

[5] Morshidi Sirat and CD Wan (2015) “Success of blueprint depends on buy-in and politics” University World News, 05 June, Issue No:370 http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=2015060214590283

[6] See http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2015/06/27/varsities-that-only-turn-out-worker-bees/

Christine Ennew is Professor of Marketing at the Nottingham University Business School, UK, Pro Vice-Chancellor and Provost of the University of Nottingham, Malaysia Campus. She sits on the OBHE Advisory Board. Previously, she was Director of the Division of Business and Management in Malaysia and Director of the Christel de Haan Tourism and Travel Research Institute – follow her on Twitter @ChrisEnnew

The post Malaysia’s Higher Education Blueprint 2015-2025 – the implementation challenge appeared first on OBHE on 23rd July 2015.

Thanks for sharing.

http://www.fairessays.com/about

You’re welcome! 🙂