May 5, 2015, by Harry Cocks

The Man-Eating Wolves of Renaissance Italy

In 1516, the town of Varese Ligure in north-eastern Italy experienced an “invasion of wolves.” Antonio Cesena (b. 1507), a local canon and historian, recorded in his Relatio dell’origine et successi della Terra di Varese (c 1550s) that “a great fear arose about wolves [that] began a new and unaccustomed war, not against herds and flocks as normal, but against human flesh.” At that time, Cesena reported, even “brave and courageous men refused to go about by themselves or unarmed,” while a famously brave local bandit was said to have been eaten by the ferocious beasts. Wolves not only “besieged the roads” and attacked sheep but also took a child from its anguished parents. “Every day one heard shouts and screams,” Cesena said, while all were alert with weapons and dogs. Three of his own friends and relations were attacked by wolves, one bitten on the face and another on the head. Many locals believed that the animals were a sign of lycanthrophy, the process by which men turned into wolves, often, it was thought, through the effects of melancholy. However, Cesena and other educated writers dismissed such tales as “beyond any doubt untrue,” although they recognised that certain cases had been recorded in the distant past by the Roman naturalist Pliny. Wolves did not only enter the centre of Varese, but also, during plague outbreaks of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, fed on half buried human remains and attacked those too fatigued by illness or starvation to defend themselves. At that time, Cesena said, a child was decapitated by a wolf.

Cesena’s account is corroborated by several others. Another wolf incursion in Taggia at other end of Liguria was recorded around this time and many municipalities around Genoa gave rewards for the capture of wolves. Records of lupine incursions in the region date back to 1324 when wolves were said to have got as far as the harbour at Genoa, where they stole bread and provisions from boats.

Wolves came right into the middle even of cities such as Milan, where in 1528 wolves “attacked and ate people during the night, entering their homes and even during the day they consumed whoever they could.” They were also reported to have dug up bodies in cemeteries. This was common feature of rural life even well into the eighteenth century. For Cesena, the wolf invasion was not only a frightening contact with wild animals, but also a “prodigy of many bad things.”

Cesena’s account is described in a new article for Rural History by Nottingham CAS fellow Robert Hearn, Charles Watkins of Nottingham Geography and Ross Balzaretti of Nottingham’s History Department (see link below). The authors (who also discussed Ligurian wild boars in a recent piece – see Blog 17 July 2014) show that Cesena’s Relatio is not only an account of these human-animal interactions, but also a valuable record of changes in landscape. Cesena distinguished typical land uses, what he called “known and domestic” from “wild and uncultivated.” This way of seeing nature was part of a wider set of oppositions in his work that saw the cultural world of humans as the binary opposite of the natural world of animals. In that “wild” landscape beyond the reach of humans, bears, wolves, and boar roamed. However, wolves were given the most attention in the Relatio as “bold, gross, raw, wild and thieving animals.” In that sense, the authors suggest, the wolves represent the boundary in Cesena’s work between domestic/cultured and wild/natural. In this way the real hungry animal was transformed into the symbolic beast of history and myth.

ROBERT HEARN, ROSS BALZARETTI and CHARLES WATKINS, “The Wolf in the Landscape: Antonio Cesena and Attitudes to Wolves in Sixteenth-Century Liguria”

Rural History / Volume 26 / Issue 01 / April 2015, pp 1 – 16

DOI: 10.1017/S0956793314000193, Published online: 09 March 2015

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0956793314000193

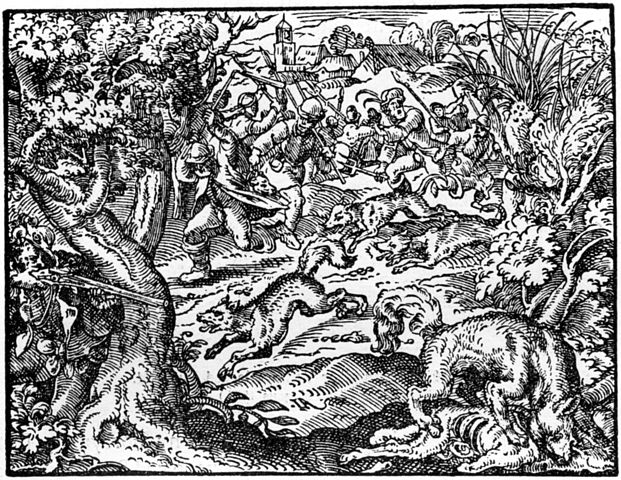

Illustration top right: a wolfhunt from, Neuw Jag vnnd Weyderwerck Buch, Frankfurt am Main 1582

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply