November 1, 2018, by Benjamin Thorpe

Reading group: South-South transnationalisms

- Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective (2018) “Manifesto: Networks of Decolonization in Asia and Africa”, Radical History Review 131:176-182; also published on Medium: https://medium.com/afro-asian-visions/a-manifesto-by-the-afro-asian-networks-research-collective-30857823579f

- Laura Bier (2010) “Feminism, Solidarity, and Identity in the Age of Bandung: Third World Women in the Egyptian Women’s Press”, in Christopher J. Lee (ed), Making a World after Empire: The Bandung Moment and its Political Afterlives (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press), pp. 143-172

- Tomoko Akami (2017) “Imperial polities, intercolonialism, and the shaping of global governing norms: public health expert networks in Asia and the League of Nations Health Organization, 1908-37” Journal of Global History 12:4-25

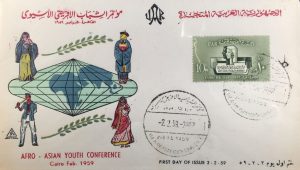

We began the first reading group of the new academic year with a set of texts inspired by the Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective’s recent “Manifesto” on the study of transnationalism in the global South. Along with the manifesto itself, we looked at two examples of studying such networks, covering different time periods, though each was oriented around a Bandung: Tomoko Akami’s analysis of ‘intercolonial’ networks, centred around the 1937 Intergovernmental Conference of Far-Eastern Countries on Rural Hygiene in Bandung, and Laura Bier’s paper on transnationalism in the Egyptian women’s press in the era of the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung.

Grouping these readings under the rubric of ‘South-South transnationalisms’ invites a number of thorny questions over terminology that run through all three papers. The Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective confront this in the first few words of their manifesto, when instead of speaking vaguely of the South, they use the term ‘Third World’. By doing so, they mean to follow the example of Vijay Prashad [1] and reclaim the original intent behind the term, which in the 50s and 60s was meant as a project, a radical political force which ‘sought communication and solidarity across difference’.

This reclamation of a radical subaltern voice chimes with their more general insistence that we look toward internationalisms whose centre of gravity is not located in the West, and whose participants are not only the state-sponsored political elite, but a wider array of non-state actors as well as society at large. This urge is most clear in their insistence that we look beyond Bandung: that instead of allowing the 1955 Bandung conference to function as synecdoche for – and thereby overshadow – Third World transnationalism, we instead ‘acknowledge the larger Afro-Asian environment in which the “Bandung moment” took place’ (177).

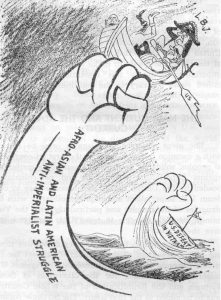

Miao Ti, “One Wave Higher Than The Last” (1966). From “The First Afro-Asian-Latin American Peoples’ Solidarity Conference”, Peking Review #4 (21 Jan. 1966), pp. 19-25, 20

This approach is shared by Laura Bier, whose chapter on transnational feminist solidarity in Eqyptian women’s magazines is cited by the Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective as an example of work they would like to see more of. Bier’s period is not defined by Bandung, but by Nasser, from the 1952 Egyptian revolution that brought him to power to his death in 1970. Bandung is by no means absent from Bier’s account, but she argues, like the Manifesto, that it needs to be appreciated as more than just a diplomatic event; rather, it ‘had social and cultural repercussions that serve to bridge the complex history between imperial discourses of womanhood to the contemporary politics of global feminism’ (144). While the familiar Western-oriented story is one of internationalist feminism suffering a lull after WWII before recovering in the 1970s, the story Bier tells is of transnational solidarities and linkages being vividly expressed in the Egyptian women’s press of the 1950s and 60s. Bier brilliantly shows how these linkages sometimes worked to radically assert transnational solidarity under the banner of ‘sisterhood’, while sometimes – often at the same time – reinforcing notions of the essential alterity of these ‘other women’.

Tomoko Akami’s paper shares this twin urge to on one hand expand our conception of internationalism beyond the West, and on the other hand expand our conception of South-South transnationalism beyond Bandung ’55. She does so by examining the forms this transnationalism took in the interwar period, before the invention of the ‘Third World’ (as a term or project). Though Akami accepts the League of Nations’ central role, she explores an understudied aspect to League-affiliated institutions and events, which she terms ‘intercolonialism’. Her focus is on the activities of the League of Nations Health Organisation, particularly its 1937 ‘Far Eastern Rural Hygiene Conference’ in Bandung. This lens expands academic attention on the League’s relationship with the colonial beyond Susan Pedersen’s work on the Mandates [2], to encompass the much more numerous raft of territories outside Europe that had not been possessed by the defeated powers of the First World War, and that had to fit into the League’s form of internationalism in some other way. Meanwhile, Akami’s focus on the intercolonial allows her to go beyond the traditional political dichotomy between national and international politics. She shows this to be a myopic framing that has served to blind us (that is, Western scholars) to the complexities of how transnationalism functioned outside the West.

This point returns us to a deeper and more troubling aspect of the Afro-Asian Networks Research Collective’s Manifesto: their demand that scholars of transnationalism open themselves to radical new research methodologies. They look squarely at the geography of scholarship on the transnational, and demand that it too embrace the transnationalism of its object of study, and by doing so recognise ‘the need for collaborative history in approaching decolonisation from the point of view of the Global South’ (177). Such an endeavour would replace the ‘lone scholar’ model with one of collaboration, and would place a premium on transnational and translingual research. (On this point, they express important reservations about the geopolitics of archival digitisation projects.) Perhaps most knotty is the challenge to overcome Western scholars’ positionality, as the Collective themselves readily admit to their own compromised position as ‘scholars based at Euro-American universities [who] are implicated in the privileges of the current system even as we look to readjust its inequalities and limitations’ (177). These are all difficult challenges to get to grips with, but as a set of open questions that provoke us to consider our own research practices in a new light, their urgency and importance could not be clearer.

[1] Vijay Prashad (2007) The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World, series edited by Howard Zinn (New York & London: The New Press)

[2] Susan Pedersen (2015) The Guardians: the League of Nations and the crisis of empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply