June 17, 2016, by Harry Cocks

King Hugh of Italy (c.885-948): Success and Failure

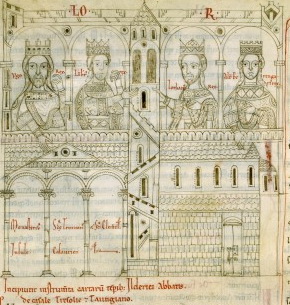

In his Antapodosis (‘Book of Revenge’, c. 960) the Italian bishop Liutprand of Cremona (d. c. 972) discussed the career of Hugh of Arles who had been the king of Italy between c.885 and 948 (pictured, left, in the twelfth-century chronicle of Johannes Berardi). It was his particular concern to cast a negative light on “the many virtues of King Hugh that lust undermined.” Comparing Hugh’s virtue with his many sins of the flesh, he noted that, to his credit, “King Hugh was of no lesser wisdom than boldness, nor of smaller strength than craftiness, also a worshipper of God and a lover of those who love holy religion, solicitous for the needs of the poor, very caring towards churches; he not only loved but also deeply honoured religious and philosophical men.” However, Hugh was also a man “who even if he shone with virtues, besmirched them through his passion for women.” Chronicles like that of Liutprand are often seen as the necessary tactics of those who sought places under Hugh’s successors Berengar of Ivrea and Berengar II. Taking this into account, historians have tended to judge Hugh’s reign kindly, as effective and energetic. However, in a new article for Early Medieval Europe, Ross Balzaretti argues that perhaps the “narratives of failure,” produced by clerical writers like Liutprand, Rather of Verona, Flodoard of Reims, and (later) Hrotswitha of Gandersheim were in fact more accurate and more powerful than modern scholarship has suggested, and even helped to undermine Hugh’s rule and bring it into disrepute.

Hugh’s morals were at issue in these accounts mainly because his rule could only have been possible because he had adopted a very broad concept of “family” (he was a bigamist, had seven illegitimate children and two legitimate ones) to secure a wide, but at the same time personal network of supporters. Liutprand sneered at Hugh’s four wives, five concubines and nine mostly bastard children, but he must have known that sexual relationships of such kinds were the very stuff of successful kingship in his day. The evidence of petitions shows that Hugh’s royal largesse was bestowed largely on his own family as an important means of enabling his rule.

Balzaretti argues that these negative judgements weren’t simply careerism on part of the writers hoping for preferment in the aftermath of Hugh’s reign. Instead they were political interventions in themselves that helped to destroy Hugh’s reputation for justice, causing him to lose the support of the local aristocracy by portraying him as a “Provençal” interloper, highlighting the illegitimacy of most of his children, and ruining his posthumous reputation into the bargain. Such stories, even when penned by apparently interested parties, contained telling power.

“Narratives of Success and Narratives of Failure: Representations of the Career of King Hugh of Italy (c. 885-948)”, Early Medieval Europe 24, 2 (2016): 185-208.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/emed.12140/abstract

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply